|

Online

Transcript:

The words endomorph, mesomorph and ectomorph have entered

into our language as ways to describe different kinds of human bodies, but we don’t

realize that they are the fragments of one of the greatest adventures in the history of

American psychology and were coined by one of its giants, who less than twenty years after

his death is almost completely forgotten.

Our story beings here in Pawtuxet, Rhode Island where William Sheldon was born in 1898

in a house that dated back to the 1740s. His grandmother’s diary reads:

"Saturday, November 19th… Heavy rain. Will and Mame have a baby boy

born at 25 minutes of six in the afternoon."

His mother and father came from old New England stock and though the family wealth was

gone, their poverty did not weigh heavily upon them, for they could draw on a bounteous

nature, a love of learning, and a sense of their place in the scheme of things.

Sheldon had an archetypal American boyhood. The family had a half acre garden of corn

and tomatoes, carrots, peas and potatoes, and his father was an avid fisherman and hunter

who supplemented his income by shooting game birds for market. Sheldon later called him

"a lover of the wild and a reader of books," and watched him raise Irish setters

and fine poultry. He was a shooting champion of national stature, and a founder of the

Pawtuxet Gun Club. And little William grew up hunting rabbits and squirrels for the pot,

gathering black walnuts and chestnuts, and fishing and claming.

Sheldon was on intimate terms with the inhabitants of the woods and marshes. He would

play with the earth worms in his garden and look at the great moths who were a special

love of his mother as almost part of the family. He would watch sympathetically and

protectively as the great blue crab molted and entered into its vulnerable soft-shelled

stage. It was a life attuned to the rhythms of nature, but for all that it did not lack a

sense of culture and refinement, and a deep sense of belonging. There was his oldest

brother Israel and his sister Kate, and his friends at the local school, and the world of

the little village of Pawtuxet with its summer afternoon picnics, and the snows of winter.

As a child of 5 or 6, during an excursion to the Boston Marathon, William had been taken

by his Aunt Mary to visit her old friend, William James.

And all over the pre-revolutionary war homestead where he grew up he saw the evidence

of where he had come from.

On the night of June 10th, 1772 Christopher Sheldon had joined 8 rowboats

full of Providence men who made their way with muffled oars to his majesty’s ship

Gaspee, sent to enforce the stamp act, and burned her.

Pardon Sheldon had commanded the ship Hanover out of Providence on a voyage through the

Baltic Sea.

And his grandfather Israel Remington Sheldon had served as an officer in the war

between the states. His commanding officer in the Rhode Island Artillery wrote commending

him: "Campe near Falmouth, Virginia, February 7, 1863. Lieutenant Israel R. Sheldon

has been engaged in many battles, always in command of a section, and by earnest endeavor

through the whole time of his service fairly entitled himself to promotion."

Sheldon’s visual gifts and powers of observation were honed from his earliest

years. He grew up in a world where observation was not a form of idle curiosity, but the

means of putting food on the table or money in the pocket. It was a world where men prided

themselves on their ability to shoot a duck flashing overhead, and to judge a fine hen or

dog. And William took it for granted that it was possible for trained observers to come to

virtually identical conclusions, for he saw it happen over and over again at dog and

poultry and cattle shows. Sheldon became a fine shot and amateur ornithologist, and early

on had a growing reputation as an appraiser of early American cents. All these things were

to serve him well when he found his life work in trying to scientifically describe the

differences among human bodies and temperaments and how the two were interrelated.

But the warmth of this New England world which was soon to be swallowed up in an

increasingly urbanized America became his benchmark against which to measure his feelings

for everything else, and most everything else failed to measure up. Later he would dream

of the long winter evenings about the open fire when chores were done and there were

chestnuts, apples and sweet potatoes for roasting, and the popping corn and parching corn

and cider. "All these," he writes, "were part of the regular harvest of the

countryside and so were taken for granted, like the logs in the fireplace and one’s

parents. There was one thing, however, which retained at all time such a halo of mystery

and enchantment that it never came to be taken for granted. This was the cigar box of old

copper cents which my father kept locked up in the grandfather sea chest… On evenings

when he was feeling especially well disposed, the kitchen lamp would be meticulously

trimmed, the red kitchen tablecloth would be cleared of debris and brushed, and out would

come the magnifying glass, four or five well-thumbed coin books, and the cigar box with

the big cents."

