San Luis Gonzaga today

Guaycuran mother and child

Mission San José del Cabo in 1769

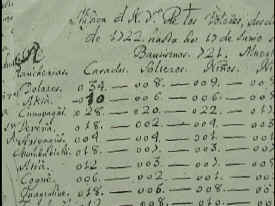

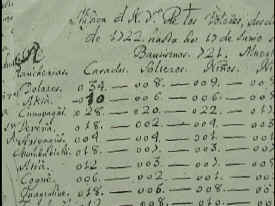

Guillén Informe of 1730

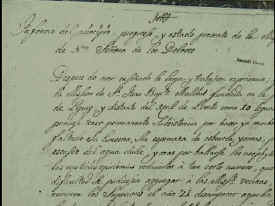

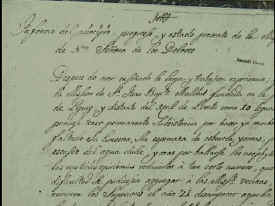

Guillén Informe of 1744

La Pasión in 1950

San Luis Gonzaga today |

Guaycuran mother and child |

||

Mission San José del Cabo in 1769 |

Guillén Informe of 1730 |

||

Guillén Informe of 1744 |

La Pasión in 1950 |

| Lamberto Hostell Lamberto Hostell was born on Oct. 18 , 1706 in Bad Münster-Eifel near Bonn in the lower Rhineland Dutchy of Jülich.1 He joined the Jesuits at Trier on his 19th birthday and finished his theological studies at the Colegio Máximo de San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City in early summer, 1737. Before the end of the year he had arrived in Baja California. His exit documents from Spain described him as of "average physique, fair-skinned, blue-eyed, blond hair, beard."2He was assigned to establish the new mission among the Guaycuras and went to Los Dolores to learn the language and help Clemente Guillén who , Hostell tells us, "was on the verge of collapse under the weight of his apostolic tasks."3 Hostell writes of the country and its people, in a letter to his father: "The land is wild, rough, dry and utterly unproductive. The inhabitants are savage and barbaric tribes, similar to other humans in outward appearance (except for their chestnut-brown complexion and pierced noses and ears). Because of their primitive habits, however, they deserve to rank below animals rather than be considered equal to other humans."4 He tells us in this same letter that within a year some of the Indians who were to become the founders of San Luis Gonzaga mission received baptism, and that he would have actually begun building the new mission had he not had to accompany the Father Vice Provincial on his travels, and then take care of the mission of San José for two years. "Finally, in the year 1740, I began to work with such success that I brought together 700 Guaycuros in three settlements, namely, San Luis Gonzaga, San Juan Nepomuceno, and Santa María Magdalena. This coming October I shall attempt to find out whether two pagan tribes, the Ikas and the Huchipoies, are ready to receive the gospel and are willing to accompany me westward to the village which would be the fourth established by me. I have many reasons to be optimistic in their regard."5Although Hostell was assigned to create the new mission of San Luis Gonzaga in 1737 , he was away at San José from August 1738 to November 1740.6 The mission was sited at Chiriyaki, a place well known to Guillén from his earlier journeys of exploration. Hostell describes it in his informe of 1744: "The weather is quite hot in summer and temperate the rest of the year. It has a very small but ever-flowing spring of water which irrigates some lands covered with reed-grass and also this farm which has been cleared and cultivated. Until now it has not yielded more than 25 fanegas of corn and 10 of wheat. It is not known whether it will produce more in the future. At any rate the recent rains which have been more copious than usual created a torrent which carried away the cultivated soil and left the rocks of the arroyo where the plot of land was situated. Thanks be to God, Who wished this to happen; and, if He so wishes, can easily remedy it." 7We can piece together some idea of Padre Lamberto ’s missionary activity among the Guaycuras.1737. He converts several adults who go to the mission of Los Dolores at Apaté , an incident he had already referred to in his letter to his father.1738. Hostell goes on an expedition into the mountains of the north , "and a fairly large number of pagan families were thoroughly instructed and received holy baptism."8San Javier is thrown into turmoil by rumors that the Guaycuras of Los Dolores are plotting to come and kill the padre and sack the mission. Soldiers investigate but can find no basis for these stories.9 1739. Hostell is away , but Guillén brings over "to the mountains of the west a considerable group of pagans of the Bay of Santa María Magdalena; they were baptized at a spot called El Espíritu Santo. In 1740 others came to be converted at Apaté."10 The mountains to the west probably refer to the mountains of Chiyá, and so Espíritu Santo was probably located in the Chiyá area.Guillén writes three letters (April , May, and