Clemente Guillén

’s calculations of 1730 and 1744 supplemented by data from elsewhere allow us to get a sense of the makeup of the Guaycura nation, and unfortunately, witness its decline.

The 1730 Informe

Guillén

’s informe of 1730 gives us a detailed census of the mission of Los Dolores, still at Apaté.Mission of Our Lady of Los Dolores from the

19th of February, 1722 to the 19th of June, 1730

| Rancherías | Married | Single | Boys | Girls | Catechumens | Distance leagues |

| Dolores | 34 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 0 | centro |

| Akiá | 10 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 20 l |

| Cunupaqúí | 28 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 1 | 26 |

| Deverá | 18 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| Aripaquí | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Atembabichí | 18 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 8 |

| Atiá | 12 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Cogué | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Quaguihué | 18 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| Guachaguí | 12 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 10 |

| Iriguái | 2 | 1 | 16 | 19 | 14 | |

| Cuenyágueg | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 10 | |

| Michiricucurébe | 4 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 7 | |

| Achéme | 4 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Chiyá | 0 | 2 | 13 | 18 | 12 | |

| Achére | 9 | 8 | 14 | |||

| Atiguíri | 1 | 5 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Aniritúgue | 9 | 5 | 16 | |||

| Michiricuchayére | 4 | 4 | 18 | |||

| Hnyaichiri | 11 | 12 | 40 | |||

| 166 | 71 | 160 | 164 |

He sums up the number of his charges:

| Baptisms | 721 | Married | 166 |

| Deaths | 160 | Single | 71 |

| Remaining | 561 | Boys | 160 |

| Girls | 164 | ||

| Living | 561 |

He also estimates the total population of the mission territory at between 1,300 to 1,400. If we add the few catechumens to the number of baptized, we get 728, of which 160 had died, or almost 22%. Some of this attrition is due to tribal warfare, as we saw in this report in the case of the fathers of the boys killed by the Cubí. If we imagine that infectious diseases are slowly radiating out to the distant rancherías from Apaté, and 22% of the population at the time of contact have already died, this would put the total population, at contact, at 1,600 to 1,700.

There are 83 families in this census, and 160 boys and 164 girls, giving us 3.9 children per family. But these figures must have already been skewed by the deaths, and the fact that children are being baptized without their parents being accounted for in the chart. S.F. Cook in his study of the demographics of the Baja California missions, and the impact of disease on their populations, suggests the figures of 3 children per family before contact, and 1.4 after, which is another way of indicating that the figures we have for Los Dolores are distorted by the way they have been assembled.1

Cook also suggests a ranchería size of 100-250 people, while Guillén’s census shows only 28 people per ranchería, or if we correct this figure to account for the people who have already died, 34, which is still very low. But once again, the figures are skewed since they only count the baptized and catechumens. But it is unlikely that the rancherías in this area had numbers anywhere close to even Cook’s lower estimate.2 Guillén tells us, himself, in the 1730 informe how the rancherías, even though they are small, divide themselves up into 2 or 3 shifting groups who live among the cliffs and mountains, and so it is difficult to determine the actual number of catechumens. One day they are at Chiyá, and the next at Achére.

All we can say is that the rancherías in this rugged country were probably smaller than elsewhere, and more fluid due to the low carrying capacity of the land. If we keep our original ranchería figure of 34 and multiply it roughly by the known rancherías shown on Map 2, and add to this number the unlocated ones, we arrive at around 70 rancherías, which at 34 people each would be a total population of 2,380.3

Cook suggests that the carrying capacity of the land in general was 1.3 person per square mile, but this is probably significantly too high if we factor in the barren Magdalena plains and their lack of water. If we estimate the mission area of Los Dolores and San Luis at 5,600 square miles, then we arrive at only 1 person per 2.3 square miles, or .35 persons per square mile.4

Another rule of thumb that Cook employs is the number of children multiplied by 5 in order to get the total population. This would give us 324 children x 5, or 1,620. Cook, basing himself on José de Echeverría in Clavijero estimates that the 6 southern missions in 1729 had baptized 6,000 people, and suggests the following breakdown: 1,000 La Paz, 600 Santiago, 1,200 San José, 500 Todos Santos, leaving 2,700 for Los Dolores and San Luis. If we take these various estimates, we can put the precontact population at somewhere around 2,300-2,500.

