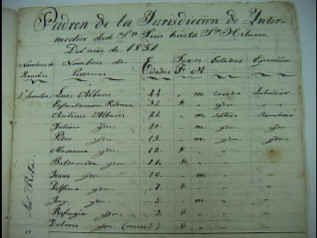

1851 Census of Intermedios

On the Trail with Arthur North

Rancho Jesús María 1906

Intermedios cowboys 1906

Making Mescal

Benigno de la Toba and family

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

1851. Intermedios has grown , and we are fortunate to have a census of its southern section which is worth reproducing in its entirety.Baja census Agosto 24 18511 Padron de la Jurisdiccion de Intermedios desde Sn Luis hasta Sn Hilario. Del año de 1851

Ranchos 18) familias 35) hombres 134) mugeres 127) total almas con los cuatro ultimos 265 Intermedios Agosto 24 de 1851. A leal de intermedio Luis Alvarez

Map 8. Intermedios Ranchos by the 1850s Map 8 shows many of the ranches for which we have evidence that they existed by the 1850s. They spread organically most likely from the first ranchos of the area by the departure of their sons whom the home ranch could not support. These sons would go up or down the arroyo, or find an unexploited spring, and with the help of their families, start a new rancho. In this way the sierra and plains of Intermedios gradually became covered by a network of ranchos bound together by family ties. This process, at least for the Sierra de Guadalupe in the north, peaked around 1900 when the most remote water sources had been utilized.2 It may well have been the same for Intermedios. Part of this extensive utilization of the land was the creation of changing, or moving, ranchos which in times of adequate rain were established in places without adequate permanent water, and in times of drought, retreated to wait for the next rains, a practice that still continues. The rancheros of Llanos de Kakíwi (Quaquihué), for example, returned to their ranch after a long absence after the rains of 2001. 1852. Feb. 7. Tomás Lucero receives title to San Evaristo. (L236) Oct. 11. The local authorities are laying out a plaza and a courthouse west of the church in San Luis. They are also creating a register of sites. (PMA, V48bis, 470) Dec. 15. Francisco Betanceur (Betancourt) reports to the authorities that Canuto Murillo is building a corral in a place called Veredas without a legal title. (PMA, 12, V48bis, 549)3 A map of lots for San Luis Gonzaga "of the new population of San Luis Gonzaga promoted this year of 1849."4 1853. Lassépas mentions a census of this year.5 Oct. 12. Luis Romero at Santa Cruz. (L237) The descendants of Felipe Romero sell San Luis to Pablo de la Toba. (G28) 1854. Jan. 2. Pablo Álbarez writes to the authorities that three days before he had gotten word that there were something like seven whaling ships in Magdalena Bay, and he has sent someone to gather further information. He signs this communication: Dios y Libertad, Intermedio. (PMA, I, V 52, 005) April 8. Los Dolores, Pablo de la Toba at the auxiliary barracks of Intermedios. (PMA, 694, II, V53, Bis L4, 1ff.) May 15. La Pasión. Benigno de la Toba takes an oath as the justice of peace of Intermedios. (PMA, V54, II, V54, L5, 1ff.) Pablo Álvarez, Judge of Intermedios (PMA, V53, 003.) The diocese of Lower California is separated from that of Monterey. A Vicar General is sent who arrives on June 13, 1854. He is Juan Francisco Escalante, accompanied by Mariano Carlón, a curate from Buena Vista in Sonora, and Anastasio López who came a few days later, a curate from Guevavi in Sonora, and Trinidad Cortéz. "On December 7th all reached the extinct Mission of San Luis Gonzaga, fifty leagues from Loreto. The Vicar was very active here as elsewhere. Eighty-one persons were confirmed. The feast of Purísima Concepción was celebrated with much splendor; and on the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe there was a levitical High Mass, Solemn Vespers and a procession. All this caused much admiration, because such a splendid ceremony had never been witnessed here. Similar festivities were prepared for the people elsewhere." "On December 18th," the Vicar writes, "we left San Luis Gonzaga, and, after journeying fifty leagues, we reached the port of La Paz on December 23rd."6

The 1853 Tax Roll July 17. Benigno de la Toba at La Pasión as the Justice of the Peace of Intermedios submits a tax report of the individuals who possess land in Intermedios that covers part of the area for the year 1853.7 Lista nominal de los individuos que poseen Citios en esta comprencion de Yntermedios y exectuaron sus correspondientes pagos hasta el año de 1853 en cumplimiento del Bando de 8 de Junio del precedente año mandado por el gobierno politico de este territorio.