September) to the procurator of California Ignacio María Nápoli about a canoe that Nápoli and Jaime Bravo have helped him acquire for Los Dolores. In the April letter he mentions he is instructing 29 adults at the ranchería of Tegacua on the Bay of the Magdalena. The September letter mentions a rumor of unrest among the Indians of San Luis Gonzaga.1741. Hostell has returned , and he goes "to the mountains in the west, to a site called Acheme, about 16 leagues from Apaté. About 80 pagans gathered, all coming here from the western coastal area. After thorough instruction lasting nearly 3 months, they were allowed to receive the holy Sacrament of baptism. In May of that same year the missionary went to the Bay of Santa María Magdalena and instructed there the poor old Indians, too blind and weak to be able to go to Acheme."11On July 21 , 1741 Hostell was in Loreto making his profession in the presence of Padre Guillén.12La Pasión The site of the mission of Los Dolores at Apaté had provided food for only 2 or 3 months out of the year , and Guillén was dependent on what could be purchased with the revenues from the founding grant, and on help from other California missions. Miguel del Barco comments that corn was sown in the first year, but from 1740 and for years before then there had been a small sowing of wheat which had been used to make hosts for the missionary, and the rest had been given to the Indians.13As Guillén gained experience , it had become clear that the mission really ought to be moved into the sierra, but this move was delayed by the rebellion in the South and the inclination of some of the Guaycuras closer to home to follow its example, as we saw. Guillén had also told us that at the beginning of his stay at Apaté the process of exploring the territory of the mission and converting the local bands could not quickly take place because of the mission’s lack of resources. But perhaps there was another reason, as well. In the list of missionary assignments kept by the Mexican province of the Jesuits, we read an entry for the year 1723 that has Guillén assigned to Guaymas on the west coast of the Mexican mainland.14 So it is possible that just as during his residence at Liguí, Guillén was absent for part of the early years of the founding of Los Dolores.The mission was finally moved 10 leagues into the sierra on Sept. 7 , 1741, the Vespers of the Nativity of Our Lady. It was now located at Tañuetiá, or the abode of the ducks, a location that had been already baptized La Pasión. And now all the attendant labor of building a new church and outbuildings had to be taken on again, Padre Clemente tells us, and all the supplies from Loreto had to be carried up the steep grade to the new mission site.We can assume that life at Los Dolores followed the usual mission pattern of Apaté and elsewhere in Baja California. The neophytes were fed when they stayed at the mission , and a good deal of the resources of the mission went into clothing them, as well. How, indeed, could they be good subjects of the King if the men went around naked, and the women nearly so? More of the mission’s resources were spent on the sick, the soldiers in the missionary’s escort, the ranch hands who took care of the mission’s herd, and so forth, and since food was so limited, the Indians only came in turns to stay at the mission, which probably amounted to one week a month at the new Los Dolores, and during the rest of the time they gathered their "herbs, roots, seeds, wild fruits and fished and hunted."15It was in 1741 , as well, that Guillén urged the Indians, who were still scattered in their rancherías, to group together in 6 pueblos, or visitas, at a comfortable distance from the mission so they could, no doubt, come in turn, or be visited more easily by him. And he gives us a valuable census of these pueblos: Los Dolores, itself, now at La Pasión, Immaculate Conception, Incarnation, Trinity, Redemption, and Resurrection, perhaps the Resurrection we met before. But we don’t know where any of these pueblos were located. He also gives us the figures for the new mission of San Luis Gonzaga which is comprised of: Bahía Santa María Magdalena, San Luis Gonzaga, San Juan Nepomuceno, Jesús María, and the West Coast. We will analyze the actual numbers later. He also found the climate in the sierra healthier than that of Apaté, for the heat weighed him down less both mentally and physically. From 1741 to 1743, he is once again padre visitador.