1740. Lamberto Hostell, in a letter written to his father, says he brought 700 Indians together in 1740 in the three settlements that made up the mission of San Luis. He gives us the total number of baptized adults and children from July 14, 1737 to Sept. 28, 1744 as 488. Jacobo Baegert tells us that baptisms were still being made in the San Luis mission territory until 1748. Juan Antonio Baltasar in his visit to Mission San Luis on Dec. 9, 1743 puts its population at a total of 180 families. He gives the population of Los Dolores at 200 families. The author of Descripción y Toponimia, writing probably in 1741, puts the population of La Pasión at 200, and that of Los Dolores at 300, figures that we can take as more or less rough estimates.

The 1744 Informe

From August 11, 1721 to August 7, 1744, when Guillén, probably aided by Hostell, composed his 1744 informe, he reports that he had baptized 1,849 adults and children, not a few of whom had been gathered together at La Pasión and San Luis Gonzaga, and many of whom had been carried off to the other life by diseases like smallpox. The present population of Los Dolores was 749. There were 186 families, which accords well enough with Baltasar’s 200 families.

| Mission Station | Married people | Children | Single | Total |

| Los Dolores | 84 | 57 | 18 | 159 |

| Immaculate Conception | 64 | 45 | 15 | 124 |

| Incarnation | 54 | 42 | 16 | 112 |

| Trinity | 32 | 37 | 13 | 82 |

| Redemption | 60 | 48 | 22 | 130 |

| Resurrection | 78 | 46 | 18 | 142 |

He also leaves us figures for the recently started mission of San Luis Gonzaga, as well as the gathering spot of Jesús María at Aenatá and some of the west coast inhabitants.

| Bahia Santa María Magdalena | 96 | 79 | 20 | 195 |

| San Luis Gonzaga | 82 | 80 | 28 | 190 |

| San Juan Nepomuceno | 62 | 55 | 14 | 131 |

| Jesús María | 90 | 82 | 23 | 195 |

| West Coast | 18 | 28 | 10 | 56 |

The 174 families connected with San Luis accords well with Baltasar’s 180 families, and the total population of San Luis is 767. The 1,849 inhabitants of the total area who have been baptized probably represents the vast majority of the people at this rather late stage of evangelization. But if 1,561 are still alive, this means that 16% of the baptized have been lost to disease and other causes, which appears a bit low compared to the 22% of the 1730 figures. If we take the 1,849 baptized and correct it by 22% to account for the losses, we arrive at 2,255, and there are still more people to be baptized (see Hostell below), so we can arrive at a total pre-contact population of about 2,500, which is in rather good agreement with our other estimates. If we imagine a 22% loss by 1730, then we can put the population in that year at 2,000 and the population in 1744 at 1,561 and more still to be baptized for roughly 1750.

If the 1730 data showed 3.9 children per family, which we took as being too high, the 1744 census shows 1.6, which is in rough accord with Cook’s estimate of 1.4 children per family after contact. This decline of the size of the family shows the impact of disease on the Guaycura nation.5

Harry Crosby estimates that between 1744 and 1762, 200 Guaycuras went to San José de Comondú, but they could very well have been baptized and counted on the San Luis mission roles. Hostell in another letter to his father in 1758 tells him that he has baptized 2,000 people, which probably means the 1,849 from both missions, plus some more between 1744 and 1750. Jacobo Baegert tells us that the mission of San Luis during his time had 360 people, but elsewhere he gives us the number of 1,000, which probably was his estimate of the total population of the whole mission territory for the two missions. José de Utrera’s visit of 1755 shows 365 for the whole of the San Luis territory, and 624 for Los Dolores, for a total of 980. 150 lived by the Pacific in 1757.6

Ignacio Lizasoáin gives the following census for Los Dolores and San Luis in 1762:

| Los Dolores | San Luis Gonzaga | |

| Families | 132 | 90 |

| Widowers | 27 | |

| Widows | 34 | |

| Confessions | 369 | 240 |

| Communions | 133 | few |

| Individuals | 573 | 300 |

This gives a total population for the two missions of 873. Lizasoáin’s figure of 300 people at San Luis in 1762 fits reasonably well with Baegert’s figure of 360, which comes from the year 1752.

For 1768 Lassépas7 gives the population of Los Dolores as 450, and the population of San Luis as 310. Palóu tells us that in 1768 the epidemic carried away more than 300 people, which would put the population somewhere around 450. Finally Fray Rafael Verger puts the population in 1772 at 170.

