The native languages of the Baja California peninsula have often been divided into three families: the Yumans from San Javier north

, the Guaycuras from Loreto down and including the La Paz area, and the Pericú in the Cape region and the Gulf islands. But early missionary accounts differ among themselves, as do modern scholars. William Massey, the pioneering archaeologist of Baja California Sur in recent times suggests, in fact, two families: the Yuman and the Guaycuran, and he divides the latter as follows: 1Guaicurian Family

| Guaicura Guaicura Callejue

|

Huchiti (Uchití) Cora Huchiti Aripe Periúe |

Pericú Pericú Isleño

|

In this schema the testimony of P. Sigismundo Taraval played an important role. He wrote

, as we saw, about La Paz: "Comprising this mission were some 800 inhabitants who were scattered throughout seven rancherías, belonging to three main groups. One of these groups, which was related to the Indians of Mission Dolores, was that of the Callejues; another was the Huchitíes, which though reputed to be a branch of the Vaicuros yet speaks an almost wholly distinct language; the other was a small ranchería on one of the neighboring islands, belonging to the Pericúe nation. The Huchitíes group included four rancherías: the Aripes, Coras, Periúes, or Vinees, and those who are called by antonomasia the Huchitíes. These are the men that rose and, as will be related, started the rebellion."2But Massey

’s classification of the Pericú being part of the Guaycuran family rather than a separate one has been called into question.3 Don Laylander in a detailed review of the evidence, relying particularly on Padre Ignacio Nápoli’s account of the Cora, concluded that the Cora were, in fact, identical to the Pericú and linguistically distinct from the Guaycura.4Concerning our Guaycuran territory served by the missions of Los Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga, historical testimony has been more straight-forward and consistent. These people spoke Guaycura, which was the same language spoken by the Callejues in the south. But there was considerable diversity in the Guaycuran family of languages. The Monquí to the north at Liguí and Loreto appeared to have been Guaycuran speakers who spoke a tongue quite distinct from the Guaycurans in the south. We can recall how Guillén on his 1719 expedition took interpreters with him, and he clearly marked the linguistic boundaries between the Guaycura nation and the Monquí.

To the south of the Guaycura nation the Periué

, Aripe and Uchití spoke Guaycuran languages which probably differed significantly from the Guaycura to the north of them, and the Monquí. Miguel Venegas will write, for example, "The people understand one another only in some few words, which mean the same in the three languages of Loreto, Guaycura, and Uchití, and those words are very few."5 This kind of linguistic diversity suggests either that the original Guaycura had been in Baja California for a long time, or that different Guaycuran bands had originally immigrated to the peninsula.

The Uchití

One Guaycuran tongue was spoken in the mission territory of Los Dolores and San Luis

, but there were some interesting anomalies. We saw how the Guillén party on its way home from La Paz in 1721 encountered a ranchería whose people spoke Cora, and one old woman who spoke Guaycura, as well, translated. If we accept Laylander’s identification of Cora and Pericú, then we can understand their presence as an indication that Pericú territory once extended further north than La Paz, but was compressed into the south by the arrival of the Guaycuras, leaving this isolated pocket of Pericú speakers, as well as the islands in the Gulf as far north at least to San José, still part of Pericú territory. It is possible that the same kind of phenomenon might account for the fact that the Cochimí territory extended south to San Javier, while the Guaycuras still lived to the west of it, and the Monquís to the east.But there also appears to have been another non-Guaycuran speaking group in the Magdalena Bay area. Hostell in his informe of 1744 had written about Titapue near Magdalena Bay:

"The pagan Uchitíes dwell in this area. The Ikas, Añudeves, and the natives from Ticudadei have joined them. The missionary found all of them well disposed to listen to the holy Gospel, as they informed him through the interpreter of their language, which is very different from Guaycuro."6 Ernest Burrus who translated this text felt that Uchitíes was equivalent to the original Spanish text Huicipoeyes, and to Baegert’s Utschipujes.7Laylander suggests that Uchitíes is distinct from Huicipoeyes

