Forgotten Mission Roads

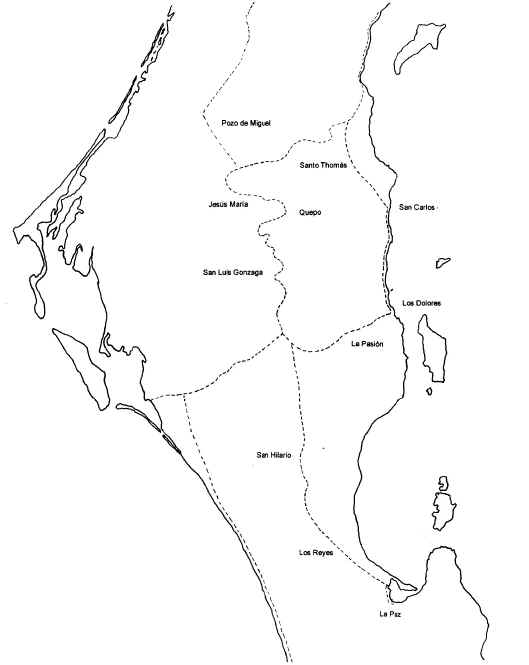

We can sum up the Jesuit mission era geography and its roads in Map 7 and its accompanying charts

, which also serve to introduce us to the age of the ranchos, for they cover later journeys that we will soon become acquainted with. Note that the west coast road from the south and Todos Santos first appears on our charts with the 1867 journey of William Gabb, but it probably existed earlier.

Map 7. Forgotten Mission Roads

Table 2: The Central Road |

|||||||

| 1719 Guillén Expedition to the Bahía de Santa María Magdalena | 1720 Expedition of Guillén starting along the Gulf | Esteban Rodrígues 1741 | Lizasoáin's Journey Feb. 1762 | Longinos' Journey 1792 | William Gabb 1867 | The Map of 1902 (in the Pablo Martínez Archive, La Paz | Modern Place Names

(places appearing on 20th century printed maps) |

| Pozo de Miguel | El Pozo de Miguel | ||||||

| Loreto | Loreto | Loreto | Loreto | ||||

| Bonú | Bonó | ||||||

| Nautrig | Notrí | Notrí | |||||

| Chuenqué Grade | Cuenca Rancho | Chuenqui | Chuenque | ||||

| Juncalito (reconstructed) | Juncalito | ||||||

| San Juan Malibat | Malibat | Liguí | Liguí | ||||

| Playa al

Rincón, Rincón del Marquéz |

|||||||

| Aripité | |||||||

| (missing) | |||||||

| …omaja (partially missing) | Tecomaja | ||||||

| Pemeraquí | |||||||

| Sierra de Santa Ursula | |||||||

| Promontorio de San Nicolás | |||||||

| Santa Cruz Udaré (here begins the land of the Guaycuras) | Santa Cruz Udaré | Santa Cruz | Santa Cruz | ||||

| Cunupaquí, a ranchería in the area but not on the route of the expedition |

Cunupaqui Arroyo | ||||||

| El Paso | El Paso de Santa Cruz | ||||||

| El Tulillo | El Tulillo | ||||||

| La Relumbrosa | |||||||

| La Trinidad | |||||||

| Wash of Santa Perpetua | |||||||

| San Juan de Dios Cuatiquié | |||||||

| Santo Tomás Anyaichirí | Anyaichirí | Andachire | Andachire | ||||

| Candapán | Candapán | ||||||

| Onduchah | |||||||

| Los Mártires de Aquirí | |||||||

| Quatianié | |||||||

| San Gregorio Quiairá (Quiapa) | |||||||

| Jesus Maria Aenaté | Jesús María | Jesús María | Jesús María | Jesús María | Jesús María | ||

