CHAPTER 1 THE RAT RACE

San Diego, 1973. One of America’s most beautiful cities. Palm trees, balmy breezes and inviting beaches. This is where we wanted to live and raise our family.

Our dream was to buy our own home, go to a well-paying job that was deeply satisfying, enjoy the cultural activities of the city, have a wide circle of friends, and travel to interesting places during leisurely vacations. We were young, full of energy and ready to start our life in the city of our choice.

But the dream began to fade as we faced harsh economic realities. Many others had come to San Diego for the same reasons. It had taken my husband Jim five months of job-hunting to find work, and his hours were spent in a hermetically sealed building shuffling papers. We were living in the cheapest apartment we could find in a neighborhood of blaring stereos, noisy Saturday night parties and small terrors. Our second child was on the way and the life we wanted to live always seemed beyond our reach. Even with the inexpensive apartment and a strict budget we managed to save only a small amount of money each month. If we were to improve our situation chances were high that I would have to go to work, as well, leaving our two little ones with baby-sitters or day-care centers. Even now precious family life existed on leftover time. During the day I would take care of our infant daughter, Elizabeth, and do all the errands I could so that when we did get together we would be free to enjoy ourselves. We cherished our time together as a family. We loved to have long conversations, or just read and think. But that time was far too short and almost all of our energies were taken up with working and scrimping to save for an uncertain future.

What was our future? If we followed the trend of other families like ourselves we would work up the ladder within the present job and earn more money, or we would eventually switch to a job we liked better. With me working, too, we might be eligible for a mortgage, buy our home, spend 20 or 30 years paying for it, see our children as much as we could, and hope that we would all be able to withstand the stresses and strains of a fragmented family life. When we reached 65 we would retire. By then, of course, our children would be grown and raising families of their own and we would find leisure activities to fill up the time remaining to us. If, of course, we lived that long.

Our hearts were heavy. We didn’t like the kind of life we were living now plagued by no time, money, space, privacy or quiet, and even with more money and a better place to live we didn’t know how the situation would be greatly improved. Our time would still be eaten up in working. But what choice did we really have?

Conspicuous Consumption ReportsHow were other people reacting to the frustrations of the rat race? Jim started bringing home stories from the office that were at first amusing and then puzzling: Mrs. A bought an expensive couch, Mr. B drove up in a new sports car, Miss C indulged in a hot tub, Mrs. D had an addition built on her house, and Mr. and Mrs. E flew to Hawaii for their vacation. All these purchases, of course, were paid for on credit.

Why were they buying these things on a regular basis? While we brought our peanut butter sandwiches along on a day trip, they would go to one of the fancier restaurants. While we bought our clothes at a secondhand store, they were charging a new outfit every week or two to their account. While we were economizing on food, they would bring home a thick steak. We needed to save money so that some day we would be able to change our situation, though just what we meant by that was unclear. But they were spending it just as fast, if not faster, than they earned it. It didn’t seem to concern them that they were living from paycheck to paycheck, or that there might be a rainy day.

Then it dawned on us what was happening. We are expected to work all our adult lives, whether we like the job or not, so they were trying to make it all seem worthwhile.

Instant GratificationNot only are we encouraged to gratify ourselves, we are urged to gratify ourselves now. Why wait? Besides, how much time do we have for ourselves after the working day is done and the errands are run? We can’t afford to wait.

The dinner at the fast-food place, the soda bought on the run while doing errands, the package of sugar doughnuts snatched for dessert, the magazine or pack of chewing gum added to our pile of groceries while we wait for our turn at the cash register all become automatic. Instant gratification becomes an integral part of our lives. But with all these little, and sometimes big pleasures comes the moan of where all the money is going.

The new red sports car sat in the hot sun all day while the owner didn’t even have a window to look out of while he worked; the new outfit was half-hidden behind the desk and the couch didn’t even get sat on until the weekend. But they were there. They existed. They proved that all these hours were not wasted. Or did they?

MoneyBut what about us? What were we going to do about our future? We had no idea, but we knew that money was the first problem we had to face and solve if we were to shape a lifestyle of our own. But the only way we knew how to get it was to work for someone else. A job meant 40 hours a week doing work someone else told us to do. If we don’t like the job we are afraid to quit because we might not get another one right away, and to switch jobs makes our work record erratic, labeling us unreliable. It means we have to live close to the job in order to cut down on commuter time, and that usually means paying rent we have no control over or taking on a mortgage. If we get fired we are under tremendous pressure to find another job as soon as possible before we lose our house, our savings, our car and our precious self-esteem. The loss of a job means we are more rapidly than we thought possible faced with POVERTY. If we do lose our job, then people assume there must be something wrong with us and it is harder to get the next one. It means we have to work until retirement if we expect to get pension benefits, and our time with our family, and for our hobbies and our travels is very limited. If the job becomes boring, if an overpowering sense of exhaustion comes over us which we can’t seem to shake, if our nerves are being stretched by fighting traffic, our boss and never enough money, that’s our problem. If our company folds and we wait in unemployment lines, that’s our problem. If we need a raise and don’t get one, that’s our problem. If there is a general cutback and we are cut back, too bad. If we are passed over when promotion time comes, tough luck. If we want to change our job or enter another career altogether, it usually means we will have to go back to school at night and hope our gamble of extra hours over the books will be worth it. If a crisis is going on at home we are still required to be on the job and handle our personal affairs on our own time, what little of it there is left. It means that personal time is at the end of a long and exhausting day and our hectic weekends are filled with errands and jobs around the house.

We looked around us and saw too many broken marriages and suffering children. We saw too many purchases piled up in the garage and too few hours of loving communication within the home. Such a life held no appeal for us. We felt there must be a better way, and we were at a crucial time in our lives when we had to find it, and find it now, before we succumbed to the house in suburbia and a full-time, life-long job.

We felt we needed time, lots of it, to reflect on what life was all about, time to experiment with new possibilities, time to learn and grow. The only time we felt truly alive was on our days off and during vacations. But those days passed all too soon and before we knew it Jim was back behind the desk again. Free time had always given us the opportunity to study, question, wonder and travel, and we were greedy for more. But what were we to do? Since we were forced to spend most of our day earning money we turned our attention to money, itself, in the hopes that we would get a clue to a new future.

The Beginning of MoneyMoney. What is it? Where did it come from? Why did it seem to have such power over us? In our society money equals Success, Security, Power and Happiness. Money when spoken of, and it is spoken of often, is usually an emotional topic. It is hard for us to think of it objectively because we tend to define ourselves in terms of how much we have or don’t have. Money is the ticket to the fancy neighborhood or the right school and the newest car. Money makes it easy to see where we stand in society. Our clothes, our job, where we go out to eat and where we spend our vacations all indicate our worth. If we have only enough money to get by then we automatically become marginal.

We needed to look at money objectively. We had to separate it from its emotional connotations and reduce it to just another fact in our lives. And so we began to study money.

Looking BackOur evening hours were spent reading about the stock market, puts and calls, convertible bonds, hedging and mutual funds. We studied the national debt, the floating dollar, arbitrage, treasury bills, gold, silver, interest rates and the price of pork bellies. A frost in Florida, a drought in the Midwest, or the government subsidizing farmers all threatened to upset the delicate balance of the international economy. We found ourselves confused and buffeted by economic factors we barely understood and could do virtually nothing about.

Finally, weary and discouraged, we let our minds wander back to the time when money was pretty feathers or unusual shells. The simplicity of those primitive times attracted us. We read about the Indians before the white man came, we tried to picture California before there were cities and freeways, and we imagined the ancient Chumash Indians of the central California coast gathering clams and fishing for dinner. Depressions, recessions and runaway inflations were unknown then, and people looked at the rising sun rather than the ticker tape to see if the day was going to be a good one.