, and that Ika and Añubeve are place names like Ticudadei, and therefore we might not be faced with a major language division, but rather, a question of dialect. Guillén, for example, in his first expedition reports an incident which took place on Magdalena Bay. Monroy and his party came upon an Indian setting fire to a stand of mangroves: "he was caught by surprise and ran to hide behind a mangrove. The interpreter spoke to him, and the Indian answered, his language not being any other, I do not understand this language. They asked him about the water hole and people, and he answered that here there are no people, I live here alone; nor is there water and I do not drink it here."8 Surprise, fear, and a somewhat different dialect rather than a distinct language could have come together to create this situation.But it is still a real possibility that we are dealing with a distinct linguistic group. Place names in the Guaycura nation appeared to be named after the bands that lived there

, or perhaps vice versa, so this kind of distinction does not rule out a group speaking a different language. Hostell in his letter to his father of 1743, as we might remember, writes: "This coming October I shall attempt to find out whether two pagan tribes, the Ikas and the Huchipoies, are ready to receive the gospel and are willing to accompany me westward to the village which would be the fourth established by me. I have many reasons to be optimistic in their regard."9 This new mission was never created, as we saw, but perhaps part of the motivation for creating it was not only the distance these natives lived from San Luis Gonzaga, but conceivably a difference in language, as well. Elsewhere Hostell writes: "My Guaycuro Indians alone make use of four different dialects. The same is also true of other missions. As a matter of fact, it not rarely happens that in one household the husband speaks one language and the wife another. Our older missionaries attribute this linguistic diversity to the fact that new groups of natives repeatedly descended from the north, bringing with them these different languages."10Baegert leaves us a general comment on the four languages of California beyond Guaycura:

"These are the Laymóna (Monquí) in the district of the mission of Loreto, the Cochimi in Mission San Xavier, and other languages toward the north, the Uchitíes and the Pericúes in the south, and the still unknown language spoken by the tribe which Father Linck visited on his trip."11 Then he reports: "My Ikas in California spoke a language different from the rest of the people in my mission."12 It is interesting to note that Baegert clearly distinguishes Guaycura from Uchití and Pericú. So both Hostell and Baegert, who knew Guaycura well, claimed that the Ikas spoke a "different," or "very different," language. This leads us to the tentative conclusion that there was an enclave of non-Guaycuran speakers in the area, or groups that belong to the Guaycuran family but spoke a very different dialect. Let’s see if we can refine this hypothesis.Could they have been Pericú speakers isolated in that area like the Coras we saw before? This does not appear likely because Hostell at the beginning of his missionary career had spent two years at San José, and thus we would imagine he knew something of the Pericú language and would have recognized it when he heard it. Taraval in describing the rebellion in the south and how the Spaniards searched for them leaves us some very interesting remarks that appear to throw light on this question. The Spaniards had been searching all over for the rebels: "Inasmuch as they had gone out and made a complete circle through the country of the Pericúes, had traveled overland from Dolores to La Paz together with the soldiers and Yaqui Indian allies, had searched along the entire coast bathed by the sea and gulf of the Californias at the time the commander went with the Dolores Indians to Loreto, there remained of all the enemy country only the far coast, that along the South Sea, which our men had not seen, traveled over, and passed through in safety. This had been accomplished, too, without harm to the faithful, and always to the damage of the unfaithful and the insurgents. Furthermore, the lands of this remote coast were the ancestral lands of the Huchitíes and, according to reports, some of their relatives still lived here. Certainly down near the shore stood a ranchería whose inmates spoke the same language as did those at Mission Dolores."13 Taraval concludes: "Then after they had inspected all this territory they planned to continue on to Mission Dolores."14 It appears that the only way to made sense out of this passage is to imagine them traveling north along the west coast toward the Magdalena Bay area. Later the soldiers, for example, made another foray from Los Dolores, itself, in which they encountered the Pecunes and Catauros halfway to La Paz who aided them in killing the shaman of the Aripes, and we are told, "since they had explored the coast along the straits, they returned by way of the South Sea and finally returned safely to Dolores."15 So according to Taraval, the Uchití once lived in the general area where Hostell encountered the Huicipoeyes speaking a very different language, and therefore it may be that Burrus was correct in thinking that the Huicipoeyes, and Baegert’s Utschipujes, were equivalent to the Uchití. This would fit with Taraval claiming that the Uchití were a branch of the Guaycurans and spoke a very different language from them. Then it is possible that the Uchitís gradually moved further south, leaving some scattered bands of Uchití speakers in the Magdalena Bay area.

