Type and Heart Disease

"If you're trying to avoid cardiovascular disease, a pear-shaped figure is better than a beach-ball body, according to research from the University of G3teborg, Sweden.", read a recent news article. (Reader's Digest, June 85, p. 169) It reported the work of Ulf Smith and his colleagues who made hip and waist measurements on 3,000 people, and found that the distribution of fat predicted heart attacks more precisely than weight alone. The pear-shaped figure is our old friend the endomorph, while the beach ball figure is the endomorphic mesomorph.

This study can be compared with others dealing with android or deep body obesity vs. gynoid obesity in which scientists propose that fat cells in the abdominal area are more active in releasing fatty acids, and therefore in posing a risk of heart disease. Their observations are another link in a long chain of evidence that stretches back to Hippocrates and his apoplectic type.

James Mitchner recounts a conversation he had with the famous cardiologist Paul Dudley White who had supervised Eisenhower's 1955 heart attack. White had listed eight factors predictive of heart disease. They had included heredity, blood pressure, cigarette smoking, etc., but also body build. He was leery about excessive claims in this area, but asserted, "...if you classify a thousand deaths from heart failure, you find that very few strike ectomorphs, not too many hit endomorphs, but a heavy predominance knock down mesomorphs." (New York Time Magazine, Aug. 19, 1984, p. 77) He described Mitchner as an archetypal mesomorph who was barrel-chested and heavy across the heart and rump.

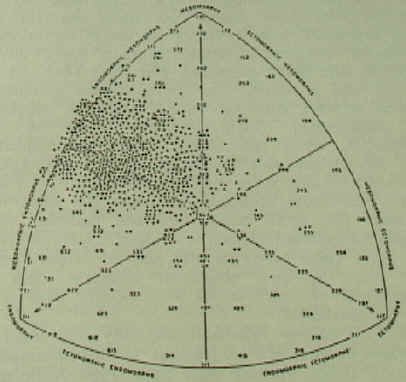

Fig. 12. Coronary Heart Disease Somatotypes.

Dupertuis and Dupertuis.

Sheldon had remarked on the endomorphic-mesomorphic qualities of victims of heart disease, but it was his colleagues C. Wesley Dupertuis and Helen S. Dupertuis who made an extensive examination of this whole issue in a study that focused on who survived longer among cardiac patients in The Role of Somatotype in Survivorship Among Cardiac Patients. The Dupertuises eventually examined almost 2,000 individuals, and it was a portion of this larger group who became the subjects for their study on the length of survival. Using Sheldon's trunk index method of somatotyping, they compared somatotype photos of 118 deceased patients who had survived more than five years with 82 patients who had died 5 years or less, and then examined another 319 people who had also survived 5 or more years. They found that the long term and short term survivors did not differ in socioeconomic background, height, weight, heart disease patterns, and blood pressures. But what they did differ on was physique. The heart disease patients in general differed from the normal American population in somatotype. Their mean somatotype was 4.1-4.5-2.1, while the normal American somatotype was 3.3-4.1-3.4. But somatotype also distinguished between the long term and the short term survivors. There were more mesomorphs among the short term survivors and more endomorphs and balanced endomorphs-mesomorphs among the long term survivors. The short term survivors also showed larger dysplasias. There is, then, consistent evidence about the somatotypes of heart attack victims, but what about their personalities?

In 1974 Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman inaugurated a new era of interest in the personalities of heart attack victims with their Type A Behavior and Your Heart. Earlier an upholsterer, repairing the chairs in their office, had remarked that the chairs were in great shape except for their front edges, but the import of this comment had escaped them. Gradually, though, they began to compile a portrait of the Type A personality, starting with the traits of excessive competitive drive and a chronic sense of time urgency. Their portrait of the coronary prone personality grew until it included competitiveness, aggressiveness, love of action, explosive accentuation of speech and laughter, excessive energy for action, rapid eating, guilt about relaxation, limited introversion, leadership in a competitive situation, a total commitment to the job at hand, a chronic sense of time urgency, haste, impatience, hyperalertness, the doing of multiple jobs simultaneously, and the inability to relate to things or people not job-related. They found that serum cholesterol levels could vary directly with the intensity of Type A behavior, and in a study of over 3,500 men it was the presence of Type A behavior that was the most powerful predictor of who was to come down with coronary heart disease. They saw the Type A personality engaged in a chronic struggle which triggered the hypothalmus to signal the sympathetic nervous system to secrete large amounts of epinephrine and norepinephrine.