Citios y estan anotados en el libro de registros de ellos en este Juzgado y no reciden en esta comprencion. medio citio de Navidad - D. Leonardo angulo en el Nobillo recide La Salada. los Stras Ruffo. en La Paz Tarabillas. Srs. Flores. en el Tule. No esta anotado en el libro correspondiente y recide en esta comprencion San Hilario de Sr. Juan Gomes de Aguiar Estos ultimos no han ni pagado su correspondiente en esta jurisdicion ni mostrado papel de satisfaccion alguna en jurigado Estendida en la Pasion en Intermedios a 17 de Julio de 1854. (firmado) Benigno de la Tova A la Jefetura politica de Baja California del Juzgado de Paz de Intermedios He also mentions other places that appear in the registry book of San Luis, but whose owners do not reside in the area: a half site of Navidad, D. Leonardo Angulo who resides in El Nobillo; La Salada belonging to Stras. Ruffo in La Paz; Tarabillas belonging to Srs. Flores in El Tule. Also not noted into the book and residing in this area San Hilario of Juan Gomez de Aguiar. These last have not paid. Once in the sierra near La Pasión I talked with a rancher who made a visible effort to recall an Indian place name in the area. That name was Tecadahué, which I had never heard, and which I later encountered in this document. Oct. 23. Petronilo Romero, the military commander of Isla de Carmen writes to the authorities for help because he was leaving the point called San Evaristo when his boat was assaulted by a strong storm at three in the afternoon, and foundered on the beach at Los Dolores. It is now ten in the morning. Signed, Dios y Libertad, Playa de Los Dolores. (PMA1711) Nov. 4. Julián Álvarez marries Elvira Orozco. He is a native of Intermedios, (which probably meant San Luis Gonzaga, itself) living at Rancho del Coyote, and the son of Luis Álvarez and Expectación Redona. Dec. 16. Cayetano Romero marries María Guadalupe Espinosa at ex-misión San Luis. He is the son of Encarnación Romero and Mercedes Baeza, and she is the daughter of Cornelio Espinosa and María Guadalupe Gerardo. Padre Mariano Carlón officiates. (G478) Dec. 17. Salvador Osuna and María Ramona Valenzuela are married by Padre Carlón at San Luis. 1855. Jan. 21. Antonio Santiestevan, Bahía de la Magdalena, title to three sites. (L238) June 10. Salvador Villarino, Ramón Navarro, Francisco Graña, title to six sites Hiray. (L239) June 14. Padre Carlón is left in La Paz, Bishop Escalante and Padre López start visiting again. for from La Paz to the border there is no priest at all. They arrive at San Luis and celebrate the feast of St. Aloysius. On July 5 they set out for San Ignacio. July 2. Magdalena Bay, Dolores Lucero petitions for the site Agua Colorado which is given to him on Oct. 9, 1855. (PMA, II, V59, L7, 2FF, 1075) Pablo de la Toba registers Iritú and El Plátano on Feb. 12, 1857, paying a fee of 50 pesos each. El Plátano, title, Dec. 3, 1855. (L238) Dec. 16. Estanislao de la Toba writes about the election in Intermedios. (PMA, II, V61, L12, 1FF, 2117) 1856. Sept. 15. Félix Gilbert receives title to Llanos de Hiray. (L81) Dec. 25. Luis Álvarez, title to El Mechudo, 20 pesos. (L215) Dec. 28. Hermenegildo Lucero, title to Pozo del Colorado. (L215) 1857. Feb. 5. Some time after this date Padre Anastasio López is visiting the settlements to the north. Nov. 26. Bishop Escalante visits the north. Dec. 13. Antonio Arce receives title to La Fortuna. (L270) Ulises Urbano Lassépas leaves us the following information: Intermedios sur, population 157 in 1857, Intermedios norte, population 163. filling in from a notice of 1853. The 1851 census figure which covers most of Intermedios sur, is 265 in contrast to Lassépas’ 157 in 1857. If we use this higher figure with the one he gives for Intermedios north, we arrive at 422 people for the area, which stands in contrast to the much greater Indian population which even at the time of their exile after a severe decline totaled 