The Cubí

Guillén

, himself, leaves us two terminological riddles. In the first he tells us when he traveled south of Liguí on his expedition to La Paz, "Here the territory of the Guaycura, or Cuvé, nation begins."16 It seems that this name might have been used as an equivalent for the Guaycuras as a whole. Or less likely, it might have referred to a ranchería, and while there is no Cuvé ranchería that has come down to us, there is an Acuré. The word Cuvé, itself, does not seem to appear elsewhere.The second riddle is more complicated and revealing. Members of the Guillén party to La Paz explored to the southeast

, and came upon a temporary camp whose inhabitants fled, so "they did not know if the people were Guaycuras or Cubíes."17 The implication is clear that Guaycuras are not Cubíes.In a second incident we just looked at

, on their return home from La Paz they came upon a ranchería where the people spoke Cora, "who our friends, Cubíes did not understand. However, the old woman, it appears, called to them in their language. The woman also knew the Guaycura language because she spoke well with our men."18 The old woman speaks Cora to the people in the hills who the Cubíes cannot understand, and speaks Guaycura, as well. Are there three languages involved here, or two? That is the question. We saw that Cora could be Pericú, but there might be two other languages involved here: Cubí and Guaycura. Guillén had Cubí in his party for the return trip, and may have recruited them from the southeast of La Paz to fill the places left vacant by his Indian allies who had returned north by boat. In regard to the incident southeast of La Paz, M. León-Portilla suggests that the Cubíes could be related to the Uchití who lived in that area.19In a third incident

, the day after leaving the Cora ranchería, the explorers arrived at a place they called San Higinio del Guaycuro where they found just two women and some children. And Guillén writes: "We found a ranchería of Guaycuras or Cubíes."20 It is not likely that, given the previous usage, Cubí was being used here simply as another name for Guaycuras, and so it opens up the possibility that Cubí could be living this far north of La Paz, that is, in the area of present-day San Hilario.The Cubí show up in one other document

, Guillén’s 1730 informe addressed to Joseph Echeverría where they dominate much of the text. "Your Reverence," Guillén begins, "has already well experienced how barbarous and murderous are this Cubí people (gente Cubí). They have already dared to kill those of the otra banda (i.e., the west coast) as you just saw." They fight among themselves, and the Cubí "of that part" are responsible for the deaths of the fathers of the seven mission boys. They have finished off one ranchería, as they did with San Carlos, and tried to do with others. "They are great thieves, and harmful to our people…" "For the barbarousness, then, of these Cubíes Indians is distinct from those of the north of this land, and at one accord, or half in accord, with the La Paz mission. The poverty of this mission prevents them from being called there often, and only a few visits are possible to so many and so distant rancherías." Later, in the same document, Guillén writes: "Beyond the 20 rancherías that belong to the mission and those of the mission of La Paz, this Cubí nation has as many rancherías, a few more or less, which can belong to none of these missions; for they are very distant and distinct among themselves. The 20 previously mentioned alone can pertain to the mission, and if all were reduced, would number 1,300 or 1,400 people, and the mission would have a lot of work in administering to them."

It appears that the Cubí should be taken as part of Guillén’s own mission territory, but not be identified with the Guaycuras. They seem to represent a rather distinct group of as yet unevangelized rancherías. It is likely that these Cubí were related to the Uchití found to the southeast of La Paz, and may have even spoken a Uchití dialect. Later, in a letter Guillén wrote on April 16, 1739, he tells us he had received a letter from the south about the disobedience of the Uchití and the Cora, indicating that he knows the Uchití under their usual name, and strengthening our feeling that they are in some way distinct from the Cubí.