Miguel del Barco on La Pasión Miguel del Barco , himself a Jesuit missionary in Baja California and one of its earliest historians, writes: "Padre Clemente Guillén founded the mission of Nuestra Señora de Los Dolores on the beach at Apaté on the Gulf of California, which was the mission headquarters for two years until the Indians of this mission (which occupied a large territory) had been reduced and baptized, and then it was moved so that they could more easily and without the labor of going down to the beach would be able to come to the headquarters, to another place up in the sierra called Tañuetía in the language of the Indians… The only thing left to note is that at this same place from the first years of the mission it had carried the name of La Pasión del Señor. And since it is on the road from Loreto to the South, this site was very well known by the name of La Pasión. After, although the headquarters was moved to it, not withstanding, this name prevailed; the way it is usually referred to in California is not Los Dolores like the other missions, which are called after their patrons, but commonly it has retained the name La Pasión."16This move of Los Dolores after two years is not supported by any other historical evidence that I am aware of , and it appears to go against the informes of Guillén. Barco, himself, writing of the year of 1746, describes San Luis Gonzaga "as 7 leagues to the west of the headquarters of Los Dolores, established before this time in La Pasión, as I said above."17 It is not likely that this refers to a move that took place in 1723, i.e., two years after the founding at Apaté, but to the move of 1741, and somehow the manuscript ended up saying 2 instead of 20 years. Finally, Tañuetía, as Barco gives us the name, should probably be Tañuetiá, that is, accented on the last syllable like many of the Guaycura place names in the area.