760. Lassépas also leaves us a description of Los Dolores in 1857: "Entirely destroyed: abundant spring at a distance of 16 kilometers from the Gulf on an east-west line with the northern point of the Isla de San José. Rancho and orchard. Population 450 converted Indians in 1768. Population in 1857, 6 inhabitants." (L186) This appears to refer to La Pasión, but if it does it is misleading, for as we can see from the 1851 census, there are many more people in the area. The six inhabitants would then refer to the people right at La Pasión. Titles without dates given by Lassépas, and therefore in effect by 1857 or before: J de Vargas La Relumbrosa; Pablo de la Toba, Los Dolores; Juan Gómez, bought San Hilario; A native of Portugal, married in California with a family, a whaler, lived here for 25 years; blind. (L281) Francisco Sosa y Silva; A native of Portugal, a sailor, married with family, lived in California 22 years, bought El Cajón de los Reyes, and other urban places and an orchard in La Paz. Held various municipal offices. (L281; CB69) Francisco Betancourt, Santa Cruz, Palo Verde, La Soledad, Arroyo de Sauce, San Juan. (L256-257) A native of Portugal, a whaler, married with family, 25 years in California, was alcalde of Intermedios. (L281) Lassépas gives the population of the Municipio of La Paz as 1,379, and that of Comondú as 1,322. 1858. June 10. San Luis has a new bell.8 1859. June 26. Jesús Morillo marries Isabel Amador at San Luis. Padre Anastasio López presides. He is the son of Justo Morillo, and Valentina Álvarez, and she is the daughter of Clemente Amador and Ventura Roma. Andrés Higuera marries María Santos Sandoval at San Luis. (G480) Summer. Bishop Escalante visits as far as Loreto. 1861. Valdomé Álvarez dies in a smallpox epidemic at age 15 at Rancho San Luis. (G565) 1863. J.L. Hopkins of San Francisco starts a newspaper in La Paz called El Mexicana. "Perhaps the consequent dissemination of news," Arthur North tells us, "was responsible for the fact that in the same year speculators gathered a great number of altar ornaments and paintings from the missions and placed them on exhibition in San Francisco. Some of the paintings were said to have been the work of Murillo, Cabrera and Velasquez; few of them returned to the missions."9 1864. Benito Juarez for 100,000 pesos in gold grants an enormous concession in Baja California from 31 degrees north to 24 degrees 20 minutes to Jacob Leese which includes mineral and whaling rights, and a scheme for colonization. Leese transfers his rights to the Lower California Company which in Dec. 1866 sends a scientific commission to evaluate the area led by J. Ross Browne, and which includes William Gabb. The commission renders a negative judgment about the prospects for colonization. In 1870 California newspapers are offering free land to colonists in the Magdalena Bay area claiming pure black humus soil and grass higher than the shoulder of a horse. (G393) The Lower California Company takes the colonists and uses them for harvesting orchilla, a lichen used to make dye. In April, 1871, a census by the Mexican government finds 21 North American families, 54 Mexican males, and 426 orchilla workers. Since one of the provisions of the concession was the colonization of the area by 200 families, the concession is revoked and then converted into one to exploit orchilla from 1872 to 1878. Orcilla collection was carried on "by Joseph P. Hale (1878-1880) and J. Conrado Flores and James Hale (1881-1893). The latter, in 1883, formed Flores, Hale y Compañía, added colonization to their enterprise, and in 1889 established harbor facilities at Puerto Cortés on Isla Margarita. The introduction of aniline dyes in the 1890s brought a decline in the orchilla market..."10 1867. Road notations: From La Paz to Dolores del Sur, 90 miles. From Dolores del Sur to San Luis Gonzaga, 45 miles. From Dolores to Loreto, 90 miles by the long gulf road.11