Sheldon graduated from Warwick High School in 1915 and entered Brown University. With

the American entrance into World War I he was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in

a machine gun company, and in 1919 received his degree in absentia. After the war he

wandered westward, and it was sometime during these early years that Sheldon discovered

the age-old riddle of the relationship between physique and temperament. He took a Ph.D.

in psychology at the University of Chicago, writing a dissertation under the direction of

L.L. Thurstone on the correlations between bodily measurements and mental traits.

In a series of studies Sheldon did, indeed, find a relationship, as others had done

before him, but it was a small one and he could find no way to bring it out more strongly.

He was 30 years old and had the makings of a good academic career. All he had to do was

reconcile himself to the limits of the methods he was using. But he sensed there was a

deeper dimension to this body and temperament riddle if only he could find a way to get at

it. It was at this point that he made a fateful decision that was to bear enormously

interesting results and embroil him in bitter controversy. What would happen, he asked

himself, if he really looked at these bodily and temperamental differences? Could a

carefully cultivated sense of clinical observation give him a way to break the impasse?

Sheldon decided to fit himself for such an experiment by going to medical school and

carefully studying the work of one of the world’s leading typologists, Ernst

Kretschmer.

Sheldon took thousands of standardized photos of college men, but instead of letting

measurement dominate the hunt, he scrutinized them, looking for basic factors that could

be found in different degrees in all human bodies. Toward the end of his life he was

interviewed on public television and described the basic elements that he discovered.

Dorothy Paschal: Dr. Sheldon, can you explain why we have to have a somatotype

photograph?

Sheldon: Well, I’ll try. A photograph is necessary if you want to really observe

the proportions and shape of a structure and have that all before you, not just depend

upon simple measurements. Actually, a human somatotype is really a way of describing he

shape of a body Somatotype simply means body type, or the shape and form of the body. Now,

if you really want to visualize the shape and form of something, a picture is a little

better than words. It picks it up a little faster. So we base the whole early work of

somatotyping on the process of photographing many thousands of different growing boys and

girls, and college students and adults, and later in various patterns of physical

variation as seen in medical school, in several hospitals where I have worked, and finally

standardized the somatotyping procedure on the photographic process.

Dr. Paschal: Would you tell us a little bit about the first component and its

derivation biologically speaking of endomorphy?

Dr. Sheldon: I’ll try. There are, of course, three biological payers in a living

organism. There is the inside basic layer which is called endomorphy, or lowest component,

inside component. And then there is the middle layer of mesomorphy, or middle component,

and then the outer layer called ectomorphy, which simply means outside. That’s all

ecto means. Now from the endomorphy, called inside, component there develop the most vital

organs of the body, at least the most fundamentally vital, namely the digestive tract, and

the inside, or endomorphic part of any living body of any species is really that set of

structures with which the individual of that species is digesting. And without digesting,

it is a little difficult to live.

Dr. Paschal: Now how about the mesomorph?

Dr. Sheldon: The mesomorphic part of a living organism is the hard part. It’s the

middle part, that part which is strong and firm and hard. First, the skeletal system, of

course, and then attached to the skeletal system, the muscles, and then attached to the

muscles, all of the rest of the outside ectomorphic part of the body. So first you have

the endo, the inner basic foundation of the body, and then the meso, the bone, muscle and

connective tissue which holds everything together and gives it shape and form. Otherwise,

you couldn’t tell whether I am a buffalo or a bed but or a mud turtle, you see, but

if you know the human structure and know what its meso looks like, you can look at a

person and by standard measurements and by estimates, if you have had some experience, you

can state what the degree of meso is. Not ecto is the higher and later elaboration of what

originally had to have spread out from these inner layers. The ectomorphy is simply the

outside surface of the body, and the outside surface of the body, of course, is developed

into skin, and into the nervous system, including the brain, of course. If you didn’t

have any ecto you wouldn’t have any brain, you see.

Dr. Paschal: Well, it looks like this on the chart – stretched out, tall, usually,

and lean.

Dr. Sheldon: Ectomorphs don’t have to be tall, but with reference to their mass

they have great surface. The surface area of an ectomorph is much greater with respect to

his mass than that of a meso or an endo. An endo approaches spherical form.

Jim: Sheldon carried out a similar project to determine the basic factors of

temperament, and found temperamental components corresponding to these basic elements of

physique.

Louise Ames, the noted child psychologist, who later worked with Sheldon at Gesell

Institute in New Haven (Connecticut) describes the practical use to which these

temperament traits can be put.