It is worth trying to fit these remarks about the Cubí into the context of the better known history of the Uchití at this time. We read, for example, "The fierce and defiant Uchití continued to harass all those around them. Capitán Rodríguez and some eight to ten soldiers spent six months, from March to September of 1729 trying to pacify the Uchití and protect the neophytes of La Paz, Todos Santos, and Santiago."21

In 1730, Venegas tells us, Capitán Rodríguez accompanied P. Visitador Joseph Echeverría on his rounds of visiting the missions in the south, and of founding S. Joseph, and the captain "visited all the missions in the south in order to pacify their inhabitants." But it was still necessary to return in 1731 to punish "certain rancherías who had acted treacherously against their Christian neighbors."22 Venegas goes on to explain that these were the gentile inhabitants of the sierra on the contra-costa, and neighbors (confinantes) to the Christians of mission Los Dolores. Due to an ancient offense, they sought vengeance by pretending to be very friendly with their Christian neighbors (vecinos), and invited them to a feast and dance, as rancherías were accustomed to do with each other. While the Christians were dancing, their host loosed on them "a rain of arrows, darts and stones," killing 10 of them while the rest of the wounded and maltreated returned to the mission.23 The captain sent his alférez with 14 soldiers and 15 Indian warriors from Loreto and Los Dolores to punish them. But they had difficulty finding them in such rough country. But with the aid of their Indian allies they captured some of them who were brought to Loreto for punishment.24

While we could suppose, as we could do with the accounts of Taraval, that these Uchití were living along the Pacific Coast of the Cape region, the link to Los Dolores seems to imply a closer locality for some of them. Venegas clearly indicates that they were the neighbors to the Los Dolores rancherías, and this makes more sense than imagining the Los Dolores Indians taking a long trek to the Cape region in order to attend a fiesta. The story also implies that the language differences between the Guaycuras and these Uchití could not have been so great as to have precluded these kinds of festivities.

It is becoming easier and easier to imagine that the Cubí of Guillén’s informe are part of the Uchití, and while there is no need to deny the Uchití inhabited a territory between La Paz and Todos Santos, and on to the Pacific Cape region, we are faced with the intriguing possibility that related groups existed north of La Paz, perhaps both on the west coast and on the east coast. "Close relationship between the Uchiti tribes at La Paz and to the north," William Massey writes, "is indicated by marriage of Aripe women to Periúes. Periúes, Tepajiguetamas, Vinees, Cantiles: The natives of La Paz referred to the Indians living to the north as the Periúes, or as the Tepajiquetamas, Vinees, or Cantiles. The last name is derived from steep cliffs in the land of the Periúes. Inasmuch as Taraval lists the Periúes as a Huchiti rancheria, all these groups may be taken as Huchiti bands living beyond the great escarpment northwest of La Paz Bay. When Venegas (and later Clavigero) spoke of "Uchities" who were particularly troublesome in cutting land communication between La Paz and Loreto, he undoubtedly referred to these Huchiti-speaking groups."25

If the Cantiles were Uchití, or Cubí, then it would be more understandable how they could have attacked San Carlos, as Guillén tells us in his 1730 informe, which was further north on the Gulf coast, rather than having to travel up from the Cape region. In regard to the marriage of the Aripe women to the Periúe men, we can recall Hostell’s remark that sometimes husbands and wives spoke different languages, and it may refer to this variation in dialect among different Guaycura bands. The author of Descripción tells us that the Callejúes, Aripes, and Uchití all speak one language, "although it varies in some and many words by which one can be distinguished from the other, but they understand each other."26 It is in this way we can understand the incident of the Guaycuras of Los Dolores, who spoke the same language as the Callejues, going to the festival of the Uchití, and understanding them. We are also told that the Periúes speak the language of Los Dolores.27 These appear to be the same people who Rodríguez called the Pirús, or Piruchas.28

There is a final interesting postscript to this Uchití connection with the Guaycura nation. Guillén, as we saw before, when he retired to Loreto learned another language to help an old woman who could not return home. This language, we are told elsewhere,29 was Uchití. Miguel del Barco tells us that about this time the Uchití were almost completely wiped out.30 This would account for why she could not return home, and was isolated in Loreto among the Cochimí speakers and perhaps some Monquí who were now conversing in Spanish. Could it be that she was a Uchití speaker from the west coast of his original mission territory, and therefore he had a special feeling of solicitude for her? His learning of Uchití would have followed his original path of learning Monquí, then Guaycura, and finally another distinct dialect of the Guaycuran language.