Descripción y Toponimia One of the most valuable documents in terms of mission geography is Descripción y Toponimia Indígena de California.18 It carries no mention of its author, but someone has written 1740 on the top of the manuscript. Miguel León-Portilla, who published it in 1974, reasonably suggested that the author is a non-Jesuit from the way, for example, he writes: "padre lego" or " lay father" which is a contradiction in terms, instead of "hermano coadjutor," and its author may have even been the first captain of California, Esteban Rodríguez, for he was a person of wide knowledge of Baja California, and the author says that where he didn’t have direct experience, he learned from soldiers who did. And León-Portilla surmises that the illustrious Capitán might have written it at the request of Miguel Venegas , the Jesuit historian who was soliciting information for his Noticia de la California which he finished on Aug. 5, 1739. Therefore, the manuscript might have been written before 1740, or arrived after Venegas had finished his work, and it is true that Venegas apparently had access to a diary of Rodríguez. There is, however, internal evidence that indicates that these pages were written after Sept. 7, 1741, as we will see in a moment, and that makes it unlikely that it is a document solicited by Venegas, though it still may be the work of Rodríguez.The text , itself, is a description of the principle roads and places of Baja California with some indications of the original Indian names. We will restrict ourselves to our chosen area about which the author tells us that from La Paz to Dolores there is a road of 50 leagues, and this is an area populated by the gentile Pirús, or who are also known as the Piriuchas, or Guaicuras, and along the road there is a watering place in the arroyo of Los Reyes, and at Guadalupe which is another arroyo with carrizo from which you go to San Hilario, which is the largest arroyo and in which can be found a vein of flint of many colors. From there a road leads to the narrow arroyo where Las Liebres is to be found, along with sufficient water. 5 leagues after that we arrive at the very big arroyo of La Pasión which the natives call Chiyá.Then our author writes: "Here there is a new mission which before was Rancho Dolores… From La Pasión one goes to Dolores traveling 12 leagues in the middle of which is found at the side of the road (the right) San Juan which its inhabitants call Quaquiguí, a stopping place with water and people who receive their doctrine at Dolores. It does not have a church or a pueblo. Los Dolores maintains itself with only a somewhat small spring. It is little more than a league from the beach… The natives who dwell there are called the Apaté, and so they call the place. "From here one leaves for Loreto by the road along the beach some 10 leagues to arrive at San Carlos where there is water and a bed of pearl-bearing oysters. (placer de perla) Leaving the coast you ascend the sierra, and after 6 or 7 leagues arrive at an arroyo (the name of which in the language of the natives is … and I don’t remember) which flows to the other coast, and since it is on high land, flows, as well, to the east coast and joins the sea at the very big bay of Agua Verde. From this stopping place one goes to Santo Thomás by way of a very great ascent and descent, and arrives at an arroyo that has the same name and which is filled with water which drains towards the other coast; the country is very sterile and rocky. From here you go to San Hilarión, another arroyo with water, less inhospitable than the preceding one, but bad country not much good for anything. The arroyos are about 5 leagues from each other. "From this place you leave and descend to Liguí which is on the coast and was and is a mission, although without a father and with very few sons because they have been moved to Loreto. It is a population with cattle and horses and is some 6 leagues from San Hilarión."19Later he describes the various population centers and says of this area: "from this one (the mission of La Paz) to Chiyá (La Pasión it is called) is a land of gentiles, and the latter has many people under the care of the father minister. The natives of this nation are called Chiyás, and it has other rancherías that are located in the arroyo below and make up the number of people in this mission, which are many. There are many gentiles on the other coast, and from it begins the part that touches the jurisdiction of the presidio of Loreto. "Next is Los Dolores with which it shares a father (con que tiene padre) and administers the native ranchería and that of San Juan Cuaquigiú, that of San Carlos and others, which comprise a sufficient number of people."20 When describing the coast in the vicinity of the Islas de San Francisco and San José and Los Dolores, he mentions a San Hilario somewhere in the area.The 1740 date that appeared on the top of the manuscript was probably placed there by someone other than the author , and appears to be too early since we just saw how the text reads concerning La Pasión: "Here there is a new mission which before was rancho Dolores" which clearly seems to refer to the reestablishment of the mission of Los Dolores on Sept. 7, 1741 at La Pasión. If this is true it would make it unlikely that this was a document requested by Venegas who had finished his work more than two years before.It is interesting to note that our author tells us of a Gulf road going from Los Dolores 10 leagues to San Carlos , perhaps the road Guillén mentioned in his informe of 1730, and it is possible that traces of this road could be rediscovered today.It is worth looking at the manuscript of this document which has two parts, the first of which is what Miguel León-Portilla published. The whole of the first part appears to be written by the same person, but just before the last page the handwriting becomes more condensed at the words dividida la conquista en dos provincias. The change in handwriting appears to reflect the duality of this first part in which the geography of the missions is covered twice. The second unpublished part of the manuscript, written in the same hand, might well help to explain this duality, for it appears to be the original draft of the second section of the published manuscript, but what interests us is the fact that it contains some information about the populations of the missions not in the published version. It tells us that La Pasión has a Father minister with 200 people, more or less, in his care, and Los Dolores has a Father minister – a fact apparently altered in the final version – with some 300 people, and a visiting station at San Juan Quaquigué some 7 or perhaps 9 leagues away. 1742. Hostell tells us that several Indians were converted at La Pasión.21 The change from the conversions at Apaté to La Pasión indicate the transfer of the Mission of Los Dolores inland to its new location at Chiyá , or the arroyo of La Pasión.1743. Hostell searches out "several unconverted natives in the vast expanse of some 80 leagues along the west coast from the arroyo of Santa Rosalía, a spot beyond Mission San Javier, as far as the arroyo of La Pasión which empties into the Bay of La Magdalena, opposite the southern portion of the large island." Hostell "reached their homeland in October by following the arroyo of Cocloraki, which flows between the arroyos of Santa Rosalía to the north and of La Pasión in the south. Three and a half days of difficult traveling brought him successfully to Titapue. The route lay through a level area, it is true, but arid, thorny, and devoid of pasturage and fresh water. Because he reached the site on the feast of Saint Luke, it has been known ever since by the name of that evangelist. It is about 2 leagues from the beach. It has a very deep well of saltpetrous water, which is dipped out in jars and pans for the animals to drink."22This is the area of the Uchití , and the Ikas, the Añudeves and the natives from Ticudadei have joined them. They speak a language that is different from "Guaycuro," but are receptive to the Gospel and have been invited to La Pasión which they have come to several times since December of last year, and then baptized.While Hostell was at San Lucas he had to hear confessions at the bay. He went without drinking water for 24 hours until he reached the sands of Aburdebe. He returned by way of the arroyo of La Pasión , and by the beginning of November was back in Los Dolores. The natives are now at San Luis, San Juan Nepomuceno, and at Santa María Magdalena. The number of adults and children baptized from July 14, 1737 to the present, Sept. 28, 1744, is 488.To Hostell ’s mind, the rebellion of the Pericú in 1734, 1740, and 1741 has been counterbalanced by the conversion of the Guaycuras. They take care to make a worthy confession and receive communion frequently, and make efforts to better their way of life.23 The men go about naked, and the women wear aprons of palm leaves or woven rushes. He adds to the end of this 1744 report an edifying story of conversion. In May of 1741 he was at the Bay of Santa María Magdalena when a pregnant woman came to him and wanted to be baptized, but she needed more time to be prepared. He was afraid that after he departed she would kill her child, according to the universal custom of the tribe, and thus make its baptism impossible. He promised to offer to Our Lady the Mass to be said on the following Saturday if the child would be born before he left. The evening of the day upon which he made his promise the woman went into labor and the child was born the next morning, and baptized.