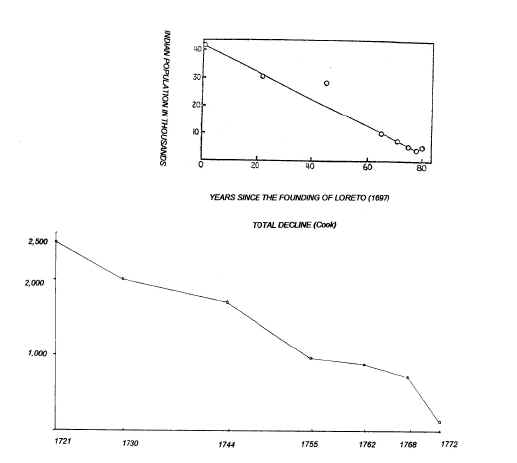

If we take the total population to be 2,500 in 1721, 2,000 in 1730, 1,750 in 1744, 980 in 1755, 873 in 1762, 760 in 1768, and 170 in 1772, we arrive at the following graph of the decline of the Guaycura nation. This decline was undoubtedly accelerated by the 1744 formation of pueblos. This parallels Cook’s graph of the decline of the total population of Baja California, about which he says, “The straight line of descent is indicative of a population loss due to disease.”8 Cook estimates that 30-40% of the decline was due to epidemics and venereal disease.

Disease must have played the major role in this precipitous decline of the Guaycura, although we do not have many details. An epidemic struck San Juan Malibat in 1720-21, and if Guillén brought some of the Monquí with him at the time of the founding of Apaté, they and the Spaniards could have spread disease from the very first moments of the founding of the new mission. In fact, Guillén’s two expeditions of 1719 and 1720-21 may have initiated the spread of disease. And we have not even considered the possibility that infectious diseases could have raced ahead of contact with the Guaycuras coming from early contacts at Cabo San Lucas or the founding of Loreto, and significantly reduced their numbers. We do know, however, that epidemics struck the south in 1742 and 1744 (typhus, typhoid and malaria) and 1748, (measles)9 and it is very unlikely that Los Dolores and San Luis would not have suffered in their turn given their connections with the southern tribes. Baegert’s remarks that the men had difficulty finding wives, and a great number of the women in his mission did not bear more than one child, and most of the children died, could be read as an indication of the spread of syphilis among the Indians, for the disease was already wide-spread in the south. Here we can recall, as well, his comments about the soldiers sleeping with the Indian girls, and the sexual activity at fiestas between the different bands. He also mentions a smallpox epidemic that took place at Los Dolores.

Our somewhat shaky calculations have led to a rather firm conclusion. Infectious diseases, here in the Guaycura nation, let to a precipitous decline of the Indians that paralleled that of the rest of Baja California and throughout North and South America.10

Table 1. The Decline of the Guaycuras

The Jesuit Missionary Enterprise

It has cost us considerable effort to reconstruct the lost world of the Guaycuras of Los Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga, and now it is time to ask a series of questions which, although they will remain in large part unanswered, allow us to ponder the wider significance of what we have been seeing and its connection to our own times.

One way to sum up the Jesuit missions of Baja California is to say that heavenly intentions led to disastrous human results. Or more baldly, the evangelization of the Indians led to their extinction. But this statement has to be immediately qualified and nuanced. It was not the preaching of the Gospel, itself, that led to this destruction, but European contact. If the initial settlement of Baja California had been by the conquistadors, the final result most likely would have been the same, and the road to it much more rocky, that is, slavery or brutal exploitation.

The Jesuits must be allowed their dreams, in this case a dream perhaps inspired by missionary attempts elsewhere, for example, in Paraguay, where they developed much larger and much more highly developed religiously inspired and led communities. The Baja California Jesuit missionary Franz Inama, writing to his sister in 1755, about how the missionaries must care for both the body as well as the soul of their charges, says: “I shall not dwell any longer on this point. You, my dearest sister, have at hand the letters of our missionaries in Paraguay; they will give you an idea of how we administer our missions here in California.”11 Perhaps this is what stood behind Baegert’s market village. It was to be a village where the missionaries stood at the apex of spiritual and temporal power, the colonists were to be held firmly in check, and the Indians grouped in villages around the mission dressed in robes, greeting the new day with their choirs and orchestras, and working in the fields and workshops. It may have been this kind of vision that inspired someone like Bischoff to train the Indians in choral singing.