But those times were gone forever and we were left with the roar of the jets overhead. Or were they? Thinking about primitive peoples made us dream of a tropical island where we, too, could escape today’s complicated world and be close to nature, as well. Our economic tomes were returned to the library in exchange for books on little known islands of the Caribbean.

The Tropical Island FantasyWhat is the tropical island fantasy? It is the dream that somewhere lies a beautiful, untouched island filled with fruit-laden trees, majestic palms and lush foliage. On this island the warmth of the sun is balmy, the nights comfortable and all our physical needs are met graciously. Every morning we wake up to the singing of the birds, and as we stand on the palm-lined beach watching the waves break gently on the sand we are filled with a sense of excitement and energy, wondering what new adventures await us as we fish for dinner or explore new caves in the mountains. At night we sleep in our palm-thatched hut, tired and happy after a fulfilling day of communing with nature.

There are no alarm clocks, bosses, traffic, fights with the neighbors, taxes, nerves and ulcers, mortgages or sickness, and no need for money at all. What we need are our intelligent minds, our strong bodies, and a perfect mate who understands and loves us completely. Later our beautiful children will help with the fishing.

All of us yearn for this tropical island in one form or another, and some of us even try to find it, for the image of this perfect world lies deep within us.

The Tropical Island Fantasy – VisitedThe more we thought about life before economics got so complicated the more we yearned for a true alternative. We searched through our piles of books looking for an island that would satisfy our needs. We finally found one in the Western Caribbean that the tourists had barely discovered, and we decided to see it for ourselves. It was green and hilly with palm-lined beaches, and its history spoke of pirates and ancient ruins. It was called Roatan, and it was located off the coast of Honduras.

It was May and vacation time was coming up. Jim decided to use it to investigate the island for us. I was 5 months pregnant and our daughter Elizabeth had just turned one, so we felt I should stay home. Besides, the trip was expensive.

Jim had to start taking anti-malarial pills two weeks before departure day, but as I watched him take his first pill we both made a quick decision; we would all go. For him to go alone leaving us behind was not a happy thought. I wanted to be there, too, to see if it would be a good place for us to move to and begin a new life. We hurriedly got more pills and I mashed up our daughter’s in her bananas and yogurt. Our budget would suffer, but for once we didn’t care.

We flew from Los Angeles to Guatemala City and then on to San Pedro Sula, Honduras. We sat in the airport sweating until the little DC-3 that was to take us to the Bay Islands was ready. One of the passengers was a large gentleman, but I didn’t give him a thought until the stewardess asked everyone their weight. She was checking to be sure the plane could take off. Help! What were we getting into?

We did take off, flew over the banana plantations on the coast and then the turquoise waters of the Caribbean. Beautiful. But the plane rattled alarmingly and my heart almost stopped when I saw the runway of our first destination - a short stretch of coral beach ending abruptly in the ocean. The pilot had one chance to land before we all took a swim in the sea. The next hop brought us to the green and hilly island of Roatan.

When we got off the plane we entered a new world: no paved roads, only a few 4-wheel-drive vehicles, houses on stilts, pigs rooting along the main street of Coxen’s Hole, the largest town, and no one in a rush to do anything.

We went to one of the modest hotels. That evening when we turned on the light bugs we never even dreamed existed flooded through the screenless windows and we quickly decided we preferred darkness to company. And it was hot and humid. We managed to survive until about 10 a.m., but then the heat wilted our bodies and our brains. We couldn’t think. We sat in our room and read novels. But the people of the island kept assuring us the trade winds would come soon. And they did. Now we had hot wind blowing on us instead of no wind at all.

"Listen," we said to each other, "We came all this way not to spend our time reading novels in some room. This is our tropical island paradise and we’re going to see it." So we took one of the jeeps to the other side of the island through thick jungle on a dirt road. This new side had white sandy beaches bordered with palm trees. The water was crystal clear and it matched perfectly our dream of the island paradise. We stayed at a tiny inn and its owner’s wife was a fabulous cook; she produced freshly squeezed orange juice from their own grove, fish fresh from the sea, and mouth-watering coconut desserts. It was delightful, but our brains still clicked off at 10 a.m. Discouraging. Most mornings we walked along the beach. We saw children on their way to school, a man working in his sandy yard, mothers running to tell the jeep driver to pick up a chicken for them in town. A young American couple was building a house on the top of a hill out of cinder blocks. To make the mortar they used sea water and had to make frequent trips down their steep hill and then lug their buckets back up again. But they were building their dream, and it gave us hope that we could build ours, too.

On one of our walks we ran into an older lady who turned out to be the island midwife. She entertained us with many stories, and then she decided to predict if I was to have a boy or girl and she did it by looking at the back of my little daughter’s knee. And it turned out she was right – a boy.

An islander took us out in his dory so we could see the tropical fish in the reefs. While he and Jim snorkeled about I became fascinated by the flashing colors of the tiny fish. But my spell was broken when our guide let out a yell. He had stepped on a sea urchin and our trip was cut short.

We loved our stay on the island. There was land we could buy and the people were easy to get to know, but we hesitated. We obviously weren’t made for the hot climate. Making money would be a problem, too. Many of the men worked elsewhere and sent it home to their wives and children. Most of the food was imported and was quite expensive. The possibility of contracting malaria or amoebic dysentery made us feel uncomfortable, as well. But our experience taught us an important lesson. Not everyone was living in an American-style suburbia and maybe, just maybe, we didn’t have to, either.

On our way home we traveled high into the mountains of Guatemala to a little town at the edge of Lake Atitlan called Panajachel. As the local bus filled with natives, chickens, and us began its slow ascent up winding roads our brains began to clear. We saw waterfalls, tiny farms and attractive Indians in their traditional dress. The centuries fell away, we were in the land of eternal spring, and we loved it.

The simplicity of the people here had a strong appeal for us. Market day was filled with color, excitement, smells and fun. There were mounds of bananas, tomatoes, pineapples and vegetables of all sorts we could buy for just pennies. We would also be able to rent a house for a small sum, as well, if we chose to stay.

It was tempting, but something stopped us. We would always stick out as foreigners here. This particular paradise was not our paradise. We would not try to live here, but our personal resolve to find our own alternative was becoming rock solid. Our future was still a mystery, but we were determined to keep looking for an answer.

CHAPTER 2 LEAVING

We started making new plans, looked at maps and fixed up our old Volkswagen camper for a trip we now knew was inevitable. We made sure the tiny kitchen in the camper worked, and we transformed an ordinary drawer into a miniature crib for our soon to be born baby. Then we strapped the drawer securely behind my seat for easy reach, made room for the diaper pail, built a rack on the roof to hold supplies, and we were ready.

When our son, John, was three weeks old we collected the last paycheck, moved into the camper, gave the apartment back to the mice, and left the city and what we knew as security behind. Where were we going? We didn’t know – something vague about being near a forest. What were we going to do once we got there beyond having time to meditate and reflect? We didn’t know that, either, but first we had to leave the city and then go on from there.

What happened? Well, on the first day our engine blew up, we were towed 20 miles; they locked our little home up until Monday, and we were forced to find a motel. Besides food and lodging, the repair bill came to $336, a significant part of our hard-earned savings. What a beginning!

One week later, however, found us renting a cabin near a beautiful pine forest in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. We were within walking distance of the village, and we were surrounded by peace and quiet, for it was November and the owners of this community of second homes came only in the summer. We enjoyed sitting by the fire and baking in the kitchen. We breathed in the mountain air, meditated, hiked in the forest and let our minds settle down to this new way of life.

On the negative side we were living in an uninsulated summer cottage, the weather got colder, the propane heat was rushing out the cracks, and as the weeks went by we were getting nervous. Our carefully saved money was disappearing, and we knew we would have to do something soon. And so, despite all our resistances, we turned to the only way we knew how to earn money: work for someone else. We tried everything to find employment, from a job in a nearby city working with juvenile offenders to guarding the local dump. Results: nothing. Too much education or not the right kind.