The Changing of the Guard The rough life at Los Dolores took an increasing toll on Guillén. Padre Sebastián de Sistíaga , writing on Sept. 19, 1743 to Padre Provincial Cristóbal de Escobar y Llamas from San Ignacio in his capacity as padre visitador, comments: "Father Clemente Guillén is now very old and very feeble, because of his many and continuous strenuous efforts and because of the many illnesses he has suffered. Hence, he is physically unable to take care of his mission. He writes to inform you about the state of his health so that you will dispatch someone here to take over the burden he can no longer carry. "Besides this urgent need, there is danger that Father Lambert Hostell fall ill and become incapacitated. He will have to take care of the difficult mission he has begun because Father Clemente can no longer do so. The latter, in mentioning how painful his illness is, adds that the land and searing climate aggravate the condition of his liver. His Reverence seems to be hinting that, since he can no longer attend to the duties of a missionary, he would gladly retire to a better climate. I think that Your Reverence in your charity should grant him this favor and send another here, bringing with him the authorization for Father Guillén to return to the Province."24Another source of information about San Luis and Los Dolores comes from the documentation generated by the visit of the Jesuit Visitador General Juan Antonio Baltasar: "Mission San Luis, on December 9, 1743. On visiting this mission, I learned that since 1743, when its more permanent status began, Father Lambert Hostell, its missionary, had in the account of its annual alms 4,381 p 2. This entire sum was spent on the upkeep of the missionary, the church and natives. Nothing is owed to the church; the mission owes to the Loreto treasury, at the close of the year, after the accounts were adjusted, only 49 p 6.5. It has two dependent stations of nomadic natives for a total of about 180 families. "Mission Los Dolores and La Pasión, on December 9, 1743. On visiting this mission, I learned that since 1740 Father Clemente Guillén, its present missionary, had to its credit from its annual alms the amount of 3,826 p 7.5. All of it was spent for the maintenance of the missionary, church and natives. No one owes the mission anything; whereas the mission owes the Loreto treasury at the end of this year, according to the adjusted accounts, 15 p 1. "Possessions: some cows, a few goats, a team, a small irrigated field, a diminutive vineyard, and a canoe. "In its territory there are 8 settlements (bearing the names of several saints) numbering about 200 families."25These reports are augmented by Baltasar ’s 1744 general report on the missionaries. "Father Clemente Guillén is a venerable old man. The very sight of him inspires respect for him. He is working in a very poor mission. His health is broken; his vision is gone. I think that it would be most appropriate for Your Reverence to write him expressing the gratitude he deserves for his work and devotion, and offer him the consolation of retiring to the school of his choice, where he can get well and continue to live. In his present mission, he can not move a step, and the missionary assigned to assist him is very busy in taking care of Guillén’s mission, his own, and a third one he has just begun. You might add in your letter, if you so care, that in case he can not go to a school he may retire to Loreto, which has comfortable living quarters. Here he could be taken care of without any responsibility on his part of administration. But you must add that this is not just an offer but a command, so that he will choose what he realizes is best for his health and strength. Otherwise, if the choice is left to him, he will perhaps choose what is most difficult. Such a choice would not be to the advantage of the good administration of that mission of Los Dolores of the South. "Father Lambert Hostell, who has been Guillén’s companion for the last several years, is among the best, most virtuous and capable ministers in our missions. He has put up with Guillén’s whims and is doing the work of many men. Besides carrying the burden of Mission Los Dolores, he takes care of the nomadic natives of Mission San Luis. And on the Bay of Magdalena which opens into the Pacific Ocean, he has begun a third mission …"26 Baltasar also singles out Guillén and Hostell, among others, as being eminent linguists.