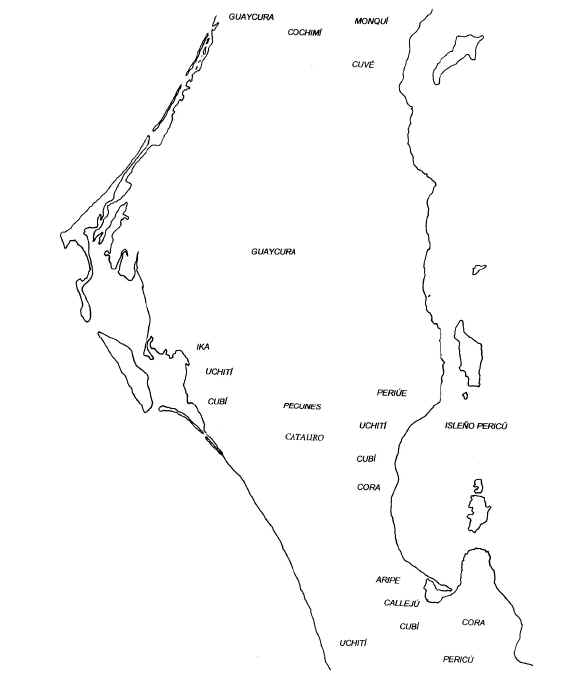

In summary, it appears we have three basic language families: the Yuman starting with the Cochimí, the Guaycura, and the Pericú. Guaycura, in turn, can be divided into the Guaycura of San Luis and Los Dolores, Monquí to the north, and Uchití to the south. The Uchití are probably related closely to Guillén’s Cubí, and perhaps to Baegert’s Ikas, as well. The Guaycura nation, then, was not linguistically uniform. It appears that there were Uchití speakers on both coasts. See Map 6.

The Guaycura Language

Most of what we know of the Guaycura language of Los Dolores and San Luis comes from Baegert’s letters to his brother, and from his book on Baja California. He was also apparently planning to write a more extensive linguistic study which Padre Visitador José de Utrera described as "a grammar and vocabulary of this language which is spoken here and in La Pasión and in Todos Santos."31 If he ever did so, it might have been left behind at the time of the expulsion, confiscated in Havana before the Jesuits set sail for Spain, or was used by Baegert for the study of Guaycura he leaves us in his book, and now lies unnoticed in some European archive. But he did, in fact, leave us the Lord’s prayer in Guaycura, as well as twelve articles of the Creed, the conjugation of the verb "to play," and various grammatical rules and reflections on the language. He also tells us: "I have also translated almost alone without help the entire Christian dogma on five sheets containing 35 paragraphs,"32 which is unfortunately lost.

Baegert leaves us a basic description of the Guaycura language. The alphabet does not have o, f, g, l, x, z, h, u, or s except for tsh. The language contains no abstract nouns like life, or death, or hope, or charity.33 But if "life" is absent, "alive" is present. It has only three or four adjectives that describe facial emotions: merry, sad, tired, and angry. Bad is expressed by adding the negation ja, or ra to good. There are words for old man and old woman, but not old and young by themselves. There are only four words for color, and the Guaycura do not distinguish yellow from red, blue from green, black from brown, or white from ash-colored. Neither do they have names for separate parts of the body. They don’t say father or mother, but rather, my father or your mother. There is a dearth of propositions, conjunctions and relative pronouns, and the conjunction "and" is placed at the end of a sentence. They lack comparatives and superlatives, and most adverbs. They have no conjunctive, imperative, and almost no optative mood for their verbs, yet Baegert gives an imperative when conjugating "to play." They have no passive or reciprocal verbs. They conjugate their verbs for the present, past or future, and sometimes have a preterit passive participle. Baegert leaves us this information with the air of someone proving that the language was extremely primitive, yet he, himself, tells us how inventive the Indians were in creating new words. Wine was evil water, and missionary, the one who has his house in the north. He even amuses us by having us imagine a missionary giving them a sermon about a European saint who did not eat meat or drink wine, and slept on the ground, a sermon, he assures us, they would find incomprehensible because they don’t drink wine, rarely get any meat to eat, and habitually sleep on the ground.