| Los Cerritos | Los Cerritos | Los Cerritos | |||||

| San Vicente Tiquenendegá | Fiquenendegá | ||||||

| Santiago Quepoh | Santiago Quepoh | Quepo | Quepo | San Miguel de Quepo

and San Dionisio de Quepo |

|||

| San Clemente Querequaná | San Clemente Querequaná | Querequana | |||||

| San Andrés Tiguana | San Andrés Tiguana | Tiguana | Tijuana | ||||

| Qutoibo | |||||||

| San Borja Cutoigué | San Borja Cutoigué | ||||||

| San Cosme Codaraquí | San Cosme Codaraquí | ||||||

| El Ranchito | El Ranchito | El Ranchito | |||||

| El Frijol | El Frijol | ||||||

| Palo del Rayo | Palo del Rayo | ||||||

| San Damián Chirigaquí | San Damián Chirigaquí | Misión San Luis | San Luis | San Luis | San Luis | San Luis Gonzaga | |

| San Nicolás | San Nicolás | ||||||

| Plátano | El Plátano | ||||||

| Iritú | Iritú | ||||||

| Aniritugué La Encarnación | |||||||

| San Francisco de Buena Vista | |||||||

| San Gabriel Cuedené | Cuedené | Cuedan | |||||

| San Joseph Adague | |||||||

| Anirituhué | Iritu? | ||||||

| Aripité | |||||||

| Jesús Remeraquí | |||||||

| Chiyá | La Pasión (Chiyá) | La Pasión | La Pasión | La Pasion, La Capilla | |||

| San

Marcelo Pacudaraquihué |

|||||||

| Las Liebres | Las Liebres | Las Liebres | Las Liebres, abandoned

ranch near Punta del Cerro |

||||

| Los Padarones | |||||||

| Gui | Agui? | ||||||

| Caracol | |||||||

| San Isidro | San Isidro (adjacent to La Junta) | ||||||

| San Saturnio | |||||||

| La Junta | La Junta near San Isidro | ||||||

| San Hilario | San Hilario | Hilario | San Hilario | San Hilario | |||

| Guadalupe | Guadalupe | Guadalupe | Guadalupe | Guadalupe de la Herradura | |||

| Salto el Conejo | |||||||

| Aguajón | El Aguajón | ||||||

| San Higinio del Guaycuro | |||||||

| La Vieja | |||||||

| San Félix de los Coras | |||||||

| Arroyo de los Reyes | Los Reyes | Salto de los Rey | Salto de los Reyes | Salto de Reyes | |||

| Los Reyes | Huerta de los Reyes | Cajon de Reyes | |||||

| Rodrigues | Rodrigues | ||||||

| Quelele | Quelele | ||||||

| Zacatecas | Zacatecas | ||||||

| Los Aripes | Los Aripes | Los Aripes | Los Aripes | ||||

| Parbellon | |||||||

| Mueles | |||||||

| San Luisito | San Luisito | ||||||

| Zacatal | Zacatel | ||||||

| La Paz | La Paz | La Paz | La Paz | La Paz | La Paz | ||

Table 3: The Gulf Road |

||

| 1720 Expedition of Guillén starting along the Gulf | Esteban Rodrigues 1740 | Modern Place Names |

| Loreto | Loreto | |

| Bonú | ||

| Malibat (the road follows the Gulf) | Liguí | Ligüí |

| Catechiguajá | ||

| San Hilarión Arroyo | ||

| Pucá (Ends Laimón nation, begins Guyacura) | ||

| Santo Thomás | Santo Thomás | |

| Santa Daría Acuré | ||

| San Carlos Aripaquí | San Carlos (the road leaves the sierra and goes along the Gulf) | San Carlos |

| San Gregorio Asembavichí | Tembabichi | |

| Santa Isabel Cahué | ||

| Apaté (the road leaves the Gulf) | The hacienda of Los Dolores | |

| Nuestra Señora de Los Dolores | Los Dolores (the road leaves the Gulf) | the mission of Los Dolores |