As we searched we began to set up our own guidelines for the perfect job: part-time and/or seasonal, giving us enough money for the year without tying us down. But we were exhausting all the possibilities for local employment, and tension built up. Suddenly one day came the breakthrough: "We don’t need a job, we need money! Let’s create our own business." For the first time there was the possibility of not having to look for a job, hat-in-hand. We mentally shredded the job list, threw off our depression of how we must be very dumb because we could not find work, and began to look within ourselves rather than in the disinterested eyes of society for a solution. We might not be great job prospects but we did have some brains. Why not use them for our own uses rather than hiring them out? What could we do? Again, we didn’t know, but our thinking had been happily turned around. We didn’t have to wait for the telephone to ring to tell us what our fate was. It was up to us to tell us what to do. Surely we could figure something out.

Our Own BusinessWe left the cabin and headed back to San Diego, but this time with a difference: we had our eyes wide open, looking for businesses we might pursue. We saw successful self-employed people, but they usually had one fault in common: their 40-hour week had turned into a 60-hour one, or more. But many of them were using not only their heads but their hands. Hands! Going to school and working in an office made you forget you even had them. Working with your hands was somehow inferior. Our hands had been useless appendages, but now they began to feel new life. What if we could earn a living by using them? What was unthinkable before suddenly became exciting.

We visited the one really successful craftsperson we knew in San Diego who taught us how to make mirrored planters with carved wooden frames, with the agreement we would move to Connecticut where I had grown up, set up our business and pay him royalties on his designs. 3,000 miles later we rented an apartment as well as the basement of a store for our workshop. We bought the tools we needed and then started to work. But just turning on these powerful tools made our hands sweaty. Part of the work was taking large sheets of mirror and cutting them up into smaller ones to be put in the carved wooden frames we were making. But the thought of ruining those expensive 4 feet x 8 feet sheets of mirror made my blood run cold. Fortunately I knew a lady who used to work in the local glass factory, and I asked her to help me. She gladly came to the shop, picked up a glass cutter, and ground away at the mirrors, making mistakes, trying to remember how to do it. But she did help, for if she could treat the material like that without worrying about it, then surely I could do the same. And I did. After all, what choice did I have? The idea of using our hands was one thing, but actually doing it took courage. Buying hundreds of feet of wood, transforming that wood into carved frames, staining and assembling them, and cutting and mounting the mirrors, were all things we had to learn.

The second and even more important problem was how to sell them once they began to pile up in the back room. We heard about a craft show an hour away, we called up the lady who was running it, got permission to come, and loaded up the VW bus not only with our freshly made planters, but with our hopes for the future.

We set up with the other craftsmen, the people came, and we began to sell! And we kept selling until we were sold out! There was a special magic in seeing people willing and even eager to pay good money for what we had made, and the gamble of taking our future into our own hands was paying off.

Not all shows were successful. At some we sat there and worried about making enough to cover the fee. At others we found ourselves in the middle of a field where no one came. But we learned by trial and error, and eventually figured out which were the best shows to go to, and which to avoid. We settled down to steady production, organized our own work time, schedules, and best of all, banked our own money.

But the important lesson was that the woodworking itself was not the key to success. The key was in our new way of thinking. If woodworking failed, then we could try other things, or two things at once. For the first time we became the active ingredient in the process. No one had to give us permission. No one had to hire us. No one had to put us on their payroll, or tell us what to do. We gave ourselves permission to run a new business. We told each other how much to work, how much to try to earn, and how much vacation to take.

After running the business for a couple of years we went to Florida in the winter. For the first time in our work lives we were worry-free. We did not have to quit a job in order to relax and enjoy the sun. We knew that when we felt like it we would start up production again. And the money would begin to come in again. It was as simple as that. We did not have to worry about yet another round of job hunting once our vacation was over. Our self-esteem would not undergo brutal punishment as the rejections piled up. We had turned ourselves around from being a statistic among the unemployed to happy, self-employed, independent, confident people.

In working with our hands we also had to use our heads. We had to organize the materials, the production, the scheduling of the shows, the accounts, etc. If we didn’t do our own thinking, no one was going to do it for us. Our heads and our hands learned to work together, and our whole selves were better off for it. I feel sad when I read about the mental tortures unemployed people go through, looking for jobs, watching their savings disappear, and falling into the paralysis of depression. I can too well understand it, and I hope that if you are in that state, that you, too, will look down at your hands and start moving your thinking around.

There is always the temptation to let a successful small business grow larger. But we had not been happy as employees and we strongly suspected that being employers wouldn’t be much better. Not only would we have to support ourselves, but others, as well, and in the process our precious free time we now enjoyed while running our family business would disappear.

We had solved the problem of how to earn our living, but the weeks of sunbathing on Florida beaches awoke in us deeper desires. As we watched sea birds circle overhead, or bought fish in the market, as we let the magic of sunsets soak into our psyches, or watched sand pipers run along the ocean’s edge, we let ourselves think about the next step. The business was portable because it resided inside our heads. What were we going to do with this golden opportunity of financial freedom?

Nature was calling to us again, just as it had during our trip to the tropical island, but now we were better equipped to listen to it. We needed to live closer to nature, and our hands that were now alive in earning our living wanted to have control over the basics of life: food, fuel, shelter and water. We began to read books on self-sufficiency. We needed to own a piece of land where we could sculpt out our own unique lifestyle.

The Search for LandOctober 1977. We set out for California with an old $100 Buick pulling a 7 feet x 8 feet trailer that someone had made by hand, and started to look for land while camping in the State parks along the coast. A house on a lot was far beyond our financial means, but we imagined that five acres in the country would be nice, especially since all we knew were suburban lots or squeezed together houses in cities. We had only one nonnegotiable requirement: we wanted to pay for it all at once. It bothered us to think about a mortgage. Our business was not steady enough to assure our ability to pay for the land each month, and we couldn’t bear to worry about missing payments and jeopardizing everything we had worked for.

We also assumed that with the land would go electricity, telephone, maintained roads, etc. Any other idea never crossed our minds. Such amenities were part of our heritage. They were almost inalienable rights, and to live without them was unthinkable.

But then one memorable day, after weeks of searching, staring at plat maps, looking at land, writing to owners, making offers, and meeting nothing but large prices or refusals (and having given up on crowded California and come to Oregon) we noticed there were large tracts of uninhabited land. We also noticed something else: there were no paved roads, electricity or telephone lines, either. What if, we tentatively said to each other, we were to look for a piece of land away from the hookups? Perhaps then we could find a piece of land we can afford. The idea stunned us. Did that mean we would be on a permanent camping trip on our own land? But having our own place was becoming essential, and we were getting downright stubborn about no mortgage. So it seemed that a piece of remote land was our only choice.

Amateur Surveyors

Once we started looking for this remote piece of land we discovered that first you have to find it, literally. That little square on the plat map often turns into a treasure hunt. Compasses seem to jiggle around in alarming ways when you think you are holding them perfectly still, declination has to be considered, and the old surveying stakes have to be tracked down. Toddlers become marking posts, and bushes have to be walked over in order not to lose the tenuous line you are pursuing. "Don’t move, Johnny, (who was now almost 4) until Daddy tells you you can." "You’ll have to wait a little while for a drink of water, Elizabeth." "I know you’re standing in a bush." And as we drove back to town and our campsite, "You left what in the woods?"

What we thought was the correct piece could sometimes not be found again, due, of course, to our inexperience. We had come a long way from thinking you walked into a real estate office and plunked down your money, to getting our faces scratched by bushes in the back country. And we thought that once we found an owner who had a piece of land to sell, and we were willing to buy, then it would be a simple matter of exchanging money for land, right? Wrong. We painfully learned that even though people think they want to sell, when it comes down to the wire you can get some very interesting responses. For example, they may point out the boundary to you (which you and your children have already struggled to discover) and they shave off a few feet here and a hundred or two there. When you remark that his boundary doesn’t seem to match up with the one we discovered, things get even more interesting, and usually end up in no deal.