Map 6. Tribes and Languages

A Guaycura Vocabulary

If we add to Baegert’s work Clemente Guillén’s trip journals and reports, and a few odd words from elsewhere, we can come up with a Guaycuran word list. In this connection, a valuable aid for Guaycura words and the words that still exist in Cochimí and Pericú is Gilberto Ibarra Rivera’s Vocablos indígenas de Baja California. L= Baegert’s Letters. O=his Observations. V=Vocablos. Most words when not otherwise noted come from the language section of Baegert’s Observations, and most of the unsourced place names come from Guillén.

aata cera - evil water, or wine (L 144)

Aburdebe - place name (Hostell 1744)

Acuí - place name

Acuré - place name

Acheme - place name

Achére - place name

Adagué - place name

aëna - above, sky

Aenatá - place name

agenari - a dance (O 89)

aguax - corn for the inhabitants of La Paz (V 51)

Aguí - place name

aipekériri - who knows that? (O 92)

aipúreve - From thence

Airapí - place name for La Paz

akátuiké - acknowledge

Akiá - place name (1730)

amaeka - dance floor (L 202)

ambéra didi - their favorite Guaycuran song

ambía - pitahaya, but also by extension a year

ambúja - a week, and house, which equals church

amukíri - to play

ánaï - woman

Aniritihué - place name

Anjukwáre - Guaycura band, Baegert

Anyaichirí - place name

Añudevés - Guaycura band

apá - root for forehead

apánne - great

Apaté - place name

Aquiri - place name

áre - root for father

Aripaquí - place name

Aripes - Guaycura band

Aripité - place name

Arecú - place name

Arudovichi - place name

Arúi = Hiray? place name (V 55)

Asembavichi - place name

atacámma - good

atacámmara - evil

atacára - evil

atemba - earth

atembatie - to be sick, or to lie, to be on the ground (O 77)

Atiá - place name (1730)

Atiguíri - place name

atukiára - evil

atúme - have

be - I, to me, me or my

bécue, écue, tícue, kepécue (i.e., my, thy, his, our mother) when speaking of women (O 97-8)

becún, or beticún - my

bedáre, edáre, tiáre, kepedáre, etc. (i.e., my, thy, his, our father) when speaking of men (O 97)

betanía, etanía, tishanía (my, thy, his word) (O 98)

Bonú - Monquí place name

buará (vara) - nothing

búe - food

búnju - below

Caembehué - place name

Cahué - place name

Callejúes - Guaycura band

Candapán - place name

Cantiles - Spanish name for a Guaycura band

Catauros - Guaycura band

caté - we, us

cávape - they

Chiyá - place name

ci perthe risi - who knows? (L 178)

Cochimí - people who live in the north (V 64)

Cocloraki - place name, Hostell Informe of 1744

Codaraqui - place name

Cogué - place name (1730)

Conchó - place name for Loreto in Monquí meaning red mangrove (V 166)

Cubíes (Cubí) - Guaycura band

cue - root for mother

Cuedené - place name

cuncari - much (L 146)

Cunupaqui - place name

Cutoihuí - place name

Cuvé - another name for the Guaycura

cuvumerá - will wish

Chiyá - place name

Chirigaqui - place name

Chuenqui (Monquí) - place name

daï - thou art

dare - father

datembá - earth

dei - ever

Devá - place name

déve - on account of (O 98)

Deverá -place name (1730)

dicuinocho - shaman

didí-re - well

dipuá - indigenous tree in Monquí which the Spanish used for forage (V 74)

écun or eiticún - thy

Edú - Indians of the Loreto area

eï - thou, to thee, thee, thy

Eguí - proper name (Ibarra 143)

Emma - devil (L 145)

éneme - future tense ending to verbs

enjéme - then

entuditamma - bad or ugly women

entuditú - ugly, or bad

epí - there is

ete - man (V 75)

Figuaná - place name

Fiquenendegá - place name

Guachaguí - place name (1730)

Guamongo - spirit who lives in the north and sends diseases (Monquí)

Guaxoro - a Pericú name for the Guaycuras of La Paz meaning friend (Venegas, V 79)

Guerequaná - place name

Gujiaqui - spirit sent by Guamongo

híbitsherikíri - has suffered

Hiray - place name (See Arúi)

Hucipoeyes - band of Guaycuras

íbe - alone

Ichudairí - place name

ié - to be ashamed (O 83)