| Sierra del Tesoro | ||

| Presentación Devá | ||

| San Martín Quaquihué | San Juan Quaquiguí on the right of the road | The valley and plains of Kakiwi |

| La Pasión (Chillá) (The road joins the Central Route) | La Pasión or La Capilla, the second site of Los Dolores | |

| There is no evidence that this route after this point was ever used. | ||

| San Eugenio Icudairí, Santa Cecilia Caembehué, Santa Felicitas, San Chrysogono Arecú, Santa Catalina de los Miradores, Los Desposorios de Nuestra Señora, San Andrés del Paredón, San Saturnino del Pedernal, Santa Bibiana de las Averías, San Xavier de las Batuecas, La Paz | ||

Table 4: From the Central Route to Bahia de Santa Maria Magdalena |

||

| 1719 Guillén Expedition to the Bahía de Santa María Magdelena | William Gabb 1867 | Modern Place Names |

| San Luis | San Luis Gonzaga | |

| San Joseph Adagué | ||

| Santa María Tacanopá (Tacanopare) | ||

| San Joaquín | ||

| Santa Ana del Espanto | ||

| Santa Isabel Tipateiguá | Tipatehui | |

| Buena Vista | Buenavista | |

| San Benito Aruí (Aruiaquí) | ||

| Santa María Magdalena | Bahía de Magdalena | Bahía de Magdalena |

| La Salada (Gabb then travels inland down the Pacific Coast) | ||

| La Palma | ||

| Agua Colorado | probably formerly in the area of El Estero | |

| Arroyo de Guadalupe | Arroyo de Guadalupe | |

Rancho San Luis

The transition from the land of the Guaycuras to the age of the ranchos started almost immediately after the Indians of Los Dolores and San Luis were exiled. Francisco Palóu, as we saw, recounts how José de Gálvez sent the Guaycuras on their way, and he goes on to tell us that mission San Luis was turned into a rancho: "The family of the discharged soldier Felipe Romero, with all his children, was moved to San Luís, he being given possession of the land. All the necessary vestments were left for that church so that Mass might be said whenever the missionary father of San Xavier could go there; and it was ordered that when there were two missionaries one of them should go once a month to say Mass."1

Many years later in 1857

, Ulises Urbano Lassépas, trying to defend the land titles of the Baja Californians, wrote a Memorial that tells us more about Romero’s land grant. On April 24, 1769, Gálvez gave Romero San Luis with "its house, church, tools, furnishings, lands, water, pastures from the arroyo of San Luis to that of Acheme including ten sheep, a ram, five little goats, six chickens, two roosters, and one quarter of the wild cattle."But Romero had to fulfill three conditions:

- To keep ready three horses that would be given to him for the Royal Post

- To fulfill the instructions of August 12

It appears that Lassépas was following the text of the original land grant

, which supplements the knowledge that Lassépas has given us.3 On Sept. 4, 1768 Gálvez had given Felipe Romero "a retired soldier of the company of the presidio" a grant in the San José del Cabo area, which he was now changing to San Luis with its furnishings and tools "and others that are in La Pasión." It adds to the list of animals a phrase that Lassépas apparently skipped over: "five lambs, ten goats, a billy goat," and one quarter of the wild horses and mules, as well as cattle of the land and mountains of San Luis and La Pasión, the rest of which are to be sent to Todos Santos.41772. Fray Juan Ramos de Lora talks about how difficult life was in early Rancho San Luis. Felipe Romero lives there

, but "with much necessity, scarcity and effort, is not able to maintain himself since, although he has the intention to sow, these sowings do not succeed, and he can’t raise cattle as he would like because of the damages and difficulties they experience. Therefore, he has been asking to pass to another place and abandon this one."5When it came to eating