William Gabb, American Naturalist The surveying party, led by J. Ross Browne, which landed at Cabo San Lucas on Jan. 5, 1867, stands in contrast in almost every way to that of W.C.S. Smith. We have the report of the naturalist William M. Gabb of the journey through our chosen area. On Jan. 23rd they crossed the arroyo de Guadalupe and reach the ranch of Agua Colorado, and camp a mile from the ranch house. The rancheros come to visit and were already informed that the party was on its way. "Throughout the whole journey we never found a spot so retired but that, when we reached it, we found that our coming was expected, and our business known."12 They have an unexpected encounter at the ranch house as they passed it the next day. "At the house, we were surprised at being addressed with a civil "Good-morning, gentlemen," in excellent English, by a bare-footed, very ragged individual, whose countenance, unnecessarily black, with flat nose and thick lips, showed at a glance that he was not of Mexican or of Indian origin; his curly but not woolly hair seemed to imply that he was not an African, nor did he look like a Kanaka. He soon told us his story. He was a runaway sailor, spoke but little Spanish, had reached here on his way to Comondú, where he claimed to have a friend. The Mexicans urged him not to undertake the trip, because, alone and on foot as he was, and ignorant of the many trails that cross the plains of the Magdalena in all directions, the chances were almost certain that he would perish from thirst. Even Mexicans, born in the country, but unacquainted with these plains, do not dare to venture it without a guide; and many a thrilling story is told, by the flickering light of the camp-fires, of men bewildered in this sea of cactus, who, after almost incredible sufferings, have only escaped with their lives to tell their tales of horror. Many a poor wretch has left his bones, picked clean by the coyotes, to tell that he, unable to find his way out, had died from that most terrible of tortures - thirst. Our dusky friend, however, did not appear to dread such a difficulty, and replied, with a little tone of pride in his voice, that he was an Australian bushman, and had been used to such things all his life. He did not think the risk would be very great for him, and thought "he could get along." Sure enough, that same evening, almost before we had become fairly settled in our camp, twenty-four miles off, he came along, his whole baggage consisting of a quart bottle. He stayed an hour or so, got something to eat, refilled his bottle with water, and started off again. The last we saw of him was at La Salada, near Magdalena Bay, where he had contracted to work for a neighboring ranchero for a while, and where, as he informed us, he had already established "relations" with one of the old man’s daughters."13 They traveled 24 miles and camped, and by noon the next day were at the water hole of La Palma, "probably so named because there is not a single palm in sight."14 From there they went on to La Salada, six miles from Magdalena Bay, the last part of which was down an arroyo and stopped there. Further up the arroyo there were ranches every mile or two. They proceed to the bay and contact the whalers there and explore the surroundings. Then the party splits up and Gabb’s section proceeds overland 18 miles to rancho Buena Vista. The next day, the 29th of January, they stop at a little rancho to get water. On the 30th, after going a further 17 miles, they reach San Luis Gonzaga and Gabb makes a sketch of the mission building, and describes the church as being "in excellent preservation."15 They camp at El Ranchito, an abandoned ranch. Then they go on 23 miles to Los Cerritos, and then a further 15 to Jesús María. On the 2nd of Feb. they travel 18 miles up the arroyo of Santa Cruz. They camp over the next day, which is a Sunday, and have another strange encounter. "Some time after dark, on Saturday evening, a man with a peculiar-looking hump on one shoulder, rode into our camp, and, in an odd kind of voice, asked us a variety of questions as to who we were, where we were going, and what we were doing. He declined our invitation to dismount, saying he had come from a rancho in the mountains off to one side of our trail, and was going to Loreto to get some medicine for a sick man. After questioning us to his entire satisfaction, and convincing himself that we were what we represented ourselves to be, he suddenly straightened himself up in his saddle, the hump disappeared from his back, he pushed his hat back from his face, and his voice assuming a natural tone, he laughingly told us all he had said before was a lie. He was a servant at the adjoining rancho of Santa Cruz, and he had come down to find out who we were."16 They had heard that the subprefect of Mulegé, Señor Larraque, was impressing soldiers to send to the other side, and so everybody was on the lookout. On Feb. 4th they climb up the arroyo, and the next day travel down to the gulf coast. 