ïebitshéne - commanding

Ikas - band of Guaycuras

Iriguái - place name (1730)

irimánjure - I believe

ja - a negation added to words (O 96)

jake - to chat

jatacrie - deer catcher, a large eagle that can catch deer (L 200)

jatúpe - this

jaûpe - here

jebarrakéme - obey

Joeminini Generis - a mythological bird (L 201)

k or ku - plural suffix to verbs

kanaï - women

kakunjá - protect

kéa - are - under earth

kejenjúta

kên - give

kenyei - mescal

kepe - our, us

kepecún - our

kepe dare - Our Father (L 145)

kepetujaké - us do

keritshéü - gone down

kicún - their

Kodaraguí (Codaraguí) - place name

ku - will

kuáke - talkers

kuitsharraké - forgive

kumbáte - to hate

kumutú - thinkers

kunjukaráü - washed

kupiabake - fighters

kutéve - didí-re - confess well

kutikürre - stretched out

kutipaû - beaten ones

Laymón, Laimón - applied to both the Monquí and the Cochimí (V 88)

Liguí - Monquí place name

mapá, etapá, tapá (i.e., my, your, his forehead) (O 98)

matanamu - a light red snake with black spots (L 180)

me - out, in, with, etc. (O 98)

me - will

me - his

me or meje - future tense ending to verbs

me akúnju - three

méje - come, will be

menembeû, enembeû, tenembeû (my, thy, his pain) (O 98)

Michiricuchayére - place name

Michiricucurébe - place name (1730)

Mitschirikutamái - Guaycura band, Baegert

Mitschirijutaruanajére - Guaycura band, Baegert

Mitschirikuteuru - Guaycura band, Baegert

minamú, einamú, timamú (for my, thy, his nose) (O 98)

Monquí - natives of Loreto

namú - root for nose

Nautré - place name

nembeú - pain

neunqui - a fruit (frutilla) found in the mountains (Monquí)

nimbé - a dance of the Monquí

Niunquí - place name. (V 95, Laylander 80) May be Cochimí word.

nombó - a bush

notú - heaven, or above, or on high

Onduchah - place name

Pacudaraquihué - place name

páe - as

pánne - great

pari - much (L 146)

Paurus - Guaycura group

payro - thanks (See below.)

pe - out, in, with, etc. (O 98)

Pecunes - Guayacura band

pedára - born

peneká - sits

pera kari - parent (L 145)

Perihúes (Periúe) - Guaycura group

peté - you, plural

piabaké - to fight

pibikíri - has dried

Pirus (Piricuchas) - Guaycura band (V 99)

pu - all

púa - embarcaciones

puduéne - can

pui - mescal (O 179)

punjére - made

Quaquihué - place name

Quatiquié - place name

Quepoh - place name

Querequana - place name

Quiaira - place name

ra - a negation added to words (O 96)

râupe - past tense endings to verbs

râúpere - past tense endings to verbs

re or reke - present tense ending to verbs

Remeraquí - place name

rí - oh!, optative ending

rikíri - is buried, was, past tense endings to verbs

rujére - past tense endings to verbs

Tacanapare - place name

tanía - root for word

taniti - shaman (L 203)

tantipara - shaman (L 203)

Tañuetiá - place name meaning place of the ducks

tau - this

taupe - this

tayé - wild mountain sheep (V 104)

te - out, in, with, of, etc. (O 98)

Teachwá - Guaycura band, Baegert

Tecacua - place name (Guillén letter of 1739)

Tecadahué - place name

Teenguábebe - Guaycura band, Baegert

têi - you

tekerekádatembá - arched earth

témme - being

tenembeú - his pain

tenkíe - reward

Tepahui - place name

Tepajiquetamas - Guaycura band

ti - people, men

tiá-pa-tú - one who has his house in the north, or missionary

tíare - Father

Tibieres - tribal name on Kino map

tibikíu - be dead

Ticudadeí - Guaycura band

Tiguana - place name

tikakambá - help

tikére undiri - to touch each other’s arms or hands, or to marry (O 73)

tiná - on or upon (O 98)

Tipateigua - place name

tipé - tshetshutipé - alive again

tipítsheú - on account of (O 98)