Or beware of the owner who is happy to sell the land to you, but if you haven’t checked up on the deed you might find out afterwards that there is a lien on it you will have to pay if you want it, or the owner has slipped in at the last moment a little clause which states you can have the land but he has the right to cut all the trees.

Also beware of the owner who points out the boundaries with a vague wave of his hand, and if you take his word for it and build a little cabin on it, you discover to your horror that it’s on the wrong piece of land! Your piece is a few hundred feet to the left or right, or whatever. I would like to tell you these things don’t happen, but they do.

Our Own LandA friendly real estate agent had been helping us as we looked at progressively more distant and wild sites, and he had seen our disappointment when several of the deals had fallen through. He looked at the kids, scratched his head and said if we really meant it about living away from all the amenities he had an idea. He remembered a piece that was no longer on the market, made a phone call and said there were 20 acres of land available in the middle of a national forest east of the Cascade Mountains near Crater Lake National Park.

One July morning Jim went to see it with him, and the next day Jim took me. For the first mile of dirt road I was excited and chattered along. During the second mile I was a little quieter. By the fifth mile I was totally silent. Not once during that whole ride did I see one sign of people! If we bought this land we would, it seemed, be totally isolated from everyone. But the next thing I knew we were scrambling up a hill thickly wooded with ponderosa pines and white firs. Once on the top we got glimpses of snow-covered mountains in the distance. No one had ever lived there before, we would own the whole top of the hill, and it had good southern exposure. Sold!

July 1978. Our first night there brought an ear-splitting thunder storm, accompanied by a tremendous crash, which turned out to be the top of a tall fir laden with cones that had snapped off and landed only a few feet away. The next morning our little son said, "Daddy, look at the deer." There in a clearing were four giant bull elk calmly staring at us, their racks majestic in the sun. They stood watching us long enough for us to take their picture. Then they turned and slowly loped away. Welcome home!

CHAPTER 3: HOME

Still not quite believing we actually owned a piece of land, we turned to the next problem: building a house. Previous experience: none. Opportunity to observe someone else build their own home: none. People to help us: none. Ideas: many. Fear and anxiety: overwhelming.

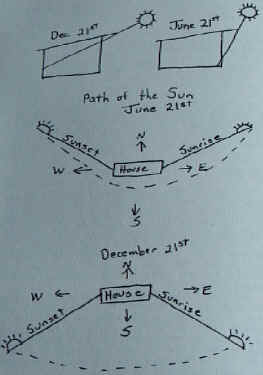

| The Sun We may not have known how to build, but we did know how to read, and the past couple of years had been spent doing just that – to distraction. Conclusion: we wanted to build a passive solar home, a home that would face south so that it could receive as much sunlight and therefore heat as possible. We believed in the theory of sun power and wanted to test it out. We knew we would have long, cold winters, and any extra help from the sun would be greatly appreciated. Our first problem, then, was to try to figure out the path the sun followed in winter. Using a compass, a level and a protractor we went from one possible site to another, trying to calculate just where the sun would come up in the southeast, how high it would get by noon, and where it would go down in the southwest. By a process of elimination we finally discovered the best site high on the southern side of our hillside. |

|

How large should the house be, and what should it be shaped like? We had been playing with house designs for months. We would pace out possible designs on vacant lots, parking lots, dirt roads, wherever we happened to be. We would pretend our house was going to be square, round, two-storied or dome-shaped. Each time we would imagine what it would look like, we would play with larger or smaller versions of the original idea, we would sketch it out on the ground with a stick or a piece of chalk, and we would let our minds live with that particular design for a day or two.

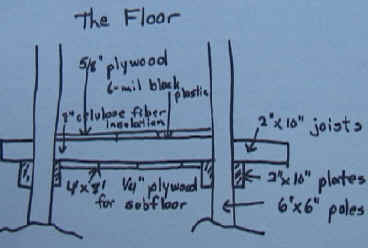

We eventually decided on just about the simplest possible design, a rectangular building 12 feet x 36 feet with a shed roof, the north wall lower than the south, and with no interior walls. The long south wall would have lots of windows, and the whole building would be small and well-insulated. We hoped such a building would be quick to build and easy to heat.

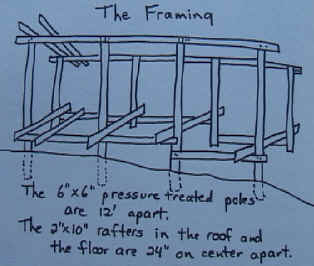

BuildingWe also wanted it to be a pole house. A pole house has no foundation aside from the poles that extend from 4 feet or so into the ground up to the roof. It is ideal for sloping land like our hillside, for it creates a minimal disturbance of the land. We finally gathered up our courage and ordered the framing from the local lumberyard.

| We dug the holes, put the treated poles

in the holes 12 feet apart, bolted or nailed on the beams, placed the rafters for the roof

and the floors on the beams, put in the floor, framed the walls, put on the roof, put on

the exterior siding, and after 5 weeks of dawn to dusk labor, moved in and took a

breather. It sounds orderly and logical, and building in itself is. But unfortunately we didn’t know what we were doing, so we spent as much energy trying to deal with our emotions as we did in doing the job. Here are some excerpts from my journal: |

|

August 21-22, 1978. The poles and framing arrive from the lumber yard, but the truck gets stuck half-way up the hill. We off-load it there. The rest of the road to the building site is a handmade one created by us simply cutting the brush out of the way. We load four of the heavy long 6 inch x 6 inch treated poles that will hold up the house into the old International pickup we have just bought, and race up the new road to avoid getting stuck. Then we do it again with the remaining four poles. |

|

|

|

This time we get stuck trying to go down. We simply didn’t realize that the road had to be compacted. We banged the passenger door, the gas cap, and the mirror trying to get unstuck. Then the truck wouldn’t start. While we were worrying about it we go ahead and put three of the poles in the holes we have been digging with a shovel, and as they got deeper, taking the dirt out with our hands. We finally get the truck going. We get unstuck, make it down to the lumber pile, and get stuck again.

August 23. Felt tired. Jim and I spent a couple of hours making a master list of all our needs and what our financial resources were. Then we went up and put the fourth post in… We lined all four up and put the bottom plates on… Exciting! Jim is using a bit and brace (to drill the holes to bolt the horizontal beams to the poles). The kids seem out of whack, but that is probably because they are not getting enough attention.

August 24. Jim and I spent the morning trying to put on a roof plate, but drilling didn’t work. (We ended up nailing the top plates on with long ring nails as we teetered on the top of makeshift ladders.) We tamped in 2½ post holes, making mud and using rocks. Didn’t look like we did much, but we did… We sat around a little and had a very good pancake dinner – before dark for once. Even washed ourselves a little.

August 25. Jim and I worked from 8 to 8. We put the top plates on the front row, put the four back posts in the holes, and braced up three. Also put some cement in two front holes. The last hole was really hard because Jim had to chip away at a rock. The sunset was beautiful!

August 26. First we braced up the last pole, measured, plumbed, etc. We put the bottom plates on the back row, then put some floor rafters in and nailed them in for more stability. Spent a great deal of time trying to put up the roof plate at the deep end. Got rather dangerous, but we finally succeeded. Another 12 hour day. And another quick meal – soup and hard-boiled eggs and saltines. Not bad!