1869. Loreto Orantes and José Valdés, living in Intermedios. (CB63, 71) 1874. John F. Janes, who wrote of his adventures in Baja California in 1874-1875, under the pen name of Stickeen, tells us he sailed to the Isla de San José in December, 1874 and talked with pearl divers there. He saw a pearl worth $400. He also saw an Indian fish trap made of stones which he attributed to the time when the Jesuits had a mission there. On his way to the Isla de Carmen a wind forced them to put in at Los Dolores where they "were entertained by a nephew of Mr. Van Borrell of La Paz. It being about fruit season, we had lots of watermelons, figs, dates, pomegranates and what the natives call Sang Dieu, not forgetting the national fruit Pilatici, which grow wild all over the territory. I stayed one night and a day; but getting short of rations, made for La Paz."17 He left Cabo San Lucas on February 27, 1875, and the next morning stopped at Magdalena Bay where there was fine village of 20 houses and they took on 800 bales of orchilla.18 1880. Francisco Vargas visits the parishes of Baja California for the Archbishop of Guadalajara and writes to him that the central part of the peninsula is called Intermediates and has a radius of 20 leagues, and there has been a drought going on in Baja California for 5 years.19 1895. Dec. 20. Father Pettinelli and a small band of Italian priests come to administer to the spiritual needs of Baja California. 1896. May 7. Jacinto Amador is born to Juan Amador and María Cota, both natives of La Soledad. His paternal grandparents are Jacinto Amador and Pilar Ojeda, and his maternal grandparents Tomás Cota and Pilar Cota. 1900. Inés Romero born on April 20, the daughter of Florentino Romero who was born in Los Ochemes (Achemes) and lives in Angel de la Guardia. Her mother was born in San Pedro, her paternal grandparents were Felipe Romero and María Amador, and her maternal grandparents, Jorge Higuera and Gertrudis Talamantes. (G562) 1902. "…in 1902 and 1908 the Chartered Company of Lower California and Magdalena Bay Company, respectively, attempted the establishment of cattle raising in the area. From 1912 to 1915 Aurelio Sandoval operated a fish cannery on Isla Margarita; however this also failed, as did the development companies which were beset with problems of financing and stockholder disputes. "During this occupation of Bahía Magdalena by foreign entrepreneurs, the U.S.S. Narragansett under George Dewey surveyed the bay, and after 1883 it became an informal supply station for U.S. naval vessels. From 1897 to 1907 Mexico permitted use of the bay by the United States Navy as a gunnery range; however, in the latter year a formal lease for a U.S. coaling station was denied. United States scientific expeditions also visited Magdalena during the same period, and in 1889 W.E. Bryant, Charles D. Hains, and T.S. Brandegee explored for the California Academy of Science while in 1905-1906 Edward W. Nelson and E.A. Goldman conducted a similar reconnaissance."20 Edward Nelson stopped at the cattle ranch headquarters of the chartered company of Lower California at Matancita, managed by W.J. Heney, and the proceeded to take a trip with Heney by boat to Magdalena Bay. Sea turtles were being shipped from the bay to San Francisco monthly. When Nelson continued his journey, he went from Matancita to Servatillo, La Cruz on the Llanos de Hiray, El Sauz, Agua Colorado to San Hilario, and then on to La Paz.21 Arthur North, American Writer 1906. Arthur North in Campo and Camino in Lower California recounts his travels south through our chosen region in a great hurry because he had just heard of the San Francisco earthquake and wanted to reach La Paz to get information about how his family there had fared. In San Javier he is told that the shortest route to La Paz is 100 leagues by way of the San Luis camino. In his mind, that 100 would be closer to 65. The other route with the thought he might find a steamer in Magdalena Bay would be to travel to La Paz via Mantancital (La Matancita) near the bay which would increase the distance by 50 leagues. His guide had traveled through the country before by the Golfo Camino, and he had an ancient map that was fairly accurate. (It was probably the map of M. Duflot de Monfras in his 1844, Exploration du Territoire l’Oregon, des Californies et de la Mer Vermeille that North had characterized as "most excellent."22 He describes the ancient caminos of the padres as clogged with stones. One road was called Tepetates Road.23 One morning he meets a gaunt Italian walking at full speed on his way north with no more equipment than his long dagger and a canteen. Later, he runs into a captain of the rurales who is searching for an offender. He describes the typical ranchos he encountered along the way. The houses were mere huts, he tells us, with thatched roofs and stake and mud walls. The food was cheese, dried beef, milk, beans, tortillas, wild honey, coffee and salt. At San Luis Gonzaga, the home of Benigno de la Toba, they see "an extensive red brick store, the most imposing modern building in Lower California."24 Two days later they meet Don Benigno on the road, and North describes him as about 45 years old with the manners of a gentlemen used to the company of gentlemen. De la Toba has 100,000 acres with 20 wells and 20 families. The wells operate by a boy or girl on a mule pulling the bucket up on a rope connected to a wheel. The bucket is then emptied by a man into a trough. From San Luis they take the Salto de los Reyes camino, and deep in the arroyo they find the Salto Los Reyes about which place he reports the legend of the king of the Guaycuras who leapt off this cliff, followed by the king of the Pericú. North also tell us about a Padre Marsellano, a young Italian priest whose territory stretches from Mulege to San Luis, and ten Italian secular priests in Baja California.25 1919. The Italian priests withdraw under the provision of the constitution of 1917 which prevents foreign priests from officiating. 1920s. Only two or three automobiles had reached La Paz, and most people returned by boat. In the 30s the frequency had gone up to one a month, and in the 40s, one or two a week.26