Guillén ’s 1744 ReportGuillén , himself, in his informe of 1744 tells us that the Indians, without force, or material inducements, have listened to the call of the Gospel. They have put aside their superstitions and diabolical instruments like capes made out of human hair and tablets, and have given up polygamy and the sacrifice of their first-born, as well as their continual discords and wars, and now practice the exercises of Christian piety as if they had been raised in the faith, that is, they hear Mass, recite Christian doctrine morning and evening, confess their sins each year and before marriage, and not a few of them do so, as well, before the principle feasts of the year. They received the sacraments when in danger of death. The text continues, rather strangely to those accustomed to modern Catholic eucharistic practices, to tell us that the Indians have not received Viaticum, that is, the Eucharist at the time of death, because Guillén had not found them capable of it.27The trials of Guillén ’s ministry, he tells us, were due to the roughness of the land, the poverty of the mission, the rude and small capacity of the natives, and the sheer physical difficulty in contacting them. He had to "search them out in the caves, peaks and mountains, and to speak to them almost one by one, and in this way to learn with great care their uncultured language, different from all the other California languages, and teach various ones Spanish in order that they could be teachers and interpreters." This he did, he tells us, at the price of his health. But Guillén was left with the consolation of having populated heaven with the souls of many children who died soon after being baptized, and "flew to glory." And there were adults, as well, to which he attributed a high degree of probability that they, too, had gone to heaven. Guillén tells us, for example, that a catechumen in 1743 suddenly got sick, was baptized and died in the grace of God. These and other graces he felt came through the intercession of Our Lady of Sorrows. In 1744, for example, during the novena before the feast of the Assumption of Our Lady on August 15, there was such an abundance of rain that there was pasture for the animals and a harvest of seeds for the Indians, the like of which hadn’t been seen in past years. This, incidentally, gives us a glimpse into how close to the bone the resources of this mission were.Two points in these informes of Guillén and Hostell require comment. If Guillén cannot see , he cannot have written his 1744 report himself, and even some of the phraseology strikes the ear differently with its author referring to Guillén in the third person, i.e., "the known zeal of P. Clemente Guillén." Instead of being signed Clemente + Guillén like the one of 1730, it reads, "now in charge of this mission is P. Clemente Guillén." The most likely candidate for the actual author is Lamberto Hostell, perhaps writing it together with Guillén. Hostell in his own informe writes concerning San Luis Gonzaga and its mission stations: "I have given their statistics in the account of the mission of Los Dolores…"28 When we compare the handwriting of Guillén’s 1730 report to his 1744 one, we see that they were, in fact, written by different people.The second point has to do with the proposed west coast mission of La Santíssima Trinidad. Despite Hostell ’s high hopes, it never developed. Miguel del Barco in his own informe of March 1744 writing about San Javier, tells us "in the west along the beach of the sea lives some few families of the Guaycura nation which will be collected at the new mission which is to be founded between other people of the same language almost south of this mission, and in between it and that of San Luis.29Without the new mission , the west coast Guaycuras drifted north and east to San José de Comondú. From 1744 to 1762, and especially after 1752, Crosby estimates 200 Guaycuras arrived at San José. If earlier in 1730 a soldier had been stationed at San Miguel de Comondú to ward off their depredations, now they were welcomed to supply labor for the fields left underutilized by the decline of the Cochimí. 1752 saw the baptism of the son of Rosalía , a Guaycura whose deceased husband had fled San Luis Gonzaga. Perhaps he didn’t care for the new regime of Jacobo Baegert that we will see in a moment. 