By now we have become too familiar with Sheldon's mesomorph not to recognize him in the Type A personality, especially since we have already been alerted by the somatotype studies of coronary patients. What Friedman and Rosenman are doing is rediscovering part of Sheldon's temperament descriptions from the point of view of cardiologists, but they are not aware that they are doing it, which, in some ways, makes it all the more interesting. They had an inevitable but passing knowledge of somatotypes: "If you were to sit in the reception room of a busy cardiologist for several afternoons and observe his patients, you would not be struck by their obesity. While it is possible that one or two out of thirty to fifty persons were a bit roly-poly, few of them would appear to be downright fat. Well-nourished, yes; perhaps a bit on the burly side; but not grossly overweight. You also would probably not see a single, quite tall (over six feet), very lean or almost gaunt individual." (p. 159) But it never occurred to them that these different body types had been carefully related to their corresponding temperaments. This is both good and bad. It's good because it allows us to compare their independent descriptions of the endomorphic mesomorph to Sheldon's in which we read: assertiveness of posture and movement, competitive aggressiveness, physical courage for combat, the unrestrained voice, horizontal mental cleavage, and so forth. There can be no real doubt that Friedman and Rosenman are describing the mesomorphic temperament when it becomes excessive and overdeveloped, and so these two sets of descriptions confirm each other.

But on the negative side, the proponents of Type A personality are creating a specialized fragment of a typology without realizing that it could gain in strength by being integrated into a larger framework. They are finding, for example, Type A behavior among children, which brings to mind the many studies on the temperament of children like Walker's, or the classification of babies as suckers, kickers, and watchers. Recently there has been a disturbing trend in Type A research in which a number of research studies have failed to find a relationship between the Type A personality and heart disease. Ray Rosenman is quoted as saying that Type A behavior "may not necessarily be bad for any given individual at all", and other researchers have found that fast-paced speech and eating, and a sense of time urgency did not appear to increase the risk of heart disease. What is happening? It seems reasonable to suppose that the initial Type A description was an amalgam of normal temperamental traits, and their excessive development. It is entirely normal to be a mesomorph, and so many of the mesomorphic traits will not only not be found to be directly predictive of heart disease, but they will be connected with high achievement. But this should not be taken to mean there is no Type A personality in the sense of a particular kind of imbalanced mesomorphic personality that is at risk for heart disease. Type A description has to become more refined by being able to separate the underlying temperament from its distorted development.

In Treating Type A Behavior - and Your Heart, Meyer Friedman and Diane Ulmer describe a study of 800 men who had already suffered heart attacks and were divided into two groups. The first received normal cardiological counseling and the second received Type A behavior counseling. The second group suffered only one third of the number of subsequent heart attacks of the first group. Friedman and Ulmer go on to describe a program by which the Type A personality can modify his behavior, and their advice is not simply medical, but humanistic in the best sense of the term. They want the Type A personality to broaden his range of interests, to take a deeper interest in the lives of other people, to interest himself more in art, literature and religion, and to be more demonstrative in showing affection. And again, our typological point of view allows us to read these recommendations from a special perspective. If the coronary prone personality is an endomorphic mesomorph with a predominantly mesomorphic temperament, then the extraverted thinking psychological type should predominate, and therefore, the question of the modification of the Type A personality can be seen against the larger backdrop of the process of individuation that the extraverted thinking personality is called to. Is it outlandish to imagine that Jungian analysts or Jungian-oriented counselors could work with coronary prone people? They would be aware both of the extraverted thinking drive of these personalities, as well as their undeveloped feeling function. If they were to read a case study of a Type A personality in conflict with his family in which "he often blurts out cutting, hurtful remarks", (p. 93) this would not be strange to them at all. Or if they hear of the Type A's attraction to "affectionate puppies and nondesigning children" (p. 219), or the difficulty they have in "the verbal expression of love - or at least of human love, for he can love and freely receive the love of various animal pets. A strange paradox." (p. 36) they will see those traits as reflections of the state of the feeling function. If the Type A personality were to be brought into the Jungian perspective, then the whole range of analytic techniques could be brought to bear on the problem.