In many ways it was a beautiful dream which in a place like Paraguay appears to have been much preferable to the alternatives, that is, the treatment of the Indians meted out to them by the colonists, and it was a dream to which the Jesuits sacrificed themselves out of a desire to serve God and their fellow men. But such utopian dreams soon run up against the hard reality of unruly human nature, and all its baggage.

One piece of this baggage was the use of force. It certainly goes against our modern grain to see that force was an integral part of the missionary program. But religious liberty as we know it today is a hard one, and a still precarious achievement. We need to judge the Jesuits by the very different standards of their own times. How far, for example, did they depart from the prevailing European norms, both Catholic and Protestant? How far did the Jesuits depart from Spanish Catholic practice with the Inquisition still operational in Mexico City?12

These questions are closely intertwined with a wider issue, which was how the conversion of the Indians was intimately connected with making them subjects of the crown and converting them to European ways. While this is an issue that has been widely discussed in Catholic missionary circles in the 20th century, and especially in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, we can hardly expect our 18th century Jesuits to partake of those views.

Baegert’s village, as well as the missions with their pueblos, were patterned after the missionaries’ European’s homeland. There is certainly a very literal paternalism in all this, and a Eurocentric insensitivity to native cultural values. But again, we can hardly fault the Jesuits for not sharing our own modern sensitivities. They certainly saw no incongruity in imposing on the Indians both religious and social values in the name of their religion and its civilization. Part of the dearth of information we have on the religion of the Guaycuras is due to the fact that it was rather inconceivable to the missionaries of Los Dolores and San Luis that this religion had an intrinsic value in itself. Much the same could be said about the Guaycura language. Why preserve it, save as a practical tool or as a curiosity, when the Indians could learn Spanish and become part of the wider civilized world?

By way of reaction

, it would be wrong to imagine that the missions had nothing to offer the Indians. They had a whole complex of technologies from the most basic like reading and writing and agriculture to the domestication of animals and ideas on law enforcement aimed at eliminating the warfare among the rancherías. Most of these things we take for granted, but we base our lives on them, and they could not fail to attract the Indians, or perhaps we could say the Indians were at once attracted, fearful and threatened by this overwhelming display of proffered beneficence and military prowess. Christianity at its best, proclaiming the love of God and neighbor and a life to come, could also be highly attractive, expecially when it was embodied in the loving kindness of a missionary. But Christianity in the Jesuit missions came dressed in European clothes. The Jesuits who had to be counted among the best educated men of their times could not conceive that the Indians and their way of life had really something to offer them in return. What prevented this was not only a difference in their respective technologies, i.e., a stone knife vs. a metal one, but went much deeper. There was a profound cultural and psychological divide, as well.The Hunter-Gatherers

The Guaycuras were still hunter-gatherers like the whole human race once was. They may have even been the remnants

, at least in some of their cultural traits, of an early wave of immigrants to the Americas, an issue we will consider later. And it would be surprising if the Guaycuras, despite their relatively isolated geographical situation, differed fundamentally from hunter-gatherers all over the world. Yet it is possible that the poverty of their environment had impacted and even retarded their development, and during the preceding century epidemics could have sapped their vitality.But it would be wrong to see the Guaycuras only through Baegert

’s eyes, and to imagine that they were a particularly degenerate and savage lot. So much is in the eyes of the beholder. The Bushmen in southern Africa are an instructive parallel. Indeed, Baegert compared his own people in California to Hottentots,13 and it is likely that this was a catch-all designation that included the Bushmen, as well. The Bushmen appear to be a remnant of a people who once inhabited large parts of Africa, and a comparison between the Guaycuras would be instructive, for it would allow us to see more clearly what was particular to each, and what were wide-spread traits common to hunter-gatherer cultures. The Bushmen, for example, constructed flimsy brush and grass huts almost invisible to the outside eye. They could gorge themselves on meat, when they had it, and sleep away the rest of the day. They went about mostly naked, and had a minimum of possessions: bows and arrows, digging sticks, water containers, etc. By Baegert’s standards, they were dirty, sometimes splashed by blood from the hunt, and had a distinctive smell. They made cordage out of aloe fibers from which they made netting. All traits we saw among the Guaycura.The Bushmen were natural