1753 saw the baptism of the son of Miguel Carrillo, "Capitán de los Waicuros," and Antonía, his wife. This influx of the more uncouth Guaycura somewhat disconcerted the missionary of San José, Francisco Inama: "The latter tribe, recently converted, came to us here from the coastal lands along the Pacific Ocean. They keep me busy because of their ways, which are still rather savage. They are accustomed to sleep on the sand under the open sky, and it has cost me no little effort to get them to live in a hut. In order to protect their sick from sun and wind, I had them brought under a roof; but this proved a source of greater suffering than the illness itself. "If a horse or mule, overburdened by its load, died, they would enthusiastically plunge in and devour the carrion, utterly disregarding all my sermons against such a disgusting habit. They are now, however, approaching a better way of life."30Inama , somewhat new to the Spanish language, following the rule that if a neophyte died without the last rites a written explanation had to be given,31 described the death of the Guaycura Juan Peraza "…habiéndose acostado bueno, amaneció muerto," that is, "because having gone to bed well, he awoke dead."32By 1746 Guillén finally retired from Los Dolores and was officially replaced by Lamberto Hostell. He went to Loreto where he helped hear confessions and filled in when the missionary was away , and he also made use of his talent for languages by learning a new one in order to instruct and hear the confession of an old Indian woman who had come to Loreto where no one was able to understand her language, and was unable to return to her own land. And Barco adds a curious line that Guillén had had no particular inclination for the remote Indian missions.33 A little late for that. Guillén died in 1748 and was buried at the church in Loreto.34The modern Jesuit historian , Ernest Burrus, places Padre Gaspar Trujillo at Los Dolores for a short while in 1748 during this transitional period, probably on the basis of Jesuit missionary assignment records.35Juan Javier Bischoff Hostell ’s move to Los Dolores left an opening at San Luis Gonzaga which was filled by Joann Xaver Bischoff. Bischoff had been born in Glatz, Bohemia in 1710 and had entered the Company of Jesus in 1727, and came to work in Baja California in 1746.36 His exit papers from Spain described him as being of "small stature, fair skinned, blond, blue eyed, thin beard."37 At San Luis he built a house and church out of adobe and remained there until 1750, after which he went on to serve in other Baja California missions.38 Baegert tells us that Bischoff was still converting Indians in 1748.39 Bischoff was also known to train the Indians in choral singing, like Padre Pedro Nascimben, who once averted the punishment of his Indians by having them greet the padre visitador with beautiful singing, and so it is possible that his little church in San Luis rang with litanies.401750s The best source of information on Los Dolores in the 1750s is Hostell ’s second letter to his father, and the account of the mission he sent to his fellow Jesuit, Josef Burscheid, both written on January 17, 1758.41Hostell writes to his father , "contrary to my hopes, the mission of La Santíssima Trinidad, about which I wrote to my devoted sister, could not be established for lack of provisions and funds." He has given over to Bischoff the mission of San Luis, having taken care of it himself since 1746, along with Los Dolores from where he is writing this letter. Los Dolores is 5 hours away from San Luis. "Twelve hours from here I have a plot of productive land where I discovered a small well. I have planted some wheat and corn in the hope of eventually saving me and my Indians from having to endure such acute hunger as in the past." The Indians grasp the meaning of the Gospel more readily than those in other areas. "They are deeply interested in their eternal salvation and, except for a few light-headed individuals, persevere steadfastly in their faith. This they profess not merely by word of mouth, but also by their edifying conduct."42 All told, he has baptized 2,000 and brought the people he had assembled for La Santíssima Trinidad to Los Dolores, at least some of them. Others were distributed in the other missions.Particularly interesting is Hostell ’s report to Father Josef Burscheid of the same order and province. "The land itself is so rough, dry, stoney, and thorny, so wild and sterile that, despite all our diligence, it does not furnish us with sufficient sustenance." But Hostell says that there had been an abundant harvest of souls, and he has always enjoyed good health. His native charges "easily and quickly understood the truths of our holy Christian faith and fulfilled their duties diligently and exactly." Their conversion was easier because they had no formal idolatry. "They had no temples with idols, no images of their gods, no worship of idols. In their entire vocabulary they did not even have a word to express God or a divinity; we are obliged to use the Spanish word Dios."43 "In the beginning, we missionaries were of the opinion that they paid homage, as though to idols, to certain small wands, the tip of which contains the image of a savage or bearded man; but the natives corrected our wrong interpretation, and informed us that they used these staffs merely to heighten their mirth on days of feasting and rejoicing. They call these wands "Tiyeicha" in their language, which means "He can talk." I thought that perchance the infernal spirit participated in their celebrations and even spoke to them through such objects; but they assured me that they have no dealings with the enemy of their souls, and that they have neither seen him at any time nor heard him speak."