, Baegert had written that the Spaniards knew nothing but corn, tortillas and tasajo, or beef jerky. This was certainly an exaggeration, but the traditional rancho saying, "Que un tasajo bien salado, no hay cosa mayor. Se bebe tinas de agua, que es tanto mejor," or "There is nothing better than a well-salted piece of jerky, after which you drink tubs of water - which is so much better!" was probably quite appropriate for rancho San Luis. Not surprisingly, Baegert has left us another version which goes: "Se bebe agua encima, que es horror," or "after which you drink tubs of water - what a horror!"6Lassépas goes on to describe the state of rancho San Luis in 1778 according to the manuscript of Padre Fray Gerónimo Salderillas:

"Half a fanega of tillable land, 60 feet of grapevines, 3 yokes of oxen, 68 fruit trees, 135 head of cattle, 15 horses, 15 mules, and 2 burros."7Unfortunately

, the rest of the history of the beginning of this rancho era in the Guaycura nation is nowhere near as complete, and is scattered in bits and pieces in a number of different documents from which we will try to reassemble it. The principle documents are:- The 1857 work of Lassépas with its compilation of old land titles. (L)

- Pablo Martínez

This somewhat meager harvest will be supplemented by the accounts of early travelers

, and the panorama of rancho life that Harry Crosby describes so engagingly in Last of the Californios.With the establishment of rancho San Luis a new era has begun. It is logical to imagine the repopulation of the now vacant lands of mission San Luis and Los Dolores would radiate out from here. But that is no more than a guess. Padre Visitador Ignacio Lizasoáin

’s 1762 itinerary through this area mentioned various stopping places like Jesús María, Quepo, San Hilario and Las Liebres, all of which are the names of ranches that exist to this day. Did they exist in the mission era, as well, and have mission workers who worked them for the missions, and had them serve as stations on the road? If they did, then it is possible that some of these people stayed on after the exile of the Guaycuras.In whatever way it took place

, rancho life in the Guaycura nation could not have been an easy affair, as we already witnessed in regard to the Romeros at San Luis. It will be played out against the stark background of the depletion of people and supplies drawn off Alta California, more epidemics, the further decline of the remaining missions which had been the very backbone that had held Jesuit California together, the failure of supplies to arrive from the mainland during different years - one chronicle states that in 1781, 1782, and 1783 little or no supplies were received; and in 1785, one ship is lost and "all classes were reduced to destitution,"8 - and finally the protracted Mexican revolution which deepened the isolation of Baja California. It was going to take independent and hardy men and women to pioneer these first ranchos, and create a self-sufficient way of life, dependent neither on outside supplies nor on government aid.

Simón Avilés

, SoldierSimón Avilés

, who served as a soldier before 1800, leaves us an idea of the spartan existence of the soldiers of that time, and the life of the first rancheros could hardly have been much better. "We lived in great discomfort in little, low houses with palm or earth roofs, very tiny and with cowhide doors for lack of boards; the entire furnishings of a house consisted of a bad cot or a wattle bed, a rough table and chairs made out of sticks crossed over two little adobe posts; at that time there wasn’t even one man in the whole country, with the exception of Don Manuel ‘Ozio, who could be called rich or moderately well off; we were entirely dependent upon the missions; since labors and adversities were common and the families in each mission very few, there was a good deal of brotherhood and union among them; they would give and lend each other everything, even their clothes; the same thing could be seen regarding those persons who came from the other missions; then there were no strangers, everyone knew each other and the majority were related by marriage or by blood. Only the missionary fathers kept their things for themselves and lived like strangers to our customs… we wore no underwear except shirts and shorts, and on the outside, pants and jackets made from cured deer hide; we wore our shoes next to our skin; we didn’t wear stockings or undershirts or cloaks in winter; then we wore some serapes from Durango over our clothes and that was our entire overcoat in the house or in the field; generally in the very cold seasons we warmed ourselves with fire; for that reason wood was never lacking in the house and was left in the middle of the rooms we lived in."9 "No wonder," Crosby comments, "that the people increasingly voted with their feet…"10 And as they began to create ranchos in the old Guaycura nation, knowledge of this area by the outside world may well have been fading away. Luis de Sales, for example, one of the Dominican missionaries who replaced the Franciscans and was stationed in the north of the peninsula, writing about 1790, mentions a port opposite the large island of Carmen called Tembabich. His English translator surmises that he is referring to Puerto Escondido, but can’t find a mention of Tembabich, which is our original Asembabichí. Even the history of the two missions is fast receding into oblivion. Los Dolores is conflated with the earlier visita of San Javier which carried the same name, and about San Luis, we are told, that its water supply failed and the Indians died, so from 1718 to 1768 there was hardly anyone there.11