, instinctive superb hunters who were expert trackers - and the Guaycuras, no doubt, were as well. The Bushmen rehashed their hunting and gathering forays around the campfire with the whole band, and so each member of it carried an intimate local geography of individual plants and trees and rocks, and the paths animals would take in flight. They knew when and where to seek out the fruiting plants and to gather seeds. And we can with some confidence attribute all these qualities to the Guaycuras, Baegert, for example, recounts how instead of discussing spiritual matters, they would go on and on about the path taken by a wounded deer. And the hunting of large game animals stood at the apex of their material culture, and had a religious meaning, as well. In this regard it would be well to recall the splendid images painted on the walls of the rock shelters in the Sierra de San Francisco. It is not surprising, therefore, that both the Bushmen and the Guaycura collided with a world that kept cattle. They both had reputations as incorrigible cattle slaughterers, and suffered a great deal for it. But at the root of this conflict was not just stubbornness and maliciousness, or simply a matter of food on their part, but the imperatives of the world of the hunter. In this light it was asking a lot for them to readily understand that this steer was not to be killed and eaten when it was encountered.These kinds of comparisons could be extended into other areas of life

, as well. The Bushmen, for example, sometimes killed newborn children. Even the non-weddings of the Guaycura that Baegert described find some sort of analogy in those of the Bushmen in which the parents of both the bride and the groom, and in fact, no adult, attended, but only young people. In this case it was the question of a taboo. Among the Bushmen, as well, as find occasional polygamy, as well as a taboo that restricted contact between the husband and his mother-in-law, and the wife with her father-in-law. And we have stories of Bushmen dying in prison because of their need to be free and roaming the earth, which can make us think of the Guaycuras with their dislike of staying in buildings. Both the Guaycuras and the Bushmen literally slept on the bosom of the earth, in intimate contact with the sun and the stars, and wandered over land that was distinctively and intimately theirs. These kinds of parallels could be extended to embrace other qualities and other societies, but our purpose here is to break the negative spell that Baegert wove around the Guaycuras and to see them afresh.When the Bushmen are seen through the eyes of a poet like Laurens van der Post

, they become a magical people close to the earth and each other, swiftly running through the desert in pursuit of a wounded antelope, or gathering roots, or sitting around the fire telling stories. And even more down-to-earth accounts, like those of Jens Bjerre and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, of the Bushmen have found a way to be in general sympathy with them.14 But none of our Jesuits was a poet in the sense of van der Post, or even could be called sympathetic, and it is hard to imagine one of them sitting in a rock shelter and gaining the confidence of their people, and even their shamans, and trying to truly understand how these people saw the world and what they believed in.All this is not to turn the Guaycura into paragons of virtues

, into Rousseau’s noble savages that Baegert mocks in his Observations.15 If we were to sit in those rock shelters of the Guaycuras today with them, there would be, no doubt, many things that would offend our sensibilities, and it would take all the good will we could muster to try to understand where they were coming from. Along with the basic accomplishments of civilization, we take for granted a certain kind of psychological differentiation. Because of it, we are capable of long sustained efforts to accomplish future goals, as well as long sustained acts of hostility and destruction that would boggle the minds of so-called more primitive men. We live very much in our egos and their desires and antipathies, and it is hard for us to conceive that everyone does not share this kind of psychological make-up. Yet, even by way of hypothesis it is salutary to try to imagine hunter-gatherers like the Guaycura living in another psychological world. In that more unconscious and collective world the individual did not push himself forward in the same way. Indeed, he didn’t even exist in the same way as an individual. He lived within small family-based groups, not only physically, but with a psychological commonality that is hard for us to imagine. This was a world of vibrant immediacy without much thought given to the past or future. The earth was not seen as a potential source of resources to exploit, but an encompassing mother that sometimes showed favor, for example, at the time of the pitahaya harvest, and sometimes turned her face away. Each day, while it would appear monotonously like the day before to the European observer, was a new day. It was simply the way life was and always had been, and therefore there was no need for elaborate calendars. If there was a time of scarcity, it was shared by all, and there was always abundant time to tell stories, make jokes, and be with one’s friends.Again