Sparacino reviews a variety of studies on the effectiveness of various ways of measuring Type A behavior. And it is interesting to note in light of our discussions of the ways to measure temperament that the standard interview technique has become the norm against which the other instruments are evaluated.

In the Dupertuis study of the survival of cardiac patients, the short term survivors were described as being "more apprehensive about their illness, more reluctant to accept any limitations in their physical expression or their role as head of the household and breadwinner, and more opposed to any show of sympathy or protectiveness by other members of the family. It appeared also that the short-term survivors as a group exhibited a persona that was more outgoing, aggressive, energetic and restless than was true for the long-term survivors. The latter group seemed more able to accept their 'fate' and appeared to be more relaxed and willing to adapt to the situation in which they found themselves." (1968, p. 96)

What is emerging, then, is the description of the coronary-prone patient at the level of somatotype and temperament, and the possibility that it could be extended to psychological type. What we would need to complete our program of an integrated typology in this area would be a biochemical profile of the victim of heart disease. And in the last few years this, too, has begun to emerge. Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein, for example, have identified mutations in a gene involved in the premature onset of arterial sclerosis which causes a defect in the person's ability to remove low density lipoproteins. Other gene defects have been found which hinder the body's ability to create high density lipoproteins. But what are the normal levels of high density and low density lipoproteins among the endomorphic mesomorphs from which most heart attack victims come?

The parallelism between the somatotype based description and that of the coronary prone personality which, as far as we know, developed independently of each other, is too striking to be ignored. It illustrates the possibility of using typological language as a basic framework within which to place biochemical, genetic, social factors, etc. It also suggests the possibility of using Jung's model of the individuation process to find ways to modify the behavior of Type A personalities. The differentiation between long and short term survivors in what first appears to be a rather homogenous group of cardiac patients is strikingly similar to the differentiation we have noted in the Delinquent Youth series, and could be interpreted in the same fashion, i.e., that underlying the somatotype distribution are two distinct psychological type territories.

Type and I.Q.

"In 1858, 20-year-old Paul Morphy of Louisiana toured England and France, routed every known chess giant of the day and then returned home to live the rest of his life in seclusion." ("Introverts at Play", P. 72) This is how Ralph Olmo and George Stevens begin their report on the psychological type of chess masters, which they determined by giving the MBTI. They found that 17 of the 19 high-level players were introverted, and intuitives outnumbered the sensation types by 2 to 1. Surprisingly, they found no difference between thinking and feeling, though this result might be an artifact of the test itself.

I.Q. is a lot like mesomorphy, in fact, it's treated often like a mental mesomorphy, a quality we never can get enough of, and should have more of than other people. But if mesomorphy is a more or less unitary notion, it's hard to say the same about I.Q. From a typological perspective we would expect that each type would have a particular kind of intelligence, and if we were to administer the same test to different types, some types would excel more than others. Far from this meaning that they are more intelligent, it simply means the test is measuring a kind of intelligence that is closer to the kind they possess. We have already seen how the 2-2-5 somatotype and the introverted intuitive psychological type excel in academic performance. Part of the reason resides in their particular kind of intellectual gift, and part, as Sheldon suggested, lies in environmental factors such as the fact that they are not distracted by social life or tempted to devote their energy to athletics.

In the Myers-Briggs Manual we find this following salutary caution as a preface to their reporting of the results of type and I.Q.: "In examining the data that follow, it is important to keep in mind that academic aptitude tests are designed primarily to measure knowledge and aptitude in the IN (introversion, intuition) domain; there are many other interests and capabilities that aptitude tests are not designed to measure. It is unfortunate that aptitude tests are often interpreted as being equivalent to measures of intelligence. Their scope is more limited." (1985, p. 96)