José Longinos

, Naturalist1791-1792. José Longinos Martínez

, a naturalist from Spain, travels extensively in both Californias. His notes for our area read:Los Aripes to Los Reyes

, stopping place, water, 6 leaguesSalto de Los Reyes to La Vieja

, same, 5La Vieja to Guadalupe

, same, 4Guadalupe to San Hilario

, same, 6San Hilario to La Junta

, same, 5La Junta to Las Liebres

, same, 4Las Liebres to La Pasión

, suppressed mission, 3La Pasión to San Luis

, suppressed mission, 4San Luis to Cutoibo

, stopping place, water, 3Cutoibo to Tiguana

, same, 4Tiguana to Quereguana

, same, 4Quereguana to Quepo

, same, 5Quepo to Jesús y María

, same, 4Jesús y María to Andariche

, same, 4Andariche to El Pozo de Miguel

, same, 6He tells us that silica of different colors are to be found at La Junta.

"A great deal of petrified wood occurs in that vicinity, some of it half petrified, or partly petrified, and the rest agatized in the form of silica. At San Luis one finds jaspers and a large vein of (fossil) sea snails, as well as other petrified products of the sea, agatized and crystallized; at Cuytobo a variety of colored opaque quartz; at La Pasión hierro en talcoz, from which glass is made."12Longinos

’ route is very similar, if not identical, to the one followed by Lizasoáin 30 years before, and we can ask the same question: Were ranchos already established at these stopping places?1793. Jan. 11. Luis Romero

, given title for Santa Cruz, Comondú. (L251)Alejandro Mendoza

, San Luis, San Antonio. (L252)1797. Rosalía Castro is born at La Junta. (G575)

1799. August 16. Justo Morillo is born at Agua Escondida

, and dies there 94 years later.1811. Antonio Navarro

, received title for El Salto de los Reyes. (254)1813. Francisco Osuna

, title for Tiguana. (CB63)1814. Fernando de la Toba

, who had come to Monterey in Alta California, as a 16-year-old cadet from a noble family, (G35) appears on the scene as Governor, and is to go on and play an important role in the new rancho community of San Luis and La Pasión. (L213) In 1821 he is temporarily in charge of the government again (L203) and the following year, as commander of the troops of the southern jurisdiction, he swears allegiance to the newly independent Mexico, coerced by Chilean privateers who have attacked Todos Santos.1822. April 7. Felipe Avilez

, given title to La Matancita. (L223)Dec. 3. J.M. Murillo

, La Junta. (L223)1823. Feb. 13. Luis Sandoval

, title to Palo Verde. (L223) (PMA, II, 15, 99)Justo Álvarez

, title to El Coyote (CB43)April 1. Rafael Solorio

, title to El Portrero. (L224)1824. Dec. 24. Luis Álvarez

, title to El Mechudo. (L225)Justo Álvarez

, title to El Mechudo (CB43)1826. July 29. The Verdugo family has title to many ranches including El Sauce

, La Picota, Santo Tomás, Tiguana, El Potrero, Quepo. (L261)1828. Jan. 8. Ignacio Mayo receives title to Las Liebres Chiquitas. (L227)

Oct. 12. J.F. Flores

, title to Las Tarabillas. (L227)1829. Dec. 9. Fernando de la Toba is decommissioned as alférez at half pay. (PMA

, II, 23, 2866) Inventory of the archive of the Diputación. (PMA, II, 23, 2925)1830.