Louise Ames: In relation to the parents’ questions, the parents who fret so: they

have a child who can’t get to sleep, the family is upset, they use disciplinary

measures about the whole thing, the child is upset, and many parents apparently find it

extremely useful to know that the child with an ectomorphic physique finds transitions

difficult, for instance, from waking to sleeping, and from sleep to waking, and that such

a child quite normally lies awake for an hour or more at night, and therefore if they

appreciate that it is just the child’s body, he’s not being tiresome and

bothersome, they are willing to provide a night light, if necessary, let a child road

later than they think is desirable, or have music available, or even allow the child to

play with a pet. And similarly, in the morning it bugs some of them that it is so hard to

get the child out of bed, and they think he is just being resistant, but if they can

understand that, just as some adults with an alarm clock need an extra ten minutes, I

think that they are willing to plan to give the child extra warning in the morning.

That’s one useful thing.

Parents of endomorphs don’t seem to need much support from the Sheldon concepts.

They are pleased to know that their child fits with what Sheldon says, but they don’t

seem to have that many problems. The parents of ectomorphs seem to have the most problems.

Sleeping is a real problem. Eating is a real problem. The child, they will say on the

phone, "My child doesn’t eat enough to keep himself alive. He hasn’t eaten

anything for 3 or 4 weeks!" and in comes the parents with a good healthy, normal,

skinny ectomorphic child. I think we have probably helped more ectomorphic children about

eating than anything else. We’ve tried to assure their parents they don’t need

three good solid meals a day. They don’t necessarily need or want to eat a great

deal.

Another place where many parents, especially as the children get older and into the

teens, where parents find the Sheldon work useful is the friendship bit. They worry

terribly if their children aren’t popular. I think parents worry a lot if their boys

aren’t popular, and they worry even worse if their girls aren’t popular. If

their girls aren’t popular, how are they ever going to get married and lead a normal

life, they seem to think, and so if a teenage girl isn’t popular, it’s very

useful to explain to the parents that if she manages one good friend, she does real well,

and that many ectomorphic children are comfortable at home by themselves, and so the

parents don’t add to the child’s problem by a lot of nagging.

At any rate, I do think the ectomorph has the most problems, and has the most

difficulty in just the ordinary things of life, and I think for parents to understand the

appreciate that, it helps a lot of them to lay off. Especially often an ectomorphic child

has at least one ectomorphic parent, and then when the parent clues in and say,

"That’s exactly the way I was, but I didn’t want him or her to have the

same difficulty," you explain this child with the same body is going to have the same

difficulties.

The other kind of child whom I think we can help, and I think parents are helped, by

understanding Sheldon is the mesomorph. Just a week ago a little boy came in just over 6

years old, and the parents’ problem is he is so loud, and he is so noisy, and has so

much trouble in school doing what the teacher says he should, he is so rebellious. We had

the time to play down the fact that this very mesomorphic little boy may have lots of

disciplinary problems in school, but at least I think the parents were helped to know that

mesomorphy has its good side. Mesomorphs can be leaders and can be very, very effective in

life, popular, and children like them, and especially when they get into athletics the

school is going to appreciate them, but that they are going to be loud and noisy and

aggressive, and that they do need acceptable outlets for this sort of thing. And when a

mesomorphic child in kindergarten, first and second grade gets in trouble with the

teacher, this is the time to realize he needs help rather than punishment. All of these

things I find extremely interesting for parents, and it is a great regret to me that this

kind of thing isn’t spread around more and isn’t more popular, and people

don’t talk about it.

Jim: Sheldon completed medical school, and went on a tour of Europe to visit the great

psychologists, and then returned to Chicago to give a course. Roland Elderkin, one of his

students, was so struck by his words that he was to devote many years to working with him.

Roland Elderkin: Well, the first time I ever heard of the man was in the fall of 1936

when I was in Chicago Theological Seminary. He taught a course called "Psychological

Approach to Religion," and I took his course. He wasn’t a person of physical

accomplishments, but his wit was sparkling. Every meeting we had there was a sparkle of

wit. Sheldon delighted in poking holes into the holy. He loved to tease and needle people

in a rapier sort of way, not realizing most of the time they took it as an offense rather

than something humorous.

Jim: From Chicago Sheldon moved on to Harvard where he gave some courses, and he soon

met up again with Roland Elderkin and made a new friend in Emil Hartl who was running the

Hayden Goodwill Inn for troubled boys.