Sept. 5. It rained the night before, and our floor section was ruined. We put in the framing for the kids’ room… It rained on and off all day. We framed the back wall in the rain, and then had to break off entirely (probably around 4) because it was raining too hard. Jim and I were soaked… That night I woke up and felt totally frustrated because of the rain. Jim talked with me for a while and I felt better. Everywhere I looked things were soggy and a big mess, trash was everywhere…

Sept. 6. Finished the ceiling and worked on framing the east side, and some of the west side windows in the kids’ room. Another day of rain…

Sept. 9. Another day of rain!

Sept. 11. No rain at all! We filled up a hole (one more to go). Finished putting on the roof plates (terrible job), and then spent the rest of the day putting on the exterior siding on the north and west wall. Very satisfying! We have been talking lately about what it is all about, and decided our house is really a "boat" in order for us to sail away…

Sept. 13. Rain! What a letdown! We stayed in the trailer and tried to plan the south wall.

Sept. 14. Went to work on the roof again. First I mopped up the plastic, and then we went to work. THE SUN WAS OUT ALL DAY! And it proved to be the Day of the Roof. We put insulation in and nailed on the plywood – until dusk. We must have worked about 13 hours, but we felt like we were over the hump. We could finally cover the whole roof with plastic.

Sept. 15. We spent all morning dragging each roofing roll on John’s bike (the car was in the shop getting fixed), and then getting each one up the ladder.

Sept. 18. The last few nights we have been eating before dark, which is a pleasure in itself. (Went down to 36 degrees in the trailer at night!)

Sept. 22. Spent the day putting exterior siding on the southeast wall.

Sept. 27. Started bringing things up to the house! Can’t believe it. Did some floor finishing work.

Sept. 30. John’s birthday, and moving day! Two loads did it. We are all moved. How neat to have a kitchen, even though it is rough. At night Johnny had his party and presents. I felt exhausted, but had fun at night.

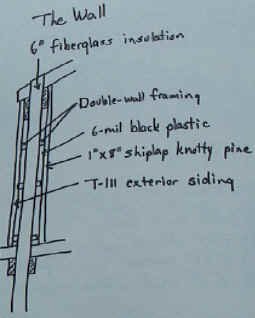

And so it went. The house was framed, and the exterior siding was on, but we had yet to put in a wood stove, and we needed to insulate the walls and put on their interior pine boards.

If you think of building a house like putting together a giant erector set, it’s not too bad, if, of course, you happen to know how the erector set goes together. All our books neglected to mention exactly what dimensions the beams and rafters should be, how thick the plywood for the floor and roof should be, etc. We had a table telling us the size of the rafters according to expected snow loads, but it wasn’t until the day after we finished the roof that we deciphered the charts and learned (with a tremendous sigh of relief) that our roof would hold up after all! Obviously we were not too mechanically inclined. We preferred sitting around reading stacks of books rather than getting out there and pounding on our thumbs with a hammer, but if we were to have a house of our own we had to build it ourselves. Period.

Our building tools were minimal. We needed a shovel, hammers and a level. What our eye told us was level differed radically from what the level said. We also needed a tape measure to measure between holes, a long piece of string to try to get our poles in line, and a chain saw to cut boards and openings for windows. But what we needed most was confidence, and that was sorely lacking.

What were our children doing all this time? Trying to stay out of our way, since their parents had been reduced to monosyllabic grunts, punctuated by not so socially acceptable words. They came in handy, however, for finding lost tools, or they washed dishes or peacefully played with new blocks of wood their parents were so thoughtfully producing for them. A wonderful new game was obviously going on – yippee!

HeatWe planned that the 8 feet x l2 feet middle section of the south wall would be windows. We assumed the wall would be straight up and down, but when we got to building it, we started playing with angles. The result: a slanted wall that not only gave us better solar gain but also dramatically transformed an ordinary rectangular house into an exciting one. (Such an innovation is possible with a pole house because the walls do not support the weight of the roof.)

Did the gamble of building a passive solar house pay off? Well, sometimes when it is 20 degrees out and the sun is shining we turn off the wood stove and do some January sunbathing, which is wonderful for the morale of the group. But one drawback of a pole house is that it is difficult to store the heat coming from the sun. Since it is perched on poles with no slab it lacks the mass necessary for solar storage.

Non-Instant Gratification TimeWe built our house without help. It was just the two of us trying to include all the good ideas we had read about and still keep the size of the house within reason. Later, when our muscles stopped aching and our bodies were not compelled to work incessantly, when we saw the sun streaming through our south-facing windows and realized the roof would not fall on us in the middle of winter, we were very glad we had taken the risk. Total cost of our 576 sq. ft. (counting the loft) sun-bright castle: $3,500!

| Our gamble was paying off handsomely, not only economically, but also in a deep feeling of satisfaction. We had actually done it. We looked around our home and knew exactly how it had been put together, and we also knew how it could be changed or added to if and when the time came. Our house was not a mystery to us. If something needed to be fixed we could fix it. If adjustments had to be made, we could make them. |  |

Our house was not static. As we grew the house could reflect and nurture that growth. It is as simple and organic as that. The house becomes a unique, growing, evolving, exciting center of family activities, parties, business ventures, crafts, a place where new parts of ourselves are not only discovered, but cautiously and then more boldly experimented with. Why should it be otherwise?

House Building ConclusionsBuilding our own house:

1. was not an impossible task that had to be left to professionals

2. brought us great economic freedom

3. opened our eyes to the natural forces around us, and most importantly,

4. created a space in which we not only ate and slept, but could work and play, learn and grow, and explore what the future held for us.

CHAPTER 4: PLEASE

DON'T DRINK THE TADPOLES,

AND OTHER BASICS

Water. You simply turned on the faucet and there it was. The only complaint might be that the hot water didn’t get to us fast enough.

And then we moved to the forest. The nearest source was miles away and we hauled it in 5-gallon plastic buckets. Water is heavy. One gallon weighs a little more than 8 pounds, a fact no one cares about when it comes in pipes. But the less water we would have to haul the less wear-and-tear there would be on both us and our truck.

Our very first thought was: we need a well. So we started digging holes and experimenting with makeshift well-drilling equipment, but that wonderful life-sustaining substance eluded us. And to have a professional well-driller was too expensive. Then, after considering the problem of a well from all possible angles without finding a solution it hit us: what we needed was water, not a well. There are occasional rain storms during the summer and lots of snow in the winter. We had to make the most of what we already had.

If it rained I would line up my buckets under the edge of the roof and feel wealthy if a dozen of them filled up. Later we graduated to a gutter system which funneled the water into 6-mil plastic-lined holes. The easily ripped plastic eventually gave way to more durable PVC pool liners. Then, if we heard rain on the roof in the night we would jump out of bed, scramble for the flashlight and race out to be very sure the rain was actually falling into the small pools. We would look in awe as we saw dozens of gallons fall effortlessly into them, all water we would not have to haul, water that was being gifted to us by nature and which we would use carefully. Some day we will probably have a well drilled, but for now we still bring in drinking water in the summer, we melt snow in the winter, and use the pool water for the garden.

But any inconvenience that we have suffered has been more than made up for by our new attitude towards water. No longer can we peacefully watch our town friends take a sip of water and throw the rest casually away. No longer can we feel comfortable with the 5-gallon flush or watch someone turn on the tap and then turn to do something else and let the water flow freely down the drain. Water is important and has captured our deep attention. We watch the sky, anticipate coming storms and try to make sure that everything is ready for the new influx. But it goes beyond that. To see the tip of each needle of a pine tree holding a single drop of water is to look upon our private treasury of diamonds, emeralds and rubies as the sun shines through each precious droplet.