"In 1830, following the floods of the previous year which virtually destroyed Loreto, La Paz became the seat of territorial government and was thus revived as an important port. During the same period, Bahía Magdalena also became a center of activity for, following the establishment of Fort Ross in Alta California by the Russian-American Company in 1812, sea otter hunting was continuously extended southward as northern herds were depleted, and by the decade 1820-1830 Russian and Aleut hunters were operating in Bahía Magdalena under license from territorial governor José María Echeandía. Whaling by United States and British vessels replaced sea otter hunting in the region after the mid-1830s, and remained as its principal activity for almost forty years, although following the discovery of Laguna Ojo de Liebre by Charles Melville Scammon in 1858 the center of Pacific coast whaling moved to that area."131831. March 24. Dolores. Fernando de la Toba sends an inventory of his rural goods. (PMA

, II, 24b, 3157)1832. June 23. G. Avilez

, title to San Luis.1833. June 9. Fernando de la Toba makes a request to Juan José López for flour and corn in lieu of his pay. (PMA

, II, 27, 4187)October 18. Fernando de la Toba has received from Manuel Valenzuela 60 pesos against his overdue assets. (PMA

, II, 27, 4344)1834. March 5. Pablo de la Toba

, title to La Pasión. (L230)Apr. 12. Justo Murillo

, title to El Agua Escondida. (L230)May 1. Hermenegildo Lucero

, title to La Poza del Colorado. (L230)Camillo Morillo

, 1834-1887 at San Hilario (G)June 5. Raymundo Mayoral

, title to Santa Rosa. (L240)1837. Almost 50 years have passed since the founding of rancho San Luis

, and a new district is coalescing around it called Intermedios, i.e., the intermediate place located between La Paz and Comondú, and at some point it is divided into Intermedios Sur and Norte, close to or identical to the current boundary line between the modern municipio of La Paz and that of Comondú.

Cyprien Combier

, French MerchantAround this time the Frenchman Cyprien Combier who had sailed to La Paz to assemble a cargo of hides describes rancho life.

"Most of the people live on little ranchos, or farms. The ranchers’ occupations consist of riding horseback from early morn to overlook their herds, break horses and mules, slaughter the animals whose meat nourishes the family and serves in bartering, and, finally, in drying and preparing the meat, the hides and tallow that may be sold as excess. It is without doubt to this kind of life as much as to their origin that we must attribute their independent nature and a noble pride which strikes us at first sight. They are generally good, obliging and energetic, but their imperturbable dignity would never stoop to render a service which would have an appearance of domesticity or servitude. Their clothes consist of a cotton shirt, breeches, and an overcoat of deerskin tanned and prepared by themselves and decorated in different ways by the women… Women dress themselves properly and even with a certain coquetry. Preserving the complexion of their father race, they are, in general, much whiter than the men; their features are more delicate, their manners sweeter and more engaging. The cares of the household, the education of the little children, milking cows and making cheese are their exclusive functions. Their incomparable fecundity is due, without doubt, to a strong constitution maintained by coarse and simple but abundant food. It is not rare to find among them mothers in their forties having families of fifteen or even twenty children in good health; it is rare to see any of this age who have less than a dozen. One is surprised everywhere at the prodigious number of children who multiply in the thatched cottages and amid the brushwoods that surround them. This spectacle impresses the mind with an idea of the great growth of population, growth which manifests itself by the incessant establishment of new ranchos in places previously uninhabited."141837. Aug. 6 at Los Dolores. Fernando de la Toba

, interim prefect of the district, informs the authorities that he has named José Arce Justice of the Peace. (PMA, 7031)Sept. 6 at Los Dolores. Estanislao de la Toba writes to the Jefe Politico Luis del Castillo Negrete that he has received from Fernando de la Toba the post as judge of the ranchos between La Relumbrosa and the arroyo of La Pasión. (PMA, 7078)