Emil Hartl: I met him with Roland Elderkin when we looked him up because we learned he

was across the river at Harvard University with Ernest Hooten. We were interested in

looking him up because I was interested as the director of the Hayden Goodwill Inn School

in securing him as our potential diagnostician in our clinical approach to working with

our teenage boys. He agreed to give us quite a time, so he came Thursday evening, would

immediately go up to his quarters, and we would have laid out for him all the clinical

background of a given boy. We usually tried to have about three that he would see. There

would be a clinical conference the next morning. He was already beginning to be, I would

say, a celebrity in his field.

He had a high interest in adding the somatotypes in the clinical perspective, very

creative and upbeat. There was enthusiasm on a wide basis. Life magazine had an

article, a rather interesting one. Harper’s magazine had an article. So these

were Sheldon’s upbeat days.

Jim: Sheldon served in the Army in World War II and became seriously ill with a

lymphatic cancer. After the war he moved to New York as director of Columbia

University’s Constitution Clinic, and it seemed like his daring gamble to mount a new

attack on the problem of body and temperament was going to succeed. His work was spreading

widely. It was taken up, for example, by the physical anthropologists C. Wesley and Helen

Dupertuis who were to travel all over the world in their quest for a structural profile

based on bodily measurements that could serve as a kind of morphological fingerprint and

correlate with Sheldon’s somatotypes.

Their work, as well as Sheldon’s, benefited from the support and advice of Eugene

McDermott, one of the founders of Texas Instruments. Ashton Tenney, a New York

psychologist, recalls the years he worked with Sheldon and the impact Sheldon had made on

him.

Ashton Tenney: Well, if we don’t come to grips with the whole problem and question

of human individual differences, we are really not going to get a handle on psychotherapy,

on health, or any of these things, because everybody, in my opinion, like a snowflake, is

different from everybody else, and he realized that everybody was different, but that

there were certain limits that nature tolerates to allow a difference, and somebody has to

come along and solve the problem of defining and describing and explaining and correlating

the nature of individual differences with the very facts of life.

Well, back in the 60s and 70s there used to be a lot of talk about people wanting to

find out who they were, "Who am I?", and when you raise that question, what are

you talking about? Are you talking about who ma I culturally, who am I ethnically, or who

am I physically, or who am I intellectually, and if you are going to get your act

together, you better know who you are in a great variety of circumstances.

When I was a young man I would very much have liked to have been an athlete as

that’s what most young men appear to want to be. I would have liked to have gone to

West Point. But I realized I was not a mesomorph, and no way could I reach that port of

achievement. I had to find out who I was. The way I found out who I was was to become

associated with William Sheldon. He gave me a lot of insight into what my potential and

limitations were, and when I gave up what he would have called somatoerotic aspirations,

well, then I could function a little bit better. I didn’t try to be some big football

player, or some big basketball player, and some other successful athlete.

I think in a certain sense Sheldon was interested in finding out who he was in terms of

his career and what he did with his career because he looked like an adventurer who really

explored his universe, and tried to come up with some answers as to who he was and what

other people were, what his relationship was to the universe that he found himself in, and

I admired what he was endeavoring to do, and felt that he gave me more understanding of

myself than anybody else has ever done in my life, and I appreciated it.

Jim: Throughout these years Sheldon was preoccupied with the objections that were

raised about his earlier work which claimed that his somatotyping was too subjective, and

he devoted himself to the immensely complicated task of trying to find a completely

objective way in which to determine a person’s somatotype.

But these later years were a personal and professional turning point for him, as well.

His health had been severely damaged during the war, and the criticisms of his earlier

work rode the rising tide of a neo-Freudian environmentalism which had little sympathy

with Sheldon’s biological approach. But Sheldon took all these things personally. He

found himself more and more out of step with the hustle of a new urban America in the

making, and his feelings, so much bound up with his New England boyhood, rebelled. He

railed against city life and what he called urban wasters, and turned his sarcasm even

against his coworkers and colleagues, the very people he needed so that his work would

grow and have a future when he was gone. Dr. Edward Humphreys, a New Jersey psychiatrist,

recalls the positive impact Sheldon could have on people.

Edward Humphreys: Well, I looked on him really as the king of the constitutionalists if

you want to sum it up that way. At that time I felt he was a great man. There are

certainly many people who disagreed with me on that point, but I still think he made a

tremendous contribution to the field, and I think it is urgently in need for a restudy, a

re-analysis, and development of new orientations so that the whole field is brought

together in more explicit fashion.