WildlifeWhile the main purpose of the pools was to water our garden, we noticed with delight that something else was happening. Birds multiplied and we would get excited when a new kind appeared. Their splashing and calls became part of the background music of our day. A chickadee family would build its nest under one of our beams and we would tiptoe around on "fly day" when the babies discovered their wings. The pools were open to the sun and algae gradually changed the clear water of spring into dark green by autumn. Frogs would set up a deafening chorus every evening during mating season making the place sound like the Louisiana bayous, and soon there were hundreds of tadpoles. A doe and her fawn would make their way hesitatingly towards the pool in front of our house during the hot, dry days of summer. We didn’t dare breathe as they approached the water with every muscle poised to bolt away at the slightest noise. The fawn captivated us with his play, and through the months we watched his spots fade as he grew.

WastesBefore we moved to the woods we also took toilets, sinks, washing machines, garbage disposals and the weekly trash pick-up for granted. Living in the forest changed all that.

I drew the line when it came to an outhouse. There was no way I was going to leave my warm house on a cold night. So we bought a porta-potty. At first I dutifully used the little blue packets that came with it, but then I stopped and looked carefully at the ingredients. Did I want to pour powerful chemicals into our land year after year? No. So we used nothing, and instead of burying the wastes in a deep hole we fertilized an unused field by digging 6 inch deep trenches, and in our climate the decomposition is rapid and safe.

All the kitchen scraps go to the compost pile which the birds and chipmunks love to steal from. Water from dish-washing, baths and laundry is used in the garden.

ElectricityWe once asked the electric company how much it would cost to get a line put in, and at $3.50 a foot for 5 miles the bill would have come to $80,000! Obviously we had to think up an alternative.

Our first step was to buy a 2,000-watt generator. It was essential for running the power tools we needed in our woodworking business, and I would use it for a few minutes a week for food processing, but we didn’t want to use it for our daily needs because it is noisy, produces fumes and would soon break down under constant use.

For lights we use dual-mantle lanterns fueled by propane. They produce a fine quality bright white light that is excellent for reading. There are no fumes and little maintenance. We use a 12-volt battery for small things like radios, and when the battery used to run down we would either attach it to our battery charger run by the generator or put it in the car during a trip to town. But in 1986 we arrived at a more elegant solution for our electrical needs. We bought a solar panel which makes electricity directly from sunlight. We store the electricity in a deep-cycle battery, and the battery is connected to a 300-watt inverter that produces normal 120-volt AC current which we use to run small items like our sewing machine and electric typewriter. In short, we have become our own Forest Electric Company.

TelephoneWe have no telephone, either. We occasionally use a phone in town, but it was surprisingly easy to adjust to not having one. No longer would I jump when it rang or have dinner or some other activity interrupted by a phone call. Instead of picking up the phone we rediscovered the art of letter-writing. When it is important to get a message through quickly we use a CB radio.

MailThere is naturally no postman coming to our door each day, so we collect our mail in town every week or two. But is this really a disadvantage? When we open our post office box it is packed. There are flyers, advertisements, letters from friends, newspapers, packages, catalogs, books, magazines, letters from the kids’ pen pals, junk mail and brightly stamped envelopes from foreign lands, in short, a treasure trove with something for everyone.

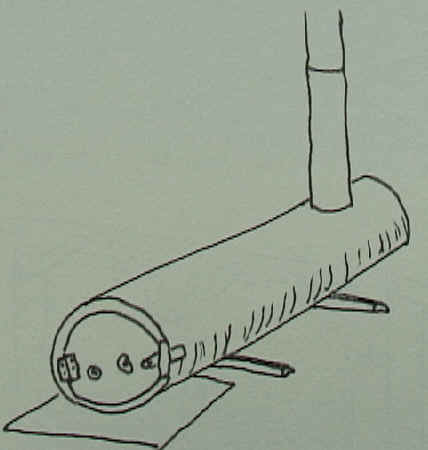

| Heat Our only source of heat besides the sun is wood, and like everything else having to do with living in the forest we knew nothing about wood stoves, chain saws and all the ins and outs of staying warm with fuel you collect yourself. During our first year we used a small Jøtul cook stove, and it not only kept us warm but I cooked on it, as well. Gradually as our confidence and experience grew we began to try our hand at making our own wood stoves. The result: a wood stove that heats the house quickly, toasts 16 pieces of bread at one time and costs $1.00. We made it from a discarded hot-water tank gleaned from the local dump. |

|

We took the cover and insulation off the tank, laid it on its side, cut a round door in one end and hinged it, and cut a 6 inch circle on the top for the stove pipe. The result is a superior chimney effect, which means that the fire started near the door is automatically drawn toward the rear of the tank where the stove pipe is. If you get the hot-water tank for free, the dollar is for the saber saw blades you might break as you cut the openings. This stove can be made air-tight simply by putting a piece of heavy-duty aluminum foil in the door as we close it, and it has the added advantage of using longer pieces of wood. We always take the precaution of starting a hot fire in our newly made stoves outside before we bring them into the house because we want to burn off any coating the tank may have that could give off unhealthy fumes.

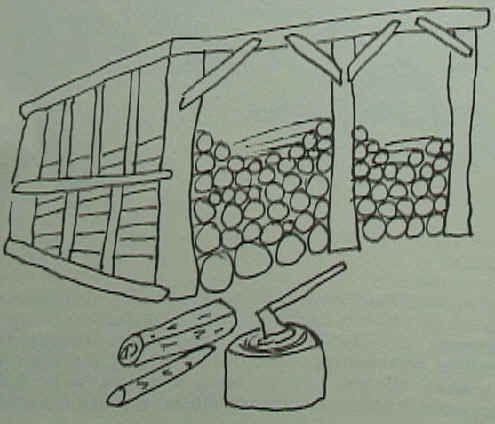

WoodWe are wood-rich here in the forest, and over the years we have explored many different ways of gathering our fuel supply. These have ranged from breaking sticks over stumps and cutting branches with bow saws all the way to using a decent and properly sharpened chain saw which slices through substantial logs with ease. It is one of our ongoing projects to gradually fill our wood sheds before the first snows come.

| But what really is wood? It’s the whole family jumping in the truck on some beautiful summer day and collecting a load of it. It’s the solid thunk of the rounds as we throw them in the woodshed, knowing that we are storing up real wealth for the winter to come. It’s the sharp thwack of the maul that smoothly cleaves them. It’s the incense of pine pitch. It’s the crackle and roar of a newly-built fire on a frosty winter morning that invites the children to stick their noses out of their beds. It’s the tingling of cold toes warming over the fire after a long ski in the woods. Staying warm becomes an adventure that draws us closer to the land, the trees and the winter itself. |  |

Water, electricity, telephone, fuel, and even getting our mail at first appeared to be problems that threatened our standard of living, but after confronting each difficulty we ended up not only surviving but thriving. Water comes to us from the sky, feeds our gardens, encourages a delightful assortment of wild life, and feeds our spirits, as well. Electricity brings us into direct contact with the sun, a lack of a telephone fosters the art of letter-writing, and so each basic in its own way teaches us a valuable lesson beyond itself, and the more we lived on the land the more we began to realize that these lessons are the true gifts of the simple life.

Neighbors and CommunityWhen we first moved to the forest there were three other families in about 100 square miles of forest. One couple lived about ¼ mile away but soon moved. The second who lived 1½ miles away was an older couple who had been born in the county. He drove a log truck and kept a road open in the winter. And the third family lived 5 miles away and had kids ours could play with. The population of this little forest community slowly increased until there were 7 or 8 families. At one point we would be seeing our neighbors practically every day, either at our place or theirs, or encountering them on one of the forest roads where we would stop and visit.