Tiquenendaga - place name

Titapué - place name

titshánu - his son

titschénu tschá - child of a wise mother, or horse and mule

titshuketá - right hand

Tiyeicha - ceremonial wand meaning, "He can talk." (Hostell, Burscheid letter 1758)

Trepu - place name

trienquies - shamans

tshakárrake - praise

tshetshutipé - again

tschie - and

tshukíti - gone to

tschumuge - to kiss (L 145)

tshípake - to beat

tshipitshürre - a beaten one

tucáva - the same, they

tutau - he

Uchití - Guaycuran related band

Udaré - place name

uë - anything

Uhauh - Monquí place name (V 109)

Uhonzi - Monquí place name (V 109)

umutú - to remember, think

untâri - day

Unubbé - May be Cochimí word. (Laylander 80, V 110)

uretí - make

Uriguai - (Taraval 159)

utere - sit down? (See below.)

uteürí - give

Utschipuje - Guaycura band, Baegert

vára - nothing (O 88)

vérepe - same

Vinees - Guaycura band

Waicura, ro, Waicuri, Waikuri

Among indigenous personal names we find Alonzo Tepahui and Juan and Nicolás Eguí which may be Guaycuran or Monquí. Various word elements appear over and over in the list of place names.34 Tañuetiá is the place of the ducks, so conceivably some of these endings mean "the place of." Aena means above, and by extension, heaven. Aenatá is the native name for present-day Jesús María and could conceivably mean "the place above," that is, the place in the far northern part of the Guaycuran territory. Even the name Guaycura, according to Venegas, is not their own, but the name the Pericú gave them meaning friends.35 Edú is, according to Barco, the name given to the Monquí by the Cochimí, and it means people of another tongue, but Venegas tells us it is the name given by the Monquí to those further south. During Francisco Ortega’s voyage of 1632 the Spaniards coming from the mainland hit the Gulf coast eight days coasting above the Cape. There Diego de la Nava reports on an incident in which he held out his hands in peace, and the natives said, "Utere, utere," which he took to mean, "sit down," or something similar." And in return for the gifts he was carrying, they said, "payro," putting their hands on their breasts and inclining their heads, so he took that to mean thanks. This far north we could very well be dealing with the Guaycura rather than the Pericú. If that is true, then payro would be thanks, and perhaps utere is sit down, but it finds an interesting parallel with uteurí, meaning give, i.e., perhaps in the sense of give us the gifts you are carrying.

The Origin of the Guaycura Language

In 1966, Karl-Heinz Gursky suggested that Guaycura was a member of the Hokan language family. He gave a number of parallels to other Hokan-Coahuiltecan languages to support this assertion. Among the most obvious: alive in Guaycuran is tipé, while in Yuma it is ipay (to be alive), and in Coahuilteco it is tepyam. Alone, which is ibe in Guaycura, is ipa in proto-Hokan. Arched earth, which is tekerekádatembá in Guaycura, is tekerakwa (háka tekerákwa) for arched, or curved lake in Yavapay. Ambúja, meaning house, or week, in Guaycura is amma in Shasta, and ama in proto-Hokan. Piabake, which means fight in Guaycura, is payiwak (beat) in Comecrudo. And house in Guaycura, ápa, is awa in Chimariko, Diegueño, and in proto-Hokan, and ava in Mohave, as well as Yuma.36

"Additional comparisons of Gursky’s list," writes Laylander, "with more recently published data on the Yuman languages and on proto-Yuman and Cochimí do not add materially to the similarities already found by Gursky. It seems fair to conclude that the available evidence is sufficient to show that no relationship between Guaycura and either the Cochimí or the Yuman family exists which is as close as the relationship between the two latter groups."37

In 1967 Morris Swadesh, apparently independently, reached conclusions similar to Gursky by comparing Guaycura with the Coahuiltecan languages. Among the more obvious comparisons he made: I, which is be in Guaycura, is ne in Nahua; tey (you) in Guaycura is te in Nahua; the negative ending ra in Guaycura is sa in Cotoname, and apanne (big) in Guaycura is penne in Jicaque. Swadesh felt that Guaycura had separated from the other Coahuiltecan languages somewhere around 5,000 years ago.38