, this is not to paint some idyllic picture of man in harmony with nature. We know enough about the Guaycura and the world they lived in to see that that would be false. Rather, it is to say that the Guaycura did, indeed, live in another psychological world, and could only be judged harshly by someone like Baegert. He thought that their language was primitive, and they lacked the power to reflect and to express abstract notions. In a certain sense this was true, but he did not comprehend why it was true. For him, their refusal to work and to be punctual, and to say their prayers, to build houses, and on and on, was all evidence that he could use to condemn them. But for their part, work wasn’t really distinct from life, itself. They hunted for their food; they consumed it, they took their ease, they amused themselves, their language was concrete and immediate because that was the world they lived in. They were capable of creating ways to describe new experiences, and their children had the innate capacity to develop the differentiated consciousness of the Spaniards, but the Guaycura lived a very different kind of life, a life much closer to the first humans, an inner world that remained closed to Baegert.But what about us? Are we capable of understanding them? Certainly the track record for the so-called civilized nations in their encounters with hunter-gatherers is almost unanimously bad. We can hardly say that we have been ready to learn any lessons from them. We can hardly say

, either, that we know how to relate to the earth in a positive and non-destructive way. We imagine that these more primitive peoples would want nothing else than to be just like us. But this is not convincing. Do hunter-gatherers accumulate possessions beyond their needs? Do they fill themselves while their immediate neighbors go hungry? Do they kill animals they cannot eat? Are they so busy working they have no time to be with their friends? I am not suggesting that we go back to being hunter-gatherers, but only that we try to look at the Guaycura with different eyes and see if their simplicity has something to teach us about our own, often over-complicated lives, that ruin the earth to no real purpose. We need to reread Baegert’s sarcastic remarks about the Guaycura from the perspective of seeing them as men and women who live close to the earth and each other, and did not share many of our preoccupations. Were the Guaycura lazy? They walked about all day and were remarkably fit, but they didn’t do well with the regimented program of work at the mission. Were they thieves? This was one of the chief points of friction between them and the missionaries, as we saw. But the thievery of cattle has to be seen within the wider psychological perspective we are trying to develop. You are asking a great deal of a hunter to suddenly change the inner structure of his psyche and look at the missionaries’ steer in a very different way than he looks at a deer, or a turtle. In his mind the earth gives a momentary opportunity to satisfy his hunger, and he takes it. Tomorrow had to take care of itself.The historical accounts of the Baja California Indians state that they had no dogs. The Spaniards

, in fact, were amazed at how afraid the Indians were of dogs. But again, we need to search for the proper vantage point to understand this. It is entirely possible that for these Indians the domestication of animals appeared as a magical thing. The Indians were not afraid of dogs simply as animals. They were used to dealing with mountain lions, for example. But it must have been an amazing and powerful thing to encounter for the first time animals that were somehow under the power of men, or were even in some way human, themselves. Therefore the Indians sometimes treated the mules of the soldiers and missionaries as if they were human, in one case actually giving one of them a burial. Perhaps the same process is at work. We are so used to the domestication of animals that we give it no thought. Perhaps to gain a sense of what the Indians felt we would have to imagine a wild animal coming up to us without fear.The picture that is emerging is one of a fundamental difference in perception. The Jesuits had all sorts of good intentions backed up by discipline and the power of organization. But they also had a very definite program to which they were determined to fit the Guaycura in. The Guaycura lived in a very different psychological universe

, and the contact between these two different worlds set off forces that neither side could control.We can return now to the question of why Baegert

, and probably the other missionaries, considered the mission-raised Indians the worst and most malicious. Let’s look at the Ascension Day murder again. We know that according to Baegert adultery was common among the neophytes of San Luis and Los Dolores. He laments, for example, how they go to confession, and immediately go out and commit adultery.16 Why, then, does the young man who committed adultery kill the husband who threatened to report him? Why doesn’t he shrug and ignore it like so many of the other Indians seem to have done? Jealousy might account for part of his motivation in acting this way, but he very well might have been ashamed. Perhaps he was actually changing under the impact of having been brought up in the missionary’s household. Then he would among the first to suffer the pangs of the transition from the old hunter-gatherer way of life to the new one, and this transition would be accompanied by disorientation, for he can’t return to the old ways, which he might even despise, but he can’t go forward and truly enter the new world of the missionary and the Spanish workers who, in any event, probably consciously or unconsciously, make him feel like he will always be an inferior member of their world. In short, he could suffer a certain psychological loss of soul, a loss of identity that could lead to this kind of destructive behavior.We can make the same kind of analysis in the case of the murder of Vicente