We are far from getting a clear picture of what these different kinds of intelligence mean, and how to weigh the components of innate ability and environment. There is an element of natural ability. The psychological types of the chess champions are no more surprising than the fact that the somatotypes of the marathon runners are different than that of the discus throwers or the shot putters. The real danger is that we will exalt one particular kind of intelligence, just like we have idealized mesomorphy. The fact that I.Q. appears typologically conditioned gives us a particular way in which we can read about the I.Q. controversies. For example, much has been made over the difference in I.Q.s between blacks and whites, and more recently over the fact that Orientals have I.Q. scores that are about as much above the Americans as the American whites are above the American blacks. Does this mean that the Japanese are smarter than the Americans, or the American whites are smarter than the American blacks? The usual response has been to point out the vastly different environmental conditions for each group, and this should be the primary answer. But it's also possible to look at this issue typologically. If different types perform differently on I.Q. tests, then if there are different frequencies of types in different populations, the I.Q.s of the groups would tend to differ slightly. The Japanese are probably more introverted as a whole than Americans, and they could easily possess more people of those types that do well on I.Q. tests. The same could easily be true between American blacks and whites. If we factored out the differences due to environment, the small differences remaining might easily be explained by the differences in typological frequencies. But we really should go further. If I.Q.s differ with type, and the evidence both from the point of view of somatotype and psychological type indicate that they do, then the notion of comparing people by I.Q. doesn't make much sense. If we line up a group of children and make them compete in the 100 yard dash, some will excel, and as the study of professional athletes has shown, these people have a certain kind of somatotype. But there is no way we can say that the children who excel are better than the children who do not in anything but running the 100 yard dash. There are differences, but we can't extrapolate from them to justify various social and political causes. This is a perennial temptation. It appeared, for example, in a virulent form in the eugenics movement of the first decades of this century in the U.S. There are human differences, and these differences will become more and more evident as our knowledge of biochemistry and genetics increases. But the real issue is not that human differences exist, but how we are going to handle them. We can't deny their existence, but we can't succumb to the temptation to justify various social programs on the meager knowledge we now possess.

On a more personal note I.Q.s seem rather pointless, a kind of tyranny of numbers. Our own children have never been tested, and we see no point in doing so. One would undoubtedly score higher than the other, but what would it prove? Simply that they had different kinds of intelligence, and there is no evidence that in life as a whole one kind is better than another. Each of us has a great deal of unused mental capacity, and this is where the emphasis should be, not whether one person is somehow smarter than another. The diversity of gifts that does exist is meant to serve the community, but instead, we often let it degenerate into mindless competition. This is one of the areas where Jung's work in psychological types holds great promise for the future.

Type and Gender

Beyond the obvious physical differences between men and women there are general somatotype differences. If we compare populations of men and women on the somatotype charts, men are distributed more widely, and women are less mesomorphic and more endomorphic. It's as if men are more experimental beings. Therefore, we could expect to see both a higher incidence of certain gifts and a higher incidence of certain defects, and there is evidence for both.

The distribution of women's somatotypes poses several problems for typology. It's harder to tell women apart on the basis of somatotype. The differences that separate one type from another are smaller, and it is also harder to decide how to divide the woman somatotype sample since the center has shifted more towards the endomorphic pole of the somatotype chart.

There are also differences in the distribution of the different psychological types between men and women. Jung noted some of these differences in passing in Psychological Types. When speaking of the extraverted thinking type, he says:

"In my experience this type is found chiefly among Men, since, in general, thinking tends more often to be a dominant function in men than in women. When thinking dominates in a woman it is usually associated with a predominantly intuitive cast of mind." (p. 351)

And when speaking of the extraverted feeling type he comments:

"As feeling is undeniably a more obvious characteristic of feminine psychology than thinking, the most pronounced feeling types are to be found among women." (p. 356)

He also feels that the majority of the extraverted sensation types are men (p. 363) and that the extraverted intuitive type is more common among women (p. 369). Finally, he writes:

"It is principally among women that I have found the predominance of introverted feeling." (p. 388)