"Among their most solemn days of celebration is that on which they pierce the extremities of their children’s ears and noses. After having their sons and daughters prepare themselves for this event through three days of fasting, on the fourth they all gather, especially their conjurers who convene in large numbers, all attired in capes woven from human hair. They carry in their hands the aforementioned wands, also the small tablets into which they have scratched some rude figure(s) with a sharpened stone, used instead of a chisel or knife. Such figures have no idolatrous or superstitious meaning. They adorn themselves in the finery mentioned, but which as Christians they completely put aside and also throw away without reluctance their wands and tablets."44 The pregnant women practiced abortion whenever they had eaten meat slain by a lion or wildcat, and mothers strangled their newborn "in order to preserve its life or form." The 14 missions contain slightly more than 6,000 people, and, "My Guaycuro Indians alone make use of 4 different dialects. The same is also true of other missions. As a matter of fact, it not rarely happens that in one household the husband speaks one language and the wife another. Our older missionaries attribute this linguistic diversity to the fact that new groups of natives repeatedly descended from the north, bringing with them these different languages."45 In 1759 another brutal murder galvanized mission Los Dolores. Since the mission had few fields, and those it had were very distant, and so weren’t of much benefit, Barco tells us it received alms from other missions, as well as maintained itself by buying supplies with its annual mission funds. To receive these supplies it had a big canoe whose arráez, or captain, was an Indian from Ahome in Sinoloa called Vicente. Vicente got along well with both the missionary and the Indians, but one day returning from the south with 10 or 12 Indian rowers, they put in to land either because of bad weather, or to rest, and Vicente tried to break up a fight between two of the Indians. One of them turned on him and began throwing stones at him, and finally killed him. The Indians, because of their fear of punishment, hid his body, broke the canoe into pieces, and threw the mast and some of the sails in the water near a cliff. They went back to the mission and pretended they had been shipwrecked. But eventually the truth came out, the Indian who had killed Vicente was executed, and the rest punished. Padre Hostell did not have the heart to try to acquire another canoe, and perhaps faced similar problems, and so he brought in all the supplies after that by pack trains. This took 6 days from Loreto, and 8 or 10 days from San José in Comondú.46 Jacobo Baegert, writing in September of 1761, tells us that this boat incident happened "last year," and gives us some additional facts. The boat was returning from San José del Cabo with meat, lard, raw sugar, corn and several dishes of Chinese porcelain. The murderer was shot, but the ringleader "escaped and spent the nights in the house of the missionary, a place of security and liberty, where he stayed three whole months," stealing fruit and seducing Indian girls with it.47 Baegert tells us this story in the context of the three murders that had taken place at Los Dolores since he was at San Luis. This was one of them, and another involved an 18-year-old boy who had served as a page of the missionary since childhood, committed adultery, and fearful of being reported, invited the husband to a game on Ascension Day, and knifed and beat him to death in the presence of a 14-year-old Spanish boy. Baegert insists that the Indians brought up in the mission from their youth are "the worst and most malicious."48 This leaves us with two questions. How could the Indian involved in the boat incident hang around the mission so long without being apprehended? Baegert points to the laxity of the soldiers and the collusion of the other Indians, but we can certainly ask where Padre Lamberto was during all this. The second question has a wider import. Why were the Indians raised at the mission considered the worst? We will look at that issue later. In our story up until now mission affairs have been in the foreground, and we have learned about the Guaycura in that context. But now we are fortunate to encounter a unique collection of writings in the history of Baja California that describes mission life at San Luis Gonzaga, and the Guaycura, as well, in rather meticulous detail. These are writings that have won the appreciation of anthropologists because they give us a picture of the Guaycura, but have raised the ire of others because of the unflattering portrait they paint of them. It is time to meet Jacobo Baegert. |

A Complete List of Books, DVDs and CDs