Jim: In 1971 Sheldon moved to Scott St. in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just a few steps

away from William James’ house, where he ended his life surrounded by some of his

devoted friends like Dorothy Pascal and Edward Monnelly. Dr. Monnelly, now a staff

psychiatrist for the Veteran’s Administration in Boston, and an expert on

Sheldon’s psychology, was present during those last years.

Edward Monnelly: When I met Sheldon and had most of my contact with him was from 1973

on, and he would have been in his 70s living at Scott St. in Cambridge, he still kept very

active with his projects. We worked with him fairly intensively several times a week on

the follow-up of the book he had authored, Varieties of Delinquent Youth. We would

review the materials that would come in on the 200 cases in that book, and updating the

ratings that had been made in the first book. This was approximately a 30-year follow-up

of some of these men. It was interesting to me how well Sheldon could, if you will, put

his finger on what made these boys then, now men, tick, and some of the observations were

very prognostic, and even prophetic, you might say. He would try to set up a procedure to

be accurate and careful. He was not a quick or maybe even a sloppy worker in that regard,

and I think many are. He didn’t like to take short-cuts, and that, I think, has in a

way held him back.

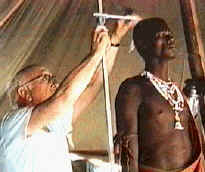

Jim: Ironically Sheldon finally did create an objective method of somatotyping, but it

was unveiled to a world that by then was largely indifferent. Dr. Monnelly demonstrates

how straight-forward it is.

Edward Monnelly: For many years the somatotype was criticized as being perhaps

subjective, and even though Sheldon tried to develop tables to give some objectification

to the somatotype, there was still this criticism, so he worked for many years on

developing a set of indices that would function as an objective way of determining

somatotype. The three indices that he came upon were maximal height, the so-called

somatotyping ponderal index at maximal weight, and the trunk index. Now maximal height is

very easy to determine. Somatotyping ponderal index is simply height over the cube root of

weight, using the person’s maximal weight, and that gives an index of a person’s

massiveness, you might say. But then, in order to be able to distinguish somebody’s

massiveness between how much of it is due to the endomorphic component, the fatty tissues,

if you will, and the mesomorphic component, the more or less lean tissues, the bone and

muscle, Sheldon developed what he calls the trunk index, and basically what that does is

to measure the area of the chest over the lower abdominal area by means of using a

planimeter which is simply a tool that measures areas, and it is fairly easy to do. You

anchor the somatotype photograph, and you make a set of marks at the anatomical waist, and

at the neckline. That will give you the upper trunk. And then at the gluteal fold you make

another mark, and that will give you the abdominal area, and then you set up your

planimeter, zero it out, and then carefully run around those edges, as I am doing here,

take your reading, and that will give us the lower segment. Then do the upper segment, the

upper trunk. You take your reading for that, and then the ratio of those two numbers will

give you the so-called trunk index. With those three parameters, the maximal height, the

somatotyping ponderal index, and the trunk index, you can enter the tables and find the

person’s somtatotype on a more objective basis.

Because the tables have been set up, you can do a less exacting procedure to determine

a person’s somatotype. You will have to take a person’s height very accurately,

and of course, you should try to get an accurate weight history, also, and then doing the

computation for the somatotyping ponderal index is fairly simple. Everyone has a pocket

computer, and it is just height over the cube root of weight. So if you have that

information – a person’s maximal height and information on their maximal weight

– you can determine the somatotyping ponderal index, and then you can go to the

tables, and a fairly easy way to do that would be to sort of make a guesstimation,

perhaps, of one of the components – maybe you would want to pick mesomorphy, the

muscular and structural component. If it is a man you might think that the average is in

the area of 4 to 4 ½. If they look very muscular you might go a little higher to 5. If

they don’t look quite as muscular you might go a little lower. So you might try out

certain mesomorphic possibilities – say 4 ½. If you go to that lever, then you can

see in the table at a certain age that they should weigh a certain amount, and should also

be a certain height, and if they are not that height, then you can go one step up or one

step down. So it is possible to fit all the components together – the three

components I mentioned – without actually doing the photograph, and taking all the

measurements precisely. It won’t be quite as precise, but it should be good enough,

and it will give some very good information, I think, to a person.

Jim: Sheldon died on September 16, 1977 and is buried here in Pawtuxet not far from

where he was born, and buried with him, largely because of his own doing, was interest in

the work that he had devoted his life to. That work now lies fallow, waiting for someone

to recognize it for what it was – one of the first and most important fruits of

American psychology. |

|