CHAPTER 5 THE BIOSHELTER

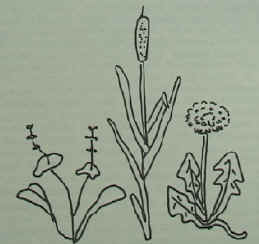

We had been living in our pole house for only a short time when we began to think about yet another basic: food. We tried to learn about the wild edibles of the area, and looked up old reports on the food plants of the early Indians and turned to modern plant books, as well.

| Wild strawberries, plums, elderberries dock, miner’s lettuce, choke cherries, service berries, watercress and cattails all became reasons for day trips to local streams and meadows. We ate them on the spot, canned them and dried them. The excitement of discovery kept us going for quite a time, and it was fun to pick dandelion leaves just outside the grocery store in town, leaves that were far fresher and more nutritious than anything offered for sale inside. We eagerly looked for morel mushrooms in the spring and treated ourselves to a week or two of sumptuous mushroom feasts. |

|

But what we really wanted was a garden. Local opinion was discouraging: "You can’t grow anything here. It’s too cold, the summer’s too short, you can have frosts at any time and the soil’s no good. Don’t even try." And everything they said was true, for we were living at an elevation of 5,000 feet with just the water that was in our tiny ponds, and the top soil, if you could find it, was about 1/8 inch thick. But we were determined to try.

The $20 Lettuce SandwichWe thought back on our sole gardening experiment. While still in the city we tried a miniature hydroponic garden. From what we had read you could grow a garden in gravel and feed the plants a chemically-balanced diet dissolved in water. The results were supposed to be fantastic.

So we bought lumber to make a 4 feet x 4 feet box, we lined the box with plastic, filled it with gravel, ordered the special plant food, rigged up the appropriate water-cycling system to feed the plants, sat back and waited for the harvest. The bill came to $20.

Everything went fine for the first few weeks. The seeds sprouted and began to grow. And then one day I looked out at our garden with horror. It was a hot day, a huge dog was thirsty and there was water somewhere down at the bottom of our box. By the time I saw him he had managed to dig an enormous crater right in the middle of it. I chased him off, but only two little lettuce plants had survived the onslaught. We sadly and ceremoniously cut them and put them between two pieces of bread. Hence, our $20 Lettuce Sandwich.

But we decided to try again. The nearest dog was miles away and we certainly couldn’t do any worse than the first time. We lined up a row of plastic containers along our large south-facing windows and soon had our very first garden. But it merely whetted our appetite. We needed more space, and we were getting the yearning to feel our hands in the rich, dark soil of an organic garden.

Our first step was to build an experimental greenhouse attached to the south side of our house and cover it with clear plastic. The results: the little seedlings that we had carefully started inside fried during the day, froze during the night, and the few that survived were eaten by chipmunks. Not too encouraging. This business of growing plants was more complicated than we thought. But we were determined to have a garden, and little did we know what this one desire would lead to.

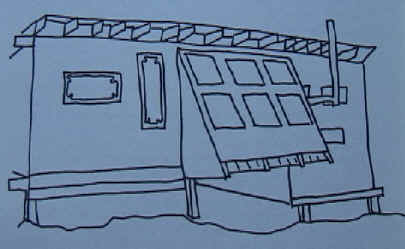

Even More NeedsThe answer was a real greenhouse, but the more we thought about it the more involved it became. Why not combine it with an indoor workshop? Since we didn’t have a refrigerator, why not include an old-fashioned root cellar? And a store room? And a harvest kitchen? And a place where guests could spend the night? By this time we realized that this would be no mere add-on to our little house. It would have to be a separate building entirely. The ideas kept coming. Why not make it an earth-sheltered building which would be warmer in winter and cooler in summer? The new building would produce a new roof which could be used for filling another pool, which would then water the plants in the greenhouse.

Then all the ideas came into focus. We would have not only an earth-sheltered building, meaning that dirt would go up as far as the roof line on three sides, but it would be a bioshelter. A house keeps you warm and dry. An earth-sheltered house keeps you warm and dry, but uses less fuel to accomplish it. But a bioshelter keeps you warm and dry, feeds you via the greenhouse, collects water, captures the heat of the sun and stores it in the earth around it and the water inside it. A bioshelter is organic. It is alive, it works for you and responds not only to the different hours of the day and night, but to the seasons, as well.

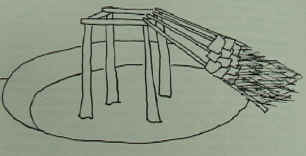

| We were asking a lot of this building, but surprisingly our inspiration was close at hand. The local Klamath Indians used to build earth-sheltered lodges for their winter living, and we took a close look at how they had been constructed. They had dug a 3' or 4' deep round or oval pit, put four poles upright near the center of it in the form of a square, topped them with beams, laid smaller poles from that square to the top of their pit, covered their poles with mats and bark, and then covered it all with dirt. Their entrance was from the middle of the roof, which also served as a smoke hole. |  |

Once again we walked around our land armed with compass, protractor and level. We played the game of design by digging little holes in the ground, arranging sticks that became beams and rafters, and seeing where the sun came into our miniature dwelling. Should we have a round greenhouse? Should we put the greenhouse on top of the guest room so that the rising heat would keep the plants warmer? But what would it feel like to live underground with all that dirt over you? And what of the water draining from the plants? Questions, questions, questions. We finally ended up with another, even larger, rectangle. Most of the space was devoted to the greenhouse, allowing not only room for the plants, but water containers, as well, for storing some of the heat of the sun during the day and letting that heat slowly radiate out during the nighttime hours. The rest of the building was for a workshop, living area, and root cellar.

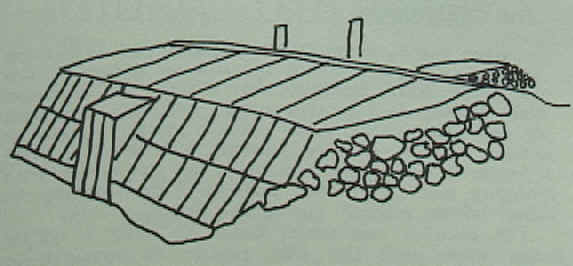

We hired a backhoe to scoop out tons of dirt and rock from the side of the hill and dig holes, for once again we wanted a pole house. We treated logs from the land, hoisted them into their appropriate holes, and heaved up the beams. "Watch out for your head!" "If you are going to drop it, yell first!" Once again it was just the two of us struggling against the force of gravity, and wondering just how this project was going to turn out. Our natural beams and poles from topped trees gave a rustic air to the place.

| Once the framing was up we nailed rough-sawn 2 inch x 8 inch planks from a local mill to the outer face to create the walls and roof. When they were in place we carefully put 6-mil black plastic on the outer face of the planks, and then had the backhoe come back again and gently push the dirt against the plastic until the earth was as close to the roof line as the lay of the land permitted. |  |

Sawdust and wood chips became insulation for the roof, and we covered them with sheets of corrugated metal. The front of the building was clad with fiberglass and salvaged window panes. After weeks and weeks of work, stretched over several years, we had a 1,500 square foot shell that had cost $2,500.

Our initial idea was to have the entire area open. We would try living in the back and the plants would have the front. It would be lovely (we thought) to live in an indoor garden. But the temperature swings that the plants could tolerate were uncomfortable for us. We stubbornly held out until the fall, but when we found ourselves huddled around the wood stove wrapped in blankets after dinner, we began to wonder.

And then came the night of the Freight Train Wind. Every fall we seem to get it, and that year it came at 11 p.m. The children were asleep snuggled in their sleeping bags, but we had our eyes wide open, listening to it gathering its strength across the forest. We could hear it roaring for miles, and then it was on us. It hit, and hit again. Suddenly we heard a wild ripping sound, and an open space appeared just over our heads where the greenhouse roof used to be. That did it! We shook the kids awake (how do they sleep through it all?), stumbled up the path to the top house, started a fire in the wood stove and went peacefully to sleep. The next morning we found 100 square feet of greenhouse roof sitting in our back field. We still had a lot to learn.