Oct. 12 at Los Dolores. Estanislao de la Toba

, Justice of the Peace of the ranchos of Intermedios, writes to the authorities that if anyone wants to know about Manuel Valenzuela and José María Veliz they are citizens of this jurisdiction. (PMA, 7125)Nov. 10 at Los Dolores. Vicente Romero becomes the substitute Justice of the Peace of the ranches between La Relumbrosa and El arroyo de la Pasión. (PMA

, 7168)Dec. 8 at Los Dolores. Fernando de la Toba sends to the authorities a copy of the form he will send to the Justices of the Peace in order that they can put down the statistics of their respective jurisdictions. (PMA

, 7226)1839. June 5. Raymundo Mayoral

, title to Santa Rosa. (L240)1841. Jan. 15. Fr. Gabriel Gonzalez reports to Governor Negrete there are six priests in Baja. The nearest to San Luis: José Antonio Mosquecho

, a Dominican who arrived in 1835 and is in charge of San Antonio, and Vicente Soto Major, a Mercedarian, who arrived in 1836 stationed in Loreto.15June 23. Half a cattle grant at Sauzoso for Juan José Cota

, and on June 26 half a cattle grant to Francisco Betancourt.161842. Aug. 1. A cattle ranch at Los Achemes

, Carmen de la Toba.17José María Vélez

, title to Jesús María. (L260)The French traveler M. Duflot de Mofras gives the population of La Paz as 400

, while the mission of Comundú has 81.181844. March 26. Hacienda de Los Dolores. Ramon de la Toba

, the principle Justice of the Peace of Intermedio, writes to the authorities in Loreto about Urbano Rodríguez because of the claim made against him by Encarnación Romero. (PMA, II, V42, L3, 1FF, 061)April 20. Ramon de la Toba writes concerning another case involving Ramon Talamantes. (PMA

, II, V42, L4, 1FF, 084)Sept. 10. Ramon de la Toba writes concerning the collection of taxes and the problems arising because the landowners do not have titles. (PMA

, II, V42bis, L9, 1FF, 246)1845. Jan. 15. Cornelio Espinosa

, title to El arroyo de la Pasión. (L234)1846. Nov. 22. Francisco Sosa y Silva marries Gertrudis Baldenegro. He is a native of the Azores.

1847. Feb. 16 at San Luis. Vicente Romero

, the judge of Intermedios writes to the authorities concerning a land dispute involving Pablo Álvarez. (PMA, II, V44, L2, 1FF, 028)W.C.S. Smith

, American ‘49er1849. Jan. 5. W.C.S. Smith left New York to travel to the California gold rush via Veracruz

, San Blas and Mazatlán, but he and some of his companions, angered over the conditions on the ship, decided to go overland from San José del Cabo to Alta California. Unfortunately, they appear to have had little prior experience in this kind of venture, and even less knowledge of what lay ahead. They went to Todos Santos and then followed the coast northward, when the road turned inland somewhere, probably around the arroyo of Guadalupe. Their animals were failing fast, and the first horse had almost given out, and another had run off. Then luck intervened. And it is our luck, too, for they give us a portrait of ranch life in Intermedios. One of their members came in from the hunt with what Smith describes as an Indian who told them of a ranch a few miles away. "We have found here a gentlemanly Portuguese, the son-in-law of the proprietor. He speaks English."19 He tells them had they continued along the coast they would have found nothing ahead of them for many, many miles.April 18.