Griffing Bancroft, American Sailor 1932. Griffing Bancroft anchors his boat, The Least Petrel, off of rancho Los Dolores. "The most interesting incident of our short stay was the arrival of a burro train from the highlands of the interior. There were brought on the backs of the pack animals hides and cheese, tanbark and firewood, all destined for the little ship that was expected within the next few days. The drovers were of the peon class, in shirt and overalls, barefooted and wearing wide-brimmed hats of straw. A small keg of water, a coffee-pot, tin cups and one blanket apiece constituted their full equipment. They traded rather than sold, coffee and sugar being the chief needs, flour, beans, and bolts of cloth coming under the heading of luxuries. It is only when one appreciates with how little they are content with that he understands how they can survive along the borders of this furnace… "We saw in Dolores Bay another class of men who, for want of a better name, might be termed vacqueros. Small groups, usually mounted on mules, freely rode in and out of the hacienda. The bodies of their wiry little animals were almost covered by great stock saddles that represented the financial ability of the owner to make a display. There was an excess of heavy, deeply carved leather, on the stirrups were long tapaderos, and from the horns hung decorative saddle-bags. The other ornaments, indicative of the rider’s taste and purse, included everything a Mexican saddle could have. There were used both ropes of horse-hair and lariats of rawhide, neatly coiled and tied. Often a thirty-thirty rifle was attached, revolvers being rare and shotguns unused. Bridles were conspicuous with massive Spanish bits, with martingales and heavily hand-carved silver trimmings. "The clothing worn was representative of Lower California and unlike anything to be found along the United States border. The leather jackets, always short, varied in color and material according to the taste of the owner. They might be of deer hide or of cow leather tanned to a burnt orange. The chaparajos were drawn in at the waist but flared at the feet until they covered the sides of the animals. Fringes of the brightest colors, of orange or red or blue, were nationalistic, if indeed, not purely local. Sombreros were heavy and elaborate and massive spurs with absurdly large rowels were worn upon shoes, never on boots. "These riders are the most picturesque characters we had seen. Their mounts were so tiny that by the time the long leather dust coat had been thrown over the rider’s shoulders little remained visible of the animal. When the mount selected was a donkey the effect was laughable. A finishing and appropriate touch came with the decorative knife, conspicuous and ostentatious because of its large bone handle and its heavy silvery inlay. The men themselves were no less interesting than their costumes. Their primitive courtesies and their interest in us - the Partner was the first American woman most of them had ever seen - won us from the start. We left the kindly people with more than a tinge of regret. The hacienda had shown us the best and by far the most appealing side of the Mountains of the Giantess."27 1940s. In the early 1940s Ulises Irigoyen, with his companions, drove north from La Paz. The first part of the road which headed towards Magdalena Bay had been started by Agustín Arriola in 1921. It went by way of Conejo to the arroyo of Venancio, 129 kilometers from La Paz. Then by Laguna Verde to Médano to arrive at the Llanos de Hiray where Irigoyen notes that there surely must be water not far below the surface, and therefore irrigated farmland is possible. Travelers through the region much earlier had also noted this possibility. Then they arrive at Rancho Refugio where Señora Dolores de la Toba de Camacho has lived since 1927. The road splits, and the branch to the left goes toward the bay at a place called Médano Amarillo, and then on to Buena Vista. Before Médano and the grade to Buena Vista the road branches and goes to El Pilar. 1950s. Los Dolores, small ranching community, population 31 in 1950. The Bay is a port of call for small coasting vessels, and a supply point for the ranches in the interior. It is 20 miles to La Presa. 3 miles up the arroyo "from the beach are a ruined dam, an irrigation ditch, and an old orchard of orange and lemon trees, all that remains of the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Dolores," the authors of the Lower California Guidebook tell us. "Los Dolores was reduced to the status of a visiting station after the move to La Pasión. It was reestablished as a private ranch early in the 19th century. Here you can get guides for hunting trips. There are mountain sheep on the higher slopes a day’s ride above Los Dolores."28 They go on to give us the legend of El Mechudo, the long-haired man: The Indians were diving for pearls near the high, rocky cliff of El Mechudo. Most of the Indian divers were good Christians, promising the Virgin the best pearl of the day, but there was an Indian who said he would rather have the protection of the devil. He found a great black pearl, and dived again, but didn’t come back to the surface. His companions found him drowned with his leg caught in a giant clam, and his long, black hair waving in the current about him. John Steinbeck, who had traveled in the Gulf with his friend, Ed Ricketts supposedly heard this legend and developed it in The Pearl of the world, which appeared in Woman’s Home Companion in December, 1945.29 But if this is so, and the story is, indeed, set in La Paz, Steinbeck exercised a good measure of poetic license, for little or nothing remains of the original legend. The main north-south highway went from Santo Domingo near present-day Ciudad Constitución, down the west coast, through the dry lakes to Buena Vista and then El Refugio, Santa Fe, Guadalupe to Conejo.30 The forerunner of the present-day highway had been inching north from La Paz since the 1920s, and it was possible to cut over to it. Travelers considered this stretch of the road both lonely and difficult due to the sandy conditions. One turn off went east between present-day Pozo Venancio and Santa Fe following the arroyo to the highway.31 But it too was sandy and difficult with many different tracks. There was another side road from El Refugio to San Luis. The road then headed past El Plátano and Iritú and then split. The branch to the right which was the main road went past Las Tinajas, El Obispo, Punta del Cerro and El Pilar to join the highway at Pénjamo. The branch to the left past El Paso to La Presa and La Pasión. La Presa is described at this time as having 15 acres of corns, beans and alfalfa.32 And at La Pasión several springs are dammed to form a pond.