, the Indian boat captain from Sinaloa about whom Baegert tells us, that besides his food, he was paid a salary of 84 francs in French money.17 In this way he could easily be seen by the Guaycuran rowers as standing on the next step of the ladder that stretched from their world to that of the Europeans and become the target of their hidden resentments and feelings of inferiority.The efforts of the missionaries to save the souls of the Guaycura had led by misadventure to this kind of psychological loss of soul. This same tragedy has taken place in many times and in many places where hunter-gatherers have come into close contact with European civilization. They lose their center of gravity and succumb to alcoholism and other forms of destructive behavior. Even if the Guaycura had physically survived the infectious diseases

, they would have faced the hurdle of this often fatal psychological dis-ease.Infectious Diseases and Death

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Jesuit missionary enterprise was the fact that the very establishment of the missions and their pueblos which gathered the Indians together was the conduit for the spread of infectious diseases that carried the Indians off. The Jesuits could not

, of course, have been unaware that the Indians were dying as the missions advanced. But how conscious were they of the role they were playing in spreading disease? Here we face another series of questions that we can only begin to ask rather than answer. Just what did the educated man in Europe know about infectious diseases in the 18th century? What did the Jesuits know? Clearly, Baegert knew that smallpox could be spread by contact, as we saw in the incident of the Spaniard setting off an epidemic by giving an Indian a piece of cloth. But he wondered why the Americas were being depopulated even in areas where the Europeans had not yet gone, by which we saw that his understanding of infectious diseases was limited. To put their understanding in context, Edward Jenner’s experiments with vaccinating people with cow pox were carried out in the late 1780s and early 1790s. Luis Sales, the Dominican missionary in Baja California who served between 1772 and 1790, tells us how he was present, perhaps in 1781, in San Ignacio when its missionary Crisóstomo Gómez inoculated the Indians against smallpox with good effect.. This would have probably been an inoculation with smallpox, itself, a practice that was being used in Europe earlier in the century, rather than with cow pox, as in the case of Jenner.18Beyond this question of the medical knowledge of infectious diseases

, what was the attitude of the Jesuits and the Indians, themselves, about death? We can be sure that it didn’t coincide with our own. They were on more intimate and direct terms with it. Infectious diseases routinely carried off people both in the old and new worlds. The Guaycuras, themselves, showed a certain calm in the face of death. We can forgive, therefore, the Jesuits their imperfect knowledge of infectious diseases, but not Baegert his comment on the demise of the Guaycura: "the world loses none of its glory."Mission Theology

We have a final series of questions

, the answers to which would involve us in ever-widening circles of research. The Jesuits shared with the rest of the Catholic Church of the time a theology that said: "Outside the Church there is no salvation." And with that went the necessity of being baptized. This theology went back many centuries, and had an in-built weight of tradition that resisted easy change, and we can see it in operation in the Jesuit missionary practices in Baja California in terms of the imperative to baptize, especially those in danger of death so they could enter the kingdom of heaven. It is also expressed in the rather strict rules that existed for both the missionaries and Indian leaders to make sure that no one died without the spiritual assistance of the missionary.More generally

, the missionaries sometimes leave the impression that they were more interested in the spiritual health of their charges, i.e., that they would meet the basic admission requirements for heaven, than they were in them as human beings. It was as if they were keeping score about the value and effectiveness of their work by means of what we could call heavenly calculations. Hence, the carefully kept mission registers - which unfortunately seemed to have disappeared in the case of Los Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga - the reporting in the informes, and so forth. What I am suggesting is that a genuine desire on the part of the missionary for the spiritual well-being of the Indian could become narrowed in a quite human way by a series of factors: his negative judgment about the Indians’ state of civilization, the pressure of a "no salvation outside the Church" theology, and so forth. The Indians could then become souls to save rather than people who needed to be first understood, both humanly and religiously. The missionary must have had a certain affection for his neophytes, but it was an affection that had to struggle to bridge the psychological distance between the two worlds and was subject to theological imperatives.But the