Our own experience bears out Jung's when it is a question of thinking and feeling, but we have not noticed any differences in the frequency of sensation and intuition. Summed up in its simplest form men with primary or secondary feeling or women with primary or secondary thinking are not common, to say the least. We take special notice when we meet one, and there is a real difference between a woman using her third function of thinking, a woman who is in the grip of the animus, and a woman whose thinking is typologically higher than her feeling. The same differences exist among men. This kind of development of thinking in a woman or feeling in a man is rare enough to cause special kinds of adjustment problems because of the expectations that society has. This area has gotten scarce attention, and among the different typological preferences, thinking and feeling are probably the most environmentally conditioned, making progress in this area more difficult. For example, when a new version of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator was created, the only major adjustment was in the area of thinking and feeling. Before, the distribution among males had been 60% thinking and 40% feeling, and among females, 1/3 thinking and 2/3 feeling. In a 1972 study of university of Florida freshmen, there were only 44% thinking among males and 28% among females. The scales, therefore, had to be adjusted to match the old figures, but if the scales were that environmentally conditioned, we are certainly allowed to wonder whether the initial estimation of thinking and feeling and their different scoring for men and women were also environmentally conditioned. In short, it would not be surprising if there were a lot less thinking women and feeling men than the MBTI indicates.

The possibility remains, then, that the specially constructed and adjusted scales of the MBTI which, incidentally, differ more than the other scales when compared with the Grey-Wheelwright (MBTI Manual 1985, p. 209), are weighted more to produce thinkers among women and feelers among men. "On the TF (thinking- feeling) scale, it was evident that females, even those who in their behavior and attitudes indicated a clear preference for thinking, had a greater tendency to give certain feeling responses than did males. The difference was ascribed either to the possibility that certain feeling responses were more socially desirable for females than males, or to the effect of social training." (p. 149) But what if it were not environmental reasons but innate typological reasons that produced these tendencies?

One further note. Long before we knew anything about somatotypes we met some women who typologically appeared to be intuition thinking types, and they had a distinctive body type, a sort of husky build with a great deal of ectomorphy, as well. This brings to mind Jung's intuitive cast to thinking women.

The differences between the sexes in somatotypes and psychological types should eventually be brought into relationship with recent studies in sex differences in cognition and lateralization. For example, boys tend to score higher on tests of spatial ability and girls on tests of verbal abilities. These spacial abilities include maze performance, various exercises in mental rotation and chess. Bradshaw and Nettleton in their Human Cerebral Asymmetry surmised the list might also include musical composition and mathematics (p. 215). On the other hand, women are "less susceptible to language-related disorders such as developmental dysphasia, developmental dyslexia, stuttering and infantile autism." (p. 216)

There is a certain amount of evidence that sug6gests that females are less lateralized than males and therefore show less deficits after left hemisphere traumas. If the greater lateralization of males is confirmed, it would be an internal counterpart to Sheldon's observation of the wider distribution and more experimental nature of the male somatotypes. One would suspect, as well, that the psychological types of males not only differ in frequency of type from females, but might be more extreme within the particular type. In other words, women would show more balance in the use of the various functions while men would be more exclusively one-sided. Whether this is true or not, or whether any analysis has been made or could be made of psychological type test data, I don't know.

Sheldon also indicated that the ectomorph was one of nature's most extreme experiments, and so we could expect to find both a higher incidence of these particular spatial-oriented gifts as well as developmental problems. As usual, both somatotype and psychological type are ignored in most of these studies. There are, however, several clues that point in this direction. Early maturing adolescents perform better on tests of verbal ability, and late-maturing adolescents score better on spatial ability. And since boys develop later than girls, it is suggested that "the prolonged maturation typical of males would ultimately lead to greater lateralization, greater separation of function and spatial (but not verbal) superiority, and a greater opportunity for language malfunction to occur." (Human Cerebral Asymmetry, p. 223) But as we will see in the studies on the maturation of the different somatotypes, it is the ectomorph who is the late maturer. This can be connected with studies of male rats outperforming female rats in mazes. There is also evidence "that females who are high and males who are low in the male sex hormone (androgen) score higher on spatial ability tests." (p. 218) And what males would be low in androgen if not those dwelling at the opposite poles of mesomorphy in the ectomorphic regions? From a psychological type viewpoint would Jung's women with thinking with an intuitive cast or women who are extraverted intuiters show higher androgen levels, higher spatial abilities, and more difficulties in traditional gender roles?