The GreenhouseWhen our bioshelter shell was done the first thing we had to do was create the soil we needed before we could start planting. We brought in truckload after truckload of rotted manure and hay, and when we saw that plants would actually grow, we got so excited that we kept on planting and ended up with a jungle. It was a beautiful sight, but the plants were crowding each other out and we kept stepping on them. But we actually got to eat them.

| The solution was raised beds. We built

3½ feet x 8 feet boxes, lined each box with plastic to conserve as much water as

possible, filled them with our newly made soil, and left an aisle 14 inches between each

box. The raised beds were a great improvement aesthetically and our food production

increased, for not only did the soil remain uncompacted, but each plant received extra

pampering and care. For the first few years each spring brought new ideas. We experimented with glass, vinyl, fiberglass and no glazing at all, for we were concerned that the plants would get as much of the full spectrum of sunlight as possible. We tried growing dozens of different kinds of plants from the old standbys of lettuce, tomatoes and squash to a bewildering variety of Chinese greens. We mulched deeply to save water and stress on the plants, fed the soil with rock phosphate, greensand, wood ash, dolomite limestone, a sprinkle of blood meal and a drink of fish emulsion. And we fought off the mice, pack rats, chipmunks, squirrels and rabbits who wanted to help us eat them. We were finally gardeners. |

|

When the first serious snow fall comes we cover all the fiberglass roof panels with sheets of plywood, and we double-line the greenhouse with plastic for a little extra protection against the cold. Soon the snow turns the building into a smooth white contoured mound blending into the hillside except for the south wall and doorway. Inside, though, it is an oasis of green that provides us with salads, mostly from the leaves of the older mature plants, during part of the winter.

Mad InventorsWhen we first built the bioshelter we thought it would be a clever idea to have the rain from the gutter system come into the bioshelter, filling a central pool and making it handy to water the plants. So we rigged up a gutter and hung it from the ceiling of what was then our living room. (You’re right. It was not too elegant.) We directed it so that the water would fill a plastic-lined hole in the greenhouse area. But then it rained. In the middle of the night. Once more we shot bolt-upright, grabbed our flashlights, and ran to the pool. The water was shooting down the gutter and into the pool like it was supposed to, but it was just about to overflow, Quick! Grab a shovel! Hold the flashlight! And with one eye on our pool and the other on the spot next to it, we dug like crazy. Just as we put a new piece of plastic in our new hole, the first pool overflowed and went into the new one. Another disaster averted! And so, soaking wet, with mud on our faces and clothes, and bone weary, off to bed again. Why don’t these things ever happen during the day?

Not wanting to go through the trauma of sudden rain storms ending on our bioshelter floor, we dismantled the gutter in our living room and rethought the water storage problem. Our next experiment was to build a round tank out of welded wire 4 feet high. We placed tar paper inside the welded wire and then lined the whole tank with black plastic. It wasn’t much to look at, but we happily poured gallons and gallons of water into it. As the water level rose we began to feel uneasy because there seemed to be a lot of strain on the wire. But when nothing happened we assumed everything was O.K. And then one day while I was standing next to it, it came apart in a roaring flood! Back to the drawing boards. Eventually, however, we assembled a collection of barrels, hot-water tanks and stock tanks that provide more than 1,000 gallons that moderate the greenhouse temperatures.

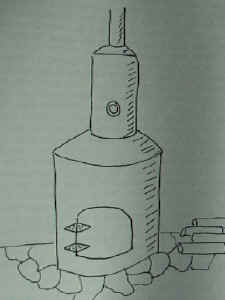

| More Inventions We thought it would be nice to have an open Indian-style fire pit in the center of our bioshelter, so we fashioned a metal cone, complete with stove pipe, and built our first fire. Results? The smoke cheerfully poured out into the room. Then, since we had had good luck with converting hot-water tanks into wood stoves we decided to try to make a fireview one. We finally ended up with a fat tank in an upright position with a large, hinged door, topped with a thin tank, followed by the stove pipe. |

|

Our bioshelter was a large building and we wanted a wood stove that would produce a lot of heat. In a moment of special inspiration we decided that if one tank stove worked so well, two tanks welded end-to-end forming an 8 feet wood stove would be even better. And so we constructed the Super Bomb and fired it off. The first thing that happened was that the pillar nearest it started to smoke, and a plastic bucket three feet away suddenly melted. Help! What have we done? We didn’t need that much heat.

But it worked so well that we had to channel all that heat. We built a metal rack to fit over it and placed on it a 3 feet x 8 feet stock tank 2 feet high that held 300 gallons of water. This time the result was a hot tub. We put rocks and dirt along the sides of the new stove to prevent any more pillars from smoking, and in a very few hours the temperature of the water was over 100 degrees. The kids loved it.

You would have thought we would have stopped here and gone to read a book or take a nap under a tree, but we had one more stove to make, an underwater one that could be plunged right into the water tank itself. We figured that the water would heat up much quicker that way. So once again we took another hot-water tank (the dump was beginning to look a little bare), put it on its side, plugged up all the holes, and with the help of our welder friends cut a rectangle on the top, attached a metal box and door, and cut a hole for the stove pipe whose first section was made of welded 6 inch pipe.

Everything seemed fine until we started filling the stock tank with water. Suddenly we heard a large clunk and to our shock we saw that the heavy metal stove was floating! We put huge chunks of metal in it, and it still floated. All four of us stood on it and it still didn’t sink. So we ended up building a wooden rack to put over it and tied the whole thing down.

The Inner RoomWhen we realized we would not be able to live comfortably with the temperature swings plants didn’t mind, we built an inner room with a glass wall that would thermally shut us off from the greenhouse but visually would still keep us in touch with it. Its north wall is covered with books from floor to ceiling, it is ideal for summer meals, and it is a perfect place for overnight guests.

We no longer try to live there in the cold weather. Earth-sheltering does not do away with the need for insulation, for in our area the earth temperature is 47 degrees, and though that is better than the air temperature, it makes the building hard to keep comfortable. To make it into a year-round dwelling we would have to thoroughly insulate it.

The Root CellarBehind the inner room deep in the hillside is an 8 feet x 16 feet root cellar. It is our secret weapon for winter when we are snowed in and must travel by skis. In it is a 6-month supply of food: rows of canned goods, jars and bottles, barrels of grain and soybeans, jugs of oil and peanut butter, and sacks of potatoes, carrots and onions. Every evening before dinner one of us goes down to the bioshelter to pick a few greens for the salad, and grabs a carrot and something from our stockpile. These daily shopping trips make me feel rich in a deeply satisfying way.

Why Bother?Why have we put up with so many problems with our bioshelter? Why are we still changing it as the seasons go by and show us yet another possible improvement? Because it is a vessel that brings us closer to the earth. It is good to grow some of our own food, and it is healthy for us to make daily and seasonal adjustments.

Every day brings its chores, and even its problems, but one of the beauties of living out here is that we are free to face those problems and try to solve them. If one solution doesn’t work, then we try another. We don’t have to do it right the first time. We don’t even have to do it right this year. There is always next year. There is no one way of doing things. One solution may work for a while, and then we dream up another one, usually better, and all the while we gain self-confidence. We don’t have to freeze in panic when something doesn’t work. Each year of living in the forest has been a gift, it has been a special time of going, not into the past and into primitiveness, but forward and discovering new ways of living, new parts of ourselves, new talents, and hopefully, new patience with both ourselves and the very environment we live in.

To struggle with the bioshelter, to tear down walls and build them up again in new ways, to reconsider what the roof should be like, to watch what happens to the plants in winter, to be concerned about the sun angles and water tanks, to fix gutter systems and change pool sites, to haul in even more truckloads of manure, or mountains of hay for mulching, is to live alive. The sun and wind and sky become an active part of our consciousness, and we become aware of the forest and the animals, large and small, that share it with us. We are part of life, and to live in the forest is to wake up our awareness of that simple fact, and it is worth all the hassles and mistakes to discover it.