"no salvation outside the Church" theology was not monolithic. It coexisted with a sense that God willed all people to be saved, and it was the Jesuits, in fact, who were to be numbered among the more progressive theologians when it came to striking a balance between these two dimensions of the tradition. The Jesuit theologians, for example, Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), Francisco Suarez (1548-1619), and Juan De Lugo (1587-1660), all of whom taught at the Jesuit Roman college, played an important role of modifying the more rigid kinds of "no salvation outside of the Church" theology, and the Order had been locked in a struggle with the hard-line Jansenists over the matter. Without needing to go into the intricacies of these various theological positions, we can say that the more progressive theologians under the impact of the discovery of the New World and the realization that there were millions of people who had never known Christ, had tried to show how these people could belong to the Church by desire and good works, and thus reach salvation.19It is another matter

, of course, to determine how much of these progressive theological attitudes emanating from the Roman college filtered down through the ranks of the missionaries and effected our missionaries in the Guaycura nation. It is certainly hard to imagine that they saw much salvific significance in the good works and religious rites of the Indians, which rites they so determinately tried to stamp out, or they imagined that the Indians in virtue of these works or desire were already on the road to heaven. Hence, the importance of those stories in which the Indians fall sick, receive spiritual aid, and die, and the missionary can be morally certain that this person, at least, has gone to heaven.Another dimension of this same theological complex was in the area of sacramental theology. Could the Indians be allowed to receive the Eucharist? Once again

, we are in another theological era, this time one in which the reception of Holy Communion was much less frequent. Further, we should not forget that earlier in the New World a debate had raged whether the Indians even had spiritual souls, a debate that had ended with the affirmation that they did. Baegert’s theology must be seen against this background, and this is, perhaps, why he affirms that the Indians are capable of reaching European levels of civilization if only they are given the proper education.20 The question of the reception of the Eucharist of the Indians was compounded by their need to go to confession and have a firm intention to avoid sin in the future. For Baegert, this was a dilemma, as we saw, for the Indians confessed and then went right back to their usual sexual sins. And so he tried to resolve the problem by absolving them as if they were in danger of death, i.e., they were going to leave the confessional and go off some place where they might die without spiritual aid. But as the statistics of Lizasoáin showed, he continued to have this dilemma and appeared to resolve it by only infrequently allowing the Indians to receive Communion. In this he was more rigorous than his fellow Jesuits, and his own theological tendencies appear to have always run that way. On the boat coming over from Spain, for example, he had engaged in discussions of moral theology with one of his fellow Jesuits who thought Baegert’s opinions too rough, and had called him "half a Jansenist."21Even Hostell

, who was certainly more positive about the Christian life of the Indians, would write to his sister who was a nun in 1743: "What a joy it is, my dearest sister, to see with one’s own eyes, those who only a short while earlier, oblivious of their final destination, lived like brute animals, without hope of eternal felicity, wandering about in the desert, now gathered in Christian communities, knowing God, loving Him and praising Him, leading a pious, holy and edifying life superior to that of the old Christians in Europe! What a consolation that many souls, not only of innocent children but also of adults should depart from our hands, as it were, shortly after receiving baptism! They are prepared by us to face a happy death as Christians leaving this world for everlasting bliss in the next, a felicity of which they would have been otherwise eternally deprived."22For Baegert the whole issue was complicated and intractable. He seriously wondered how many of his Indians would be saved

, especially after seeing them commit adultery right after confession, so he says: "This is the cause o my joy when little children die. It is also my strong fear, if it is true what Saint Xavier wrote in his message to Francis Henry without hesitation, i.e., that only a few Indians who live longer than fourteen years go to Heaven."23 But then he logically follows up, and asks himself whether these people should have been baptized in the first place: "But should we not then given these people holy baptism, because it is impossible through man’s means to give them the deep recognition of it, its secret and necessity for them to accept baptism out of an inner love for God?"24 One horn of the dilemma is that the Indians are in peril of salvation if they are not baptized, but the other is that they need the proper moral dispositions to understand baptism and what it implies, and freely accept it. Further, if they are baptized, then their failure to live up to its moral requirements again puts them in peril of salvation. Baegert concludes that he is happy that everyone in his mission was baptized before he got there: "for I would not know what to do and how to judge the capability and disposition which are necessary for the baptism of an adult person."25 Therefore, he takes a certain kind of consolation in the fact that in the 154 children he had baptized, up until September of 1761, some 90 had died.26 We certainly have difficulty in sympathizing with this perspective, but it worthwhile trying to understand it. On top of all this, he tells us that Juan Bischoff, his predecessor at San Luis who now works among the Cochimí, has told him that his Guaycuras are better than his Cochimí.27