Marquis MacDonald, Glenn Oster, American Travelers Marquis MacDonald and Glenn Oster, who took the road from San Luis to Los Dolores in 1950, described it as "the worst stretch of road on our entire trip, as it was merely a stairway of stone ledges and we lurched along at a mile an hour, expecting the Jeep to break in two at any moment. After we had experienced several hours of such driving, the road came to a dead end on the rim of a steep arroyo. Dismayed, we were ready to turn back when we saw a large burro train approaching us from across the arroyo. The donkeys were heavily laden with bulging panniers of oranges, and the driver told us they were from the village of Dolores on the Gulf and headed for faraway La Paz. We were heartened when the driver informed us that we were less than a mile from a ranch across the arroyo. We had thought that the mission of Dolores del Sur was probably located at the village of Dolores, but the driver told us that Dolores was his home and there were no ruins of any kind in that section. After questioning him extensively, we quickly walked to the ranch across the arroyo, Rancho La Presa. "We were overwhelmed by the great size and architecture of this ranch house, which was Grecian with seven large pillars supporting each side of the red tiled roof. The walls were of massive hewn stones, three feet thick. The owner, a wizened man of ninety, informed us that although he was born nearby, he knew nothing of the history of the house and that it was old when he was a boy. At first we thought it was probably a mission or a chapel, possibly even Dolores; but an examination of the interior discounted this impression. However, this building was coeval with the missions and what secrets it must hold! The franciscan records do mention a ranch near Dolores that served as a chapel after Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga were closed down and this was probably it.33 The ancient rancher told us that we were the first Americans to ever visit the region and the first ones he had ever seen. "After some difficulty conversing, due to the deafness of the aged rancher, we elicited the information, to our dismay, that there was no mission nor ruins in the vicinity. Fortunately, at about this time, his son returned. ""There are no mission or ruins in this area," he told us. "There is a building a couple of miles east which is a chapel - ‘La Capilla.’ " "We were discouraged, but with nothing better in mind, we decided to take a look at it anyway. We passed the washed out remains of a large dam, which gave the ranch its present name. After rounding a turn in the arroyo, we were agreeably surprised to see the tumbled remains of a well-constructed stone building that was undoubtedly our elusive Dolores del Sur. Further inquiry confirmed our opinion when it was gleaned that the small arroyo, on which the ruins are located, is known as "La Pasión," an affectionate sobriquet bestowed on Dolores by the padres. We found only one wall standing and the rest of the stones tumbled in a forlorn heap as if demolished in an earthquake. For many years the bell of this mission reposed at the ranch house, but unfortunately for us, it had been sent to La Paz only five days before our arrival."34 Traditional Rancho Life Traditional rancho life still goes on in the Guaycura nation today. An account by Miguel del Barco, for example, of the structures built in Jesuit mission days could serve as a blueprint for the palapas still being constructed: forked poles are set in holes in the ground to carry rafters split from palm trunks which, in turn, carry roof rafters to which a thatch of palm leaves is tied, or these days, often nailed.35 Half walls are made of carrizo, the local bamboo-like grass.36 This kind of construction was, itself, probably brought from Sinoloa by early mission workers.37 Other aspects of traditional life can be found in the La Pasión area, as well: the small herds of cattle, the goats that are led out to browse in the surrounding countryside, the kitchen gardens and orchards, still occasionally irrigated by acequias, or irrigation channels cut in the ground, or built up, some leather-working, one of the last surviving sugar-cane mills, and so forth.38 And the physical challenges remain, as well: the summer heat, the years’ long droughts, the occasional flash-flood that carries orchards and roads away, etc. And the people outback retain the admirable qualities that travelers over the years have remarked upon: a sense of independence and dignity, a well-cultivated open hospitality in the midst of limited material circumstances, and warm ties to family and community. All these things lend an attractive timelessness to the sierra because a person, at least for a moment or two, can imagine that he or she is back in the middle of the 19th, or even the 18th century. But we can’t romanticize this traditional rancho life too much, for it had its share of problems. The preservation of traditional life came at the price of a certain isolation. There was a lack of formal education, and a focus on practical matters, perhaps to the detriment of folklore and visual imagination. The traditional ways were preserved, but there was not a lot of innovation.39 And isolation, which women suffered from more than the men, also led to a certain amount of inbreeding, and illegitimacy.40 But the essence of rancho life remained intact. The men and women of the sierras and plains would build their houses, raise their goats and cattle for meat, cheese, and market, grow their gardens and plant their orchards where possible. They married, raised their children, looked after their extended family, had time for their friends, and met their needs directly and simply with dignity and independence. And so these ranchos became imbued for these reasons with a certain magic in the eyes of travelers both old and new. Each person found his own distinctive place in family and community. They had "an astonishing amount of personal identity."41 But Crosby, writing in 1981, goes on to say: "Only with the coming of the roads and a concurrent surrender to the desire for manufactured objects has this pride withered somewhat. As contact with modern life spreads, the mountaineers are more and more bowing their heads and accepting the roles of poor and unworthy people."42

The Twilight of the Ranchos? This traditional life, like its counterparts all over the world, is facing a new and difficult challenge with the advent of the transpeninsular highway and the roads that now reach all but the most physically inaccessible ranchos. A trip to town that was once measured in days is now - despite the frequently poor condition of the roads - measured in hours. The multi-generational families of the ranchos are under signifcant pressure. The children go off to school, but distance often requires that they board there for the entire school week. Young people go to town to attend secondary school or the university. And the roads have drawn the sierra more deeply into our cash economy, for roads mean old pick-up trucks, gasoline, and parts at prices equal to or more than those found in the United States. The lure of town and its physically easier way of life, and its more abundant social and economic opportunities grow stronger. Life in the sierra needs more money, and jobs are hard to come by and ill-paid. This need for money leads to a heavier exploitation of the sierra resources. Mesquite is burned to make charcoal that is sold for a few pesos. The coasts are more heavily exploited for fish and shellfish to sell in town, and men work more frequently off the ranchos, and women suffer a new kind of isolation, for rancho life is no longer at the center of everyone’s lives like it was before. In short, the very center of gravity of the small ranchos and communities is shifting to places like La Paz, or Ciudad Constitución. One man in the remote sierra told us in a half-joking way that when his daughter grew up she would go to Cabo San Lucas and make feria rápida, that is, quick money. We saw before how the Guaycuras under the impact of the missionaries’ desire to create European-style village had suffered the loss of their traditional ways, and with it a loss of their own center of gravity and self-identity. Ironically, once the missions were gone, or the mission workers and soldiers could vote with their feet, these small villages were, in fact, created in the form of the traditional ranches, and they have endured for 200 years. Now they, in turn, are losing their equilibrium, and this is effecting the very qualities of independence and self-reliance and self-identity that have been so long admired. Will the people in the sierra end up feeling like the poor country cousins left to stagnate on their ranchos while real life goes on in Cabo San Lucas or Tijuana or Los Angeles? Will they suffer a certain loss of soul that will lead to increasing alcoholism, illegitimacy and domestic violence? This is a process is still playing itself out all over the world. If the Guaycuras couldn’t resist 18th century European civilization, do the people of the sierras have a chance to resist the 21st century world of Cabo San Lucas? From our vantage point we can see the limitations of the Jesuit missionaries’ social-theological programs, but can we see the limitations of our own society, and what will be lost when the traditional life of the ranchos is no more?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Complete List of Books, DVDs and CDs