"Laid by all day at the rancho, buying horses and making provisions for prosecuting our journey. People very kind. The Portuguese very intelligent. He has a fine vineyard and fruit trees in a valley back in the mountains. My new horse is a beauty, but wild like the Californians themselves. Much interested by their wonderful performances with the Lasso. This seems a good specimen of a California ranch. The old proprietor is as one of the ancient Patriarchs. They are a better people than the Mexicans. Now to my blankets. They have spread ox hides on the ground for us to lie upon, quite a mark of civility towards us. This place is called the "Rancho Colorado" from the river of that name on the bank of which it stands. The house is a long low rambling concern, built of reeds and brush interwoven. The roofs of weeds and flags. One half of one side open. A ground floor. In the corner of the room is a clay furnace for cooking. The river is dry now except for a large and deep pond of several acres which is the water supply for the establishment. For drinking purposes there are under the shed two large vessels of porous earthenware kept filled with water, and in which it becomes very cool. The Portuguese told us that years sometimes passed without the river flowing; but occasionally it was furious, which was apparent from the immense channel and marks of destruction. Such is the character of most of the streams in the Abajo. At the time we passed there had been scarcely any rain for five years. The people live almost entirely upon beef cooked every way except any mode we were accustomed to, but they never fail to add chili pepper enough to bring tears from the eyes of a dried codfish. "We bought a steer and had the man dress and jerk the meat for us. Theyroasted the head

, hair, horns, and all with hot stones in a hole in the ground. They politely invited us to share. We were not fastidious and laid hold. We found it perfectly delicious. They were much interested in our revolvers. Had never before seen such a weapon. But what they most coveted was tobacco. Our stock of that was low and Nye and I were smokers, yet we divided with them. Afterwards we smoked willow bark ourselves. The old proprietor was years ago a leading politician in Mexico. Was exiled to this place by the Emperor Iturbide. He had here an immense tract of desert land and about 2,000 head of cattle and horses, his sole wealth. We learned from Francisco, the Portuguese, that the journey before us was a serious affair. He gave us much advice which was of timely benefit. He told us of a party who from lack of precaution had not long before perished on the same route. Under his supervision, we were furnished with a number of leather water bottles which they all charged us to fill at every opportunity. Told us to throw away our Mexican bridles and huge steel bits and ride our horses with hackamores (head halters). Also provided a stock of dried beef and "pinole" (wheat ground by hand on a tortilla stone.)"20They leave the next day with a guide to San Luis

, and reach it at 12 o’clock on the 20th, expecting to find "at least a small village, but it is nothing but a deserted old Jesuit mission, in ruins. It stands solitary in the midst of desolation." They find "an old decrepit Indian"21 who shows them some paintings of the Madonna and saints in good condition, but has nothing to offer by the way of food until they press him about the matter. For the next three days they struggle onward, not seeing a single person. Finally on the 24th they find a small ranch in the morning, but lose the trail and climb up a steep mountain. Later they discover they have strayed from the coast trail, and now are on the mountain road. On the 25th they arrive at what must have been, by their description, San Javier. All this tribulation, and they have yet to enter the great Vizcaíno desert. They are to survive, and finally arrive at San Diego, grateful to still be alive.Rancho Colorado was somewhere in the vicinity of El Estero near the Pacific coast

, and endured until at least the early 1920s when it is found on a map drawn by Carl Beal based on information he compiled in 1920-21.22 The question of the identity of Francisco the Portuguese leaves us with two choices: Francisco Betancourt or Francisco Sosa y Silva.August 31 at Santa Cruz. Francisco Betancourt writes to the Jefe Politico

, Rafael Espinoza, about the titles to ex-mision San Luis Gonzaga in 1769 and 1846 of Vicente Romero. (PMA, II, V45, L8, 1FF, 249)The same day he writes about the revalidation of the title of Vicento Romero according to the conditions of May 20

, 1776. (PMA, II, V45, L8, 1FF, 251) He also writes about the grant to San Luis made by José Gálvez to Felipe Romero.Sept. 3. Francisco Betancourt writes to the authorities concerning the soldier Guadalupe Manrique and some steers. (PMA

, II, V45bis, L